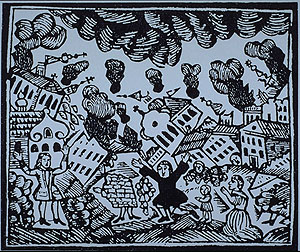

In the wake of two devastating earthquakes, we are again witnessing echoes of longstanding debates over “theodicy,” or the effort to justify the existence of a just and loving God in the face of the existence of suffering and even evil (Theos=God; Dike=Justice). These debates are hardly new – current debates remarkably echo arguments that took place some 350 years ago following the devastating Lisbon Earthquake of 1755.

In the wake of two devastating earthquakes, we are again witnessing echoes of longstanding debates over “theodicy,” or the effort to justify the existence of a just and loving God in the face of the existence of suffering and even evil (Theos=God; Dike=Justice). These debates are hardly new – current debates remarkably echo arguments that took place some 350 years ago following the devastating Lisbon Earthquake of 1755.

One reaction against “theodicy” – the effort to “justify God’s ways to man” – in the face of such horrific devastation was (and remains) two-fold. First, there is a rejection of the idea that there is any “meaning” to such an event – and rather, the conclusion that the earth and nature is capricious and undiscriminating in its bestowal of life and death. Second, in the face of belief in this very “meaninglessness” of the world, there are demands and efforts for active human intervention to impose meaning, and particularly, to pursue ever-greater arrangements of justice. The modern scientific project was the result – arising in significant part in response to the Lisbon earthquake – allowing humanity increasingly to control the arbitrariness of nature’s actions upon humanity.

Responses to the recent earthquakes in Haiti and Chile have hauntingly echoed the reactions of the world’s leading philosophers some 350 years ago following the Lisbon earthquake. While this fact has been noted by some prominent commentators, what has gone largely unrecognized is that there is one important difference today: we live in the wake of several centuries of mixed record of scientific achievement.

The confidence of many in the late-18th century over the ability of science to master the arbitrary actions of nature is today complicated by our own experience with the deleterious consequences of that very mastery. Even as we respond with the hopes that modern seismology will give us the tools to avoid such catastrophes, and that modern social science will permit sufficient worldwide wealth so that the poverty of Haitains will not be a major contributing factor to the devastation, there is a simultaneous recognition that this project of mastery has given rise to a different kind of devastation – one largely created by humans in the form of environmental degradation.

The problem is, we rarely connect these two observations.

While theodicy has existed as a form of human inquiry at least since Cain killed Abel in response to God’s otherwise inexplicable preference for his brother’s sacrifice, the “science” of theodicy is often traced back to the philosopher Leibniz. It was Leibniz who offered the first articulation of philosophical optimism, expressed pithily in the phrase that “we live in the best of all possible worlds,” which summarizes Leibniz’s somewhat heterodox view that God chose from among a near infinite number of possible universes, and chose ours as the best one worthy of creation. While not perfect, overall, it was pretty good.

The Lisbon earthquake shattered this view. In the reactions it provoked, one sees especially the origins of many of today’s stances in regards to science, religion, and nature.

For some, the earthquake was evidence of God’s wrath – the theodicy in which we can interpret with certainty the will of God in the events of the world. The reactionary author Joseph DeMaistre (responding to Candide) argued that the earthquake was in fact a great good, because its residents surely deserved to be punished (and, he argued further, the innocent deserved to be delivered from the iniquity of that place). This was the opposite of Leibniz – all is good, because all is bad. We can see echoes to Maistre’s conservative critique in the reaction of Pat Robertson to the Haiti earthquake – the destruction was divine recompense for an evil committed by the Haitians (just as the attacks of 9/11 were deserved because of the iniquity of modern America).

