Washington, DC

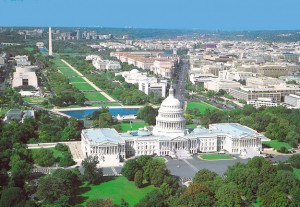

I’ve been spending my semester in exile in our nation’s capital. My apartment is in Arlington, on a ridge overlooking the city. From that spot I have a clear view of the Pentagon, the Capitol dome, the Washington monument, the Lincoln memorial, the Smithsonian, office buildings, and off to the north the National Cathedral: a panorama of the temples of democracy.

When I told my compatriots in West Michigan I would be spending the spring in Washington DC, the typical, and indicative, response I got was “Could you fix it while you’re there?” The problem is not that I lack the power to fix it. The problem is that Washington can’t be fixed.

A reader of the Christian scripture must be struck by the extensive role played by the city, whether as the object of eschatological fulfillment, or the place of sin and corruption. In the main, the narrative arc of the Scripture moves from the garden to the city. There are at least a couple of reasons for this. First, the city represents the end point of the command to fill and subdue the earth; it is the place of civilization, as the name itself suggests. Despite our suspicions of cities – Benjamin Rush compared them to “abscesses on the human body” which served as “reservoirs of all the impurities of a community” – cities nonetheless are hothouses of civilizational activity: art, science, procreation, law, and so forth.

Second, cities, as Pierre Manent has pointed out, are both the form and symbol of integrated social relationships. We are social creatures, and cities are the place where most of us live. As such they are the normal context in which we would deliberate on the nature of integrated relationships, the apogee of which is the church itself as a universal polis. The Holy City, as portrayed in Scripture, is a place of great wealth and splendor, not a place of dirt roads and impoverished denizens.

So central was the city to the early Church’s understanding of the Christian life that it became the dominant metaphor in St. Augustine’s reflexive understanding of Christian living. We are, in our essence and being, citizens of a city, and all cities are oriented toward a future and toward the binding effects of shared loves. They are not just what we hold in common; they are the common.

But Augustine’s monumental meditation, with its emphasis on two exclusive and competing cities, sharpens the already developed Scriptural disjunction between life in this world and membership in the eternal city. Temporal cities were no longer the ordering of life according to what was common; rather, invitation into Christ’s kingdom introduced confusion into how we were to live. The writer of Hebrews reminds us that “we have not here an abiding city, but we seek after the city which is to come.” But we are embodied in the here and now, and Christianity is an embodied religion.

Which city are we to inhabit? How do we adjudicate the disparate demands? Manent, again, argues that we might think of modernity itself as an attempt to resolve this paradox by eliding the referential disorder created by Christianity: the disjunction between what we say and what we do, between what we will and what we ought, and between competing authorities. As Max Weber wrote: “He who seeks the salvation of the soul, of his own and of others, should not seek it along the avenue of politics, for the quite different tasks of politics can only be solved by violence. The genius or demon of politics lives in an inner tension with the god of love, as well as with the Christian God as expressed by the church. This tension can at any time lead to an irreconcilable conflict. Men knew this even in the times of church rule.” In order for the speech of the city to be authoritative the secular city had to develop a speech of its own, and it found this in society itself.

Bertrand de Jouvenel asserts in his On Power that in becoming a “representative” of society, the state was able to monopolize authority, and thus able to combine the things Christianity had rent asunder. Practically, this meant the development of a civil religion, secular administration, unified sovereignty, and representative government.

De Jouvenel believes that power used the idea of popular sovereignty as a way to obliterate operative limits (or “makeweights”) – estates, the Church, nobility, and divine law – and emerge reconstituted in an absolute form. In that sense, the mechanisms of representation can do little to slow power’s advance. The instruments of rule are parasitic on society and gradually absorb social authority into themselves; at their apogee in the development of a powerful capital city which, in its late stages, becomes defined by plutocracy, Caesarism, and imperialism. “The City of Command” is the “place of dominion, the hearth of justice, the haven of the ambitious.”

A saving grace for America, Tocqueville believed, was the absence of a strong capital city. “To subject the provinces to the metropolis,” he wrote, “is therefore to place the destiny of the empire not only in the hands of a portion of the community, which is unjust, but in the hands of a populace carrying out its own impulses, which is very dangerous. The preponderance of capital cities is therefore a serious injury to the representative system; and it exposes modern republics to the same defect as the republics of antiquity, which all perished from not having known this system.”