Then there was the response of Voltaire, long suspicious of clericalism and superstition, who saw in the Lisbon quake evidence of a capricious and even cruel world. In his famous novel Candide (Candide, ou l’Optimisme), Leibniz’s phrase becomes ultimately an idiotic mantra contradicted by the reality that the earth is not the best of all possible worlds. That novel describes the eventual disillusionment of Candide from the philosophic optimism of his teacher, Dr. Pangloss, a disillusionment that is completed by his confrontation with the devastating earthquake of Lisbon. Voltaire’s recommendation (through the words of his character, Candide), was to “cultivate your own garden” – that is, to take care as best one could what was under your own control, recognizing that there was no final justice or meaning in the universe. One heard echoes to this view recently in the analysis of James Wood (who also revisited the reactions to the Lisbon Quake in his essay. Wood concluded his article by condemning the Maistre/Robertson view (as would Voltaire) while ending with a plaintive, existentialist plaint: “For either God is punitive and interventionist (the Robertson view), or as capricious as nature and so absent as to be effectively nonexistent (the Obama view). Unfortunately, the Bible, which frequently uses God’s power over earth and seas as the sign of his majesty and intervening power, supports the first view; and the history of humanity’s lonely suffering decisively suggests the second.”

Yet, it is this view – the disillusionment with interpretations that God’s will could be known one way or the other (understanding either suffering as the result of retribution or the consequence of “the best of all possible worlds”) that opened the door to the flowering of the Enlightenment, and particularly the belief that with the rejection of outdated theological categories, a new kind of understanding and even capacity to confront and overcome evil and suffering might be possible.

Notably, Immanuel Kant (Enlightenment’s prophet) also sought to comprehend the devastation of the Lisbon quake, writing three texts on the event. His response was to develop a geologic theory of why the earthquake took place, surmising that the earth’s instability arose due to the shifting of large underground caverns filled with hot gases. According to the 20th-century philosopher Walter Benjamin, Kant’s analysis – while long-since discarded – “probably represents the beginnings of scientific geography in Germany. And certainly, the beginnings of seismology.” Shortly after the Haiti earthquake, there were simultaneous lamentations over the still-imperfect science of seismology – at least insofar as its predictive powers were concerned – alongside articles that praised the ongoing and discernible advances in the science. According to Simon Winchester, while the science of earthquake prediction is far from perfect, “The branch of seismology that deals with prediction is undoubtedly in a slightly better place than it was half a decade ago.” And that fact, he writes, should provide “a faint glimmer of hope.”

In the wake of such devastation, nature was increasingly understood as an arbitrary and often cruel force, one devoid of meaning. Either there was no God, or God was either “absent” (as Wood suggests) or cruel, but in either event, humanity was largely on its own to improve its own condition. Drawing on thinkers like Francis Bacon and other architects of modern science, Enlightenment thinkers pushed forward a new kind of science – one that would seek the mastery at least of the effects of nature (if not the causes of various devastations), whether in the forms of medicine, weather prediction, flood control, agricultural science, chemical engineering, and so on. A revolution in human life in part can trace its roots to that earthquake in 1755.

What is striking about the contemporary echoes to these arguments is a changed contemporary context. We are witnessing not only echoes, but widespread embrace, of another reaction to the Lisbon earthquake – that of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Rousseau – in a letter to Voltaire – argued that the earthquake revealed not the existence of divine retribution nor the need for Enlightenment solutions, but the evils of “progress.” Long suspicious of the arguments of Enlightenment colleagues, he argued that it was the concentration of humanity in to compressed living space – versions of tenements and high-rises – that led to the devastation of what otherwise would have been merely a curiosity and perhaps inconvenience to healthier, more primitive societies. He argued that humans should not live in unnatural ways, in contradiction to nature.

Rousseau’s arguments have made a significant comeback: we live today with the existence of both an embrace of scientific aims of progress and a deeply pervasive adoration of nature, along with a deep suspicion of the advances of science and technology.

There is no better evidence of this latter view than the remarkable popularity of the movie “Avatar.”

“Avatar” portrays the simple humanoids that Rousseau praised in his letter to Voltaire. What is striking about that movie is that nature is portrayed as almost entirely benevolent. Yes, at the beginning of the movie, Jake Sully (newly metamorphosed into his Avatar) is attacked by some savage animals. However, evidently the Na’vi live in perfect harmony with the natural world, and even those creatures that once attacked Sully become allies of the Na’vi in the culminating battle scene. There is a complete harmony between humanoids and nature, reflected in their ability to “connect” fully with the natural world, their intuitive capacity to discern the deeper connections between all natural beings. The perpetrator of evil in the world is not now “nature” – but humans, and especially those humans who employ science and technology in the effort to master nature (particularly the extraction of a natural resource that we are to understand to be the Pandoran version of petroleum). Thus, it is the very activity that has allowed extensive human conquest of the natural world (and thus, the capacity to govern or eliminate its arbitrary motions) – science – that now threatens the perceived harmony of nature.

For moderns, nature and science are simultaneously – and exclusively – the respective source of evil and good. Indeed, I am willing to wager that people who enjoyed the defeat of rapacious humans in “Avatar” also regularly condemn the capriciousness of the earth. I would further point out that this is a contradiction particularly keen on the American political Left, which simultaneously insists upon the merits and necessity of scientific advancement, and embraces a Rousseauian environmentalism that condemns science and technology out the other side of their mouths. Moderns on the whole, and the Left in particular, compartmentalize the two evaluations.

Our age calls for a better theodicy and a better understanding of nature – one that (to start in the realm of nature) recognizes that nature is both a source of goodness and pain, of life and death. These two cannot be un-extricated. It needs, too, a more supple Augustinian recognition of our own ignorance – whether in claiming to understand God’s will (a la Robertson) or claiming to discern His total absence (a la Wood). We need to embrace not these various claims to knowledge, but rather (to cite an essential essay by Wendell Berry), the “way of ignorance.” The “way of ignorance,” he writes, is “the way of faith” and the path to the acceptance of “the wisdom of humility.” In part, it prevents us from seeing the world through the lens of pride – the pride of knowing with certainty that nature is either evil or good, or that science is either good or evil. It can help us to stop living the contradiction of modernity, and begin to make judgments, rather than rest in the faith of our contradictory certainties.

You should take a look at Daniel Mendelsohn’s review of Avatar in the current issue of the New York Review of Books. http://www.nybooks.com/articles/23726

He suggests that the ambivalence toward technology, science, and nature that you find common to left environmentalism is also quite evident in Avatar, where the natives are not merely in tune with nature but can actually link up with it as if they were connecting with a huge computer/information network. According to Mendelsohn, the Na’vi aren’t noble savages at all, but high-tech computer geeks, or at least a hyper-athletic version of such (and of course, they were created with all the latest souped-up 3D imax techno-gadgets that Mr. Cameron could find).

Patrick,

What do you make of the advocacy of some on the environmental left for “green jobs”? Is this not a way to have your cake and eat it, too? We can be kind to nature while also creating jobs and wealth through green technology. This strikes me as being distinct from a left that “insists upon the merits and necessity of scientific advancement, and embraces a Rousseauian environmentalism that condemns science and technology out the other side of their mouths.” I mean, Na’vi don’t drive Prius’s, but many self-righteous leftists do.

Pat, I liked the way you showed linkage between knowledge and pride, a point that grounds my own thoughts of gnosticism and its optimistic cousin, hermeticism, in their age old effort to conjure a magical reality sans God.

However, there are “political” sciences e.g. “politically correct science,” clearly illustrated in the recent revelations that certain climate data was falsified by radical leftists to justify a lie, which suggests that scientific information will have to be closely monitored.

It is the disturbing fact of conflicting evidence that makes theodicy necessary. And while it is true that in many cases we humans are the cause, or at least a contributing factor, in our own disasters (cutting corners by using substandard cement in construction, for example, or insisting on living in areas prone to flooding, the catastrophe of war, etc).

But sometimes, things happen, seemingly randomly and most certainly tragically – routine surgery that goes inexplicably wrong, or a drought that wipes out local subsistence agriculture for three years leading to massive famine. God gets the blame when we are faced with circumstances we cannot explain. Dissonance occurs when our image of God is undermined by our experience of reality. We get entangled in complex discussions of the relative boundaries of human freedom and divine sovereignty, and we are uncomfortable with the implications of every attempted solution.

For those who understand the Christian Scriptures as revelation, there is much that the Christian Trinity has revealed about himself and his ways. But there is also still much that is left unexplained. Evil is one such issue, as is God’s apparently hands-off treatment of it, at least in our limited experience. Somehow, the equation of God’s risk in creating creatures with the capacity to love (which meant creating creatures with the capacity to choose not to love), combined with the actuality of our choices, multiplied by the implications and consequences of those choices reverberating across countless relationships, including, most seriously, brokenness, alienation and death itself, somehow all this goes a long way towards comprehending the slow-motion train wreck we all seem to be participating in. But it also goes a long way towards explaining why incarnation, cross and resurrection, reconciliation and the restoration of the ability to love make up God’s unexpected answer to our plight.