Likewise, Oswald Spengler believed that the idea of progress, that civilizations would follow and build on one another towards a kind of inner-worldly fulfillment, was a uniquely Western and prejudicial symbolization. When looked at properly, Spengler claimed, the West appeared as just one more civilization among others. Thinking about civilization organically rather than progressively or mechanistically, Spengler could observe variations in the basic life-forms of civilizations, which could then be compared analogically.

The decline phase of civilization, which the West had now entered, and whose mantle had shifted to America, brings with it Caesarism and imperialism. These result from two related processes. The first involves the development of the civilizational phase itself. The free, culture-generating life of town and village, dominated by folkways and mutual life-formation, is gradually replaced by great cities that twist and distort culture, replacing meaning-giving forms of life with irony, cynicism, money, and cosmopolitanism.

One of the interesting parts of Spengler’s presentation is that cities only have the appearance of being creative, artistic places. The true creativity, he argues, takes place in small towns and villages where individuals shape artistic expression in a communally nurturing fashion. Artists in the cities are bohemian: disaffected, bitter, cynical, and self-indulgent, interested in undoing the forms of life that are self-evidently good to those living outside the city.

The effect of power shifting to the city is the unleashing of materialist impulses. Materialism and the will-to-power always go hand in hand. The latter always seeks to consolidate power within and assert it without. As consolidation and assertion take place, they will necessarily elevate the importance of parties and money in political life, leading to greater competition for power among the most ambitious.

“…we find in every Culture (and very soon) the type of the capital city. This, as its name pointedly indicates, is that city whose spirit, with its methods, aims, and decisions of policy and economics, dominates the land. The land with its people is for this controlling spirit a tool and an object. The land does not understand what is going on, and is not even asked. In all countries of all late cultures, the great parties, the revolutions, the Caesarisms, the democracies, the parliaments, are the forms in which the spirit of the capital tells the country what is expected to desire and, if called upon, to die for.”

Within this process, Spengler argued, no one is inclined to ask about the role or place of the state. They would be solely concerned about whether it secured men’s “rights.” Essential to this idea, Spengler believed, was the process of disassociation, “the rootless fragments of population [that] stands outside all social linkages.” Not attached to a place, an Estate, or a vocation, these deracinated types are easily collectivized into and placed in the service of the power structure. Money becomes the key, for once divorced from the “prime values of the land” it can be used to pay off the public. All political problems become problems of money. “Intellect rejects, money directs – so it runs in every last act of a Culture-drama, when the megalopolis has become master over all the rest.”

Freedom of life from the soil, freedom of thought from institutional or cultural limits, and freedom of money to go where it wills all serve, Spengler said, the purposes of the state. For the West, the consolidation of power and money into the state apparatus was its “destiny,” and also its decline.

Washington is a place where power is mongered and advantage sought. It is a city that, as Federal Farmer said, has taken its tone from the character of the persons it necessarily collected there. “This city,” he wrote, “will not be established for productive labor, for mercantile, or mechanic industry; but for the residence of government, its officers and attendants. If hereafter it should ever become a place of trade and industry, in the early periods of its existence, when its laws and government must receive their fixed tone, it must be a mere court, with its appendages, the executive, congress, the law courts, gentlemen of fortune and pleasure, with all the officers, attendants, suitors, expectants and dependents on the whole, however brilliant and honourable this collection may be, if we expect it will have any sincere attachments to simple and frugal republicanism, to that liberty and mild government, which is dear to the laborious part of free people, we most assuredly deceive ourselves.”

George Clinton feared that the city would become the “asylum of the base, idle, avaricious and ambitious,” and that the government would become so remote from the concerns of “the extremities” that it would “be compelled to impose a crude, uniform rule on American diversity.” The city, A Farmer averred, would be one where wealth “will be collected … into one overgrown, luxurious and effeminate capital to become a lure to the enterprising and ambitious.”

Indeed, Washington has gotten rich, and as a recent story in the NYTimes said, its boom has been financed by you. What boom? Washington is the richest city in the country. It is growing at 3 times the national average. Direct federal spending counts for 1/3 of its economy. Four of the top five and nine of the top fifteen richest counties in America are in the DC area. Metropolitan Washington has a high concentration of what Charles Murray calls “SuperZips”: places noted for their wealth, education, homogeneity, and cultural isolation. Indeed, Murray’s main point is that they inhabit a different culture. DC’s downtown areas – including the gentrified H Street corridor – are filled with bustling restaurants and bars, and one sees cranes everywhere symbolizing all the new building taking place.