Those who wish to follow Job’s wife’s advice to curse God and die have the harder task of explaining why God would choose to take on our curse and undertake death itself – his own theodicy, as it were. Could it be that there is something bigger going on than we can fathom?

Well said William.

I do think that the story of Cain and Abel has been misread by the author as an “inexplicable preference.” A quick consultation with any respectable commentary from a Biblical commentary would reveal a wealth of solid interpretation. I’ll cut to the chase- it was a matter of the heart. A charismatic singer from the 80s once sang:

“To obey is better than sacrifice

I don’t need your money

I want your life.”

Far and away the best book on theodicy I’ve ever read is David Bentley Hart’s ‘The Doors of the Sea,’ subtitled ‘Where Was God in the Tsunami?’ Hart looks at Voltaire’s response to the Lisbon earthquake and sees an attack not on the God of Christianity but the false God of a rosy deism. The real challenge to the goodness of the Christian God is found, according to Hart, in Ivan Karamazov’s protests against the unwarranted suffering of innocent children; and Hart believes that Dostoevsky, through Alyosha and Fr. Zossima, answers Ivan’s challenge.

I’m of the opinion that attempting to discuss theodicy without reference to it is akin to discussing ethics without reference to Alasdair MacIntyre.

Rob is quite right to bring up Brothers Karamazov; the episode in question relates directly to Dr. Deneen’s application of “the way of ignorance.”

In one particularly striking passage, Ivan compares the thought of a mother forgiving her child’s murderer to non-Euclidean geometry in which parallel lines do in fact eventually meet — he cannot conceive or understand either occurrence, and thus refuses to accept them.

The quest for easy answers continues apace. Man, this self appointed humane being is still but Potency. Until he stops his relentless banging and breaking of bones on this apodictic earth, he will remain simply the greatest contender on our planet of light and love. We strive for the truth of Being but awash in our materialism, we remain almost wholly distracted from the Actus Purus.

Perhaps potency is enough for us. If it is, count on fear, dread, lust and revenge continuing their dynamic reign. There will always be another hurricane , earthquake, volcano or war. Their aftermath reminds us of the trail into Being we forsake at the altar of amusements called Potency.

Needles to say, Dr. Pangloss will be there to smile and tell us to soldier on cheerfully while Mephisto lurks in the debris-laden background, harvesting our industrial output of strivers. Meanwhile, the pridefully righteous will tut-tut in chorus, like the click-clacking of dung beetles in the duff, rolling little balls of shit as if their life depended upon it.

Still, this attempt at Being deal is better than a kick in the head, which it sometimes is. Anybody with the bad form to accuse victims of any tragedy as deserving their fate, particularly when said accusation is rendered from the comfort of a televised confessional….well, they should keep an eye peeled for incoming.

Fiat Termini & shifting

I am very much disappointed to hear that Fiat and many other companies are shifting their production centres from Italy or their home ground. As everybody of us knows that, it will create a community of unoccupied peoples and poverty in the society. Here the main issue is that, the companies are shifting their production centres to other nations, only for increase their profits. On those nations these companies are getting only the manpower at a low coast. All other cost of productions is almost same with their home land. So only for this reason (availability of labours at a low coast) they are shifting their production plants and creating a community of non working peoples and poverty in their home lands. But here the interesting thing is that, these all companies are looking to market their products mainly in the home land. For this they are spending a good amount as the shipping and other transportation. They want to market their product, where they are not interest to work. I am trying to say to these companies that, if the peoples over the country where you want to market your product, and are not having a proper job and falling into poverty, how you can market your product or how they can buy your product? So don’t try to look only your pocket, try to look after the peoples behind you. If the peoples over a country cautiously lost their jobs the crisis will be remain as the same……………

The proof of God’s existence comes in the everyday miracles of people’s survival of such tragedies of natures and their response to them to aid the suffering and in spite of death such persons receive eternal life. If we do God’s will in the face of such tragedies, then God lives in all of us.

[…] lots of good stuff at Front Porch Republic but here are couple of posts “WhyUs God?” by Patrick Deenen and “It’s the Land, Stupid!” by D.W Sabin. | | | | […]

Here’s again some history for the consideration of those whose minds and hearts tend toward abstractions. The worst earthquake we actually know about–that is, in terms of its violence and extent, not necessarily in loss of life (Haiti gets that one)–was the New Madrid abruption of 1811, which actually caused the Mississippi River to run backwards. The biggest was the San Francisco quake of 1906, which was probably a nine or better, and extended from Oregon to Los Angeles. The reason to bring up this history is that the Saint Louis University (where I taught from 1967-75) seismographic center was founded by Jesuits in 1910 to look hard at exactly the difficulties Patrick brings up. Fr. James B. Macelwane not only founded, but was the leader in this research until his death in 1956. There is not only no disjunction between religion and science, there is a compatibility that gives science its only meaning in relation to the Created Order.

Typo: 1755 is ~250 years ago, not 350.

It would seem that Rousseau would also say, “Don’t build your village under a volcano and complain to God when your village is destroyed by lava.” People sometimes choose to live in harm’s way. Neither the earth nor God would be necessarily responsible for the outcome in this case.

Nearly everything presented here has something to recommend it. Any approach to theodicy has to recognize that “My ways are not your ways, saith the Lord.” So, Pat Robertson hasn’t a clue, and neither has anyone else, as far as getting to a definite answer.

We should, however, factor in free will. We have free will. We bear the costs of our own decisions. God may, for his own reasons, or out of sheer love for us curious hybrids (cf. C.S. Lewis), intervene to save us from the consequences of our own, or our neighbors’ decisions, or might not. Does nature have free will? Probably not in any sense of conscious, intelligent, self-aware, directed, will, but nature has not been carefully arranged to that we never get hurt, or everything always goes our way. If it did, our free will would be of little significance.

Rousseau has a point about our living in ways that invite greater disaster, e.g. crowding into large cities and tall buildings. How extensive would the damage from planes being crashed on 9.11.2001 have been if they crashed into an extensive tracts of bungalows, let along isolated rural farmsteads? This is where I really think overpopulation is a significant consideration. Maybe our technology and intensive agriculture can manage to support increased population, but how much more vulnerable do we make ourselves to tsunamis and earthquakes, hurricanes and tornadoes, in the process? There are other issues about what we are living for when we take that course.

In the end, I simply suggest that if things are going well, thank God, and if they are not, obviously things are not in perfect order with the way God would have things be. Nature is not perfect, we are not perfect, in some fumbling sense that even we don’t perfectly understand, we are supposed to perfect ourselves, and our world. “REPLENISH the earth and subdue it…”

A little late to this article, I know. Theodicy arguments always catch my eye. Please allow me to posit a few ideas.

The tension of a tragedy seems to be, “God where are you? God, how could you?” My argument comes from the a priori belief in Christian theology. I believe the idea of God leaving things to chance is not the Christian belief. God DOES ALLOW seemingly bad things to happen. “Allow” is not the correct word. God “controls and uses” bad things, is probably closer to the truth of the matter. Not only bad things, but evil as well.

I think I can get here from Biblical example, but I want to skip the heavy-lifting of this for now. In brief, have a look at Job. God makes no apologies to Job for submitting his servant Job to a “prove it” dual between Him and Satan. In the beginning God and Satan are having dialog. Imagine that.

Moving on. OK, so what happens in a tragedy? Many horrible things, but often times mass amounts of people die, or suffer horribly. As I make the following point, I hope I do not trivialize the death of anybody, but my point is, do not ALL OF US die?

I’ve only been close to a couple of deaths in my lifetime. Family members. It’s sad and it’s disturbing to a very deep spot inside you, but death typically has much pain associated with it. I remember the nurse making sure the morphine-drip was cranked-up on the day of my mother’s passing.

How many times have you heard someone say, “At least they went quickly.” The point being, at least they did not struggle with excessive pain.

Great for them. What about the people we know who have struggled for years on end with a cancer battle? Perhaps then the issue is not so much early death, but PAIN.