Even the reporter in the NYTimes admitted that “there is something unseemly about having a capital city doing outrageously well while the rest of the country was limping along – especially when its economy is premised on capturing wealth rather than creating it.” And even independent of federal spending, the amount of money flowing into the capital has increased dramatically as a result of interest groups. In 2000 $1.66 billion was spent on lobbying, and by 2011 that amount was $3.3 billion. While Washington takes in 1000 new citizens a month, it continues to fill its coffers. Its pension program, for example, is the second best-funded in the country, with 104% of the assets needed to fund its liabilities (compare this, for example, with Chicago, which is at 52%).

Then too, there is the geography of Washington: monumental in scale and architecture, all designed to communicate a feeling of power while at the same time enshrining the canons of America’s civil theology. “Make no little plans,” said Daniel Burnham, the man behind the 20th century architectural plan that resulted in most of the buildings we see today, “they have no magic to stir men’s blood.” (If you walk down Constitution Avenue you will see sign after sign with this quote on it.) Washington is a place inhabited by rich families in the SuperZips, by 20-something singles who want bars, restaurants, nightlife and shopping and who embody the nihilistic chic of contemporary culture, and by the avaricious and ambitious. It is a place no one is from but people flock to because it is a “cool urban place.” In terms of its monumentalism, culture, and wealth, it really is an avatar of America, but only in a parasitic sense.

A “world-city” is not a home; rather, it is a place of domination and control, a phenomenon indicative of any culture in its late civilizational phase. Everything not of the capital city retains only a shadow of political existence. The movement of power and capital to the capital has the effect of eviscerating traditions, operates on abstractions such as money and noble-sounding but vacuous ideas, and destroys the ranks and institutions of social life.

I lived in DC from 1985 until 1994 and enjoyed those years. Toward the end I started getting a serious itch to return to the midwest. Returning now the city seems to me soulless, characterless, inhuman in some fashion. The capitol, the memorials, the museums – none of them connect to the heart like dipping in the salt-free waters of Lake Michigan, a lake trout snapping on a J-plug, the tulips blooming in early May, or a run down a sandy dune — all bringing into relief the federally-funded battery plant which continues to non-employ people.

I’m not sure I want to get entirely on board with Spenglerian pessimism, but then I don’t live in Washington D.C., from which the view is no doubt pretty bleak. Here in the hinterlands of Montana, there seems more cause for optimism, but it may just be the mountains all around and God’s blue sky above us. In any case, and as much as I hate to cite Pat Buchanan, what was intended as a republic has become an empire, with all the sorrows that implies. I wouldn’t live in D.C. to save my life.

It seems clear to me that here in the 21st century there’s really no reason for a capital city. Let the people’s representatives live among the people, at home, and “convene” via the internet. I suppose the executive branch needs to be more centralized, but it’d be far better if legislators had to answer to their neighbors every single day rather than being cocooned in that wretched hive of scum and villainy.

Now I know more about the Jeff in Jeffersonianism. On one hand, I relate to the natural vitality of rural America and small town trusted relationships. On the other hand, I have learned and listened to the great cultural products of the city. In my case it was NYC. I have been nourished by both of the above. Washington is in a league of its own and aside from the tourist venues, the capitol seems hollow and cold—devoid of human relations of warmth and love. But I realize that the exceptions are too numerous to count. The allness indicators of Polet need some shading also. Even Jesus likely spent a fair measure valuable time in Sapporis near Nazareth.

You should have seen our cities in the 70’s when Travis Bickle was spawned. today’s cities are entirely more salubrious, if a tad nettlesome, as they have always been.

It is never a choice of which city we must inhabit. This is not a choice for us to make. We inhabit the place of our temporal existence as best we can, holding the other city inside, in all its vastness and light. Hopefully, as we go about our business, we let some of the atmosphere of the City of God embellish our temporal existence wherever we might go.

This human tension is our recompense for manifest hardship.

I recommend Louis Halle’s Spring In Washington for an antidote. You are on a major flyway.

You act like there is no nature in or around DC ?

Move back to Detroit.

DC modeled after Paris is the most free

& most beautifully naturally expansive city in the USA

It is your political ideals that are causing your depression.

Do not blame all the other inhabitants.

Really, a city where no one is from? I suggest you talk with some black people. There is a reason its earned the nickname the “chocolate city.”

Moreover, even though people flock to it, many others leave all the time to go back to their home states after a while. People do not settle in DC like they do in London, Paris, Moscow or other cities. Maybe this difference is kind of important?

I agree that the city is changing greatly in recent years, but is all of that bad? I don’t know how you can say you liked DC back in the 1980’s and early 1990’s when it was the murder capital of the country. It missed most of the economic prosperity of the time and is only finally developing after people realized it had a lot of potential, e.g. the economic anchors of Target at Columbia Heights, Walmart in the Southeast, etc. The place is a lot safer now than it has been for years.

Comments are closed.