I’m with the perspective that whether a falling roof cracks my head open, I drown in the ocean, or I yield to cancer, my death will probably be painful.

So God designed the world with pain as part of man’s condition. It seems to be a part of the condition of all the animals too.

Death will never be easy to watch. And observing it on a mass scale, as in Haiti, or the south Pacific, does have a different difficulty about it. But on the level of the individual who lost his life that day, it must be accepted that his day to die, was simply THAT day.

What is it about man that we feel something quite significant about constructing unique perspectives that stand as obstacles between us and God?

Questions such as: “There’s so much pain and suffering in the world, where is God?” Seems like a thoughtful enough question. “You get me through this one, God, and I will have an easier time following you.”

Do we WORK AT such questions? Or is it rather that once erected, they serve us well as our conundrum for years on end?

What’s the nature of what we classify as “pain and suffering?” There’s much that can be said about this. I think we will find that man inflicts MORE pain and suffering upon one another, than God’s natural disasters ever do.

If we must have a reason for God’s natural disasters, how about this one. In the face of disaster, it suddenly becomes very clear that those that are able, need to tend to those in need, and we need to do it now.

It’s quite easy to loose sight of loving and caring for one another when the fridge is full and the game is on. Not that love and care does not happen in these moments either, but I think you get my point.

If you are to this point. Thanks for reading my post. I look forward to learning more from the thoughtful words of this blog.

Thinking this past week about a world without pain. What a place that would be. Fit’s with our naive attempts to grasp Heaven. Now consider for a moment brain tumors. From what I understand, often times there are no symptoms until the tumor(s) are quite large. Interesting. In other words, there is no PAIN until the tumor is quite large. I guess we could say that in a perfect world there is no tumors, disease, death, or pain. This is absolutely foreign to anything in the human experience we seem to be living. The construct becomes quite alien. Another inquiry, which is more “realistic” and valuable, is to look at pain and discomfort as a flashing red light. It’s a warning signal, a attention grabber. Pain can shake you like nothing else. I guess this pushes the inquiry toward a view of pain that assumes that we can change things. Sometimes we can’t, or sometimes it’s not apparent what we can do, or perhaps what we CAN DO is only a small step, and the pain remains.

I don’t have all the answers, but to me, any discussion about theodicy is a discussion about pain, and God’s intentions and use of pain.

Theodicy. There is that question, that many ask “why did God do this or allow this terrible thing to happen”?

I can understand this question being asked by non-believers of Judeo-Christian theology. But I think believers should already know the answer to this question. The fact is, God put creation in motion. The fact that he gave us humans free-will proves that he has deferred a lot of control and power to mankind. He is not a puppet-master. He did not make us and nature so flawed that he has to constantly nudge us along. We are his handy-work, and although he purposely didn’t make us perfect, he did give us a remarkable brain, made us in his image, and planted a craving for him; at least in his elected. To live is Christ, to die is Gain. So if believers truly believe that, then why are they so scared of death? Hurt from death? Do all they can to bypass death? Could it be that the dirty secret answer is that most beleivers really are not true believers? If you truly believe in an afterlife, you would welcome death. Not by your own hand, but in a natural way. So what about cancer and other terminal diseases? What about pain? What about 9/11? How does God fit into those terrible things? I think these things are the consequences of what God placed in motion eons ago, AND acts of man, things men have done, good, bad, everything in between. Man discovered that inhaling burnt tobbacco makes him feel “good”, so is lung cancer God’s purpose? Sure he could cause burnt tobbacco to be harmless to us humans. But he chose not to. He allows us to build our homes in the less than ideal places, and watches as nature destroys those homes. Again, he create the universe, got the earth spinning, and then stepped back and watches us. Sure he may chose to intervene now and again, but I think mostly he lets it all run it’s course, according to his plan. He is no puppeteer, to be sure. He wants us to use our free will to want him back, to accept his invitation. He is not one to force this from us. So the next time a tsunami wipes out an innocent population, count them the lucky ones. They get into the afterlife before you. And hopefully on the side of heaven. So if you really believe that he conquered death on the cross, then you should not ask such questions because you should already know the answer.

Comments are closed.