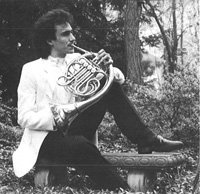

Arthur Brooks dropped out of college when he was nineteen. He played French Horn in orchestras and ensembles around the country. He joined the City Orchestra of Barcelona. He had a wife and a small child. And he was unhappy.

Brooks called his father to tell him that he was planning on quitting music and going back to college. His father said, “You can’t do that, you have a wife and a child.” Brooks told him about his unhappiness. His father asked, “What makes you so special?”

Arthur Brooks has written several books on the topic of happiness. He delivered a lecture on “The Secret of Happiness” on October 1 in Washington, D.C. I attended the lecture and anticipated eagerly his insights on this ever-fascinating topic.

The exhortation to pursue one’s calling is all around us. In graduation speeches, in articles, in books, we are told that if we can only match our skills to our passions, we will never “work” a day in our lives. We will start every morning excited to get out of bed and tackle the day’s tasks. We will end every evening satisfied with our existence. If only we could find our “calling.”

Brooks began his lecture by explaining that, according to several studies, happiness is a function of three major factors: genetics, major life events, and choices. Social science research connecting happiness to one’s genes is increasingly prominent. Social scientists and biologists talk about a so-called “happiness gene” that regulates the way serotonin is delivered to cells. Serotonin is key to reducing stress levels in the body. The research varies, but Brooks synthesized several studies to propose that 40% to 48% of a person’s happiness is a result of their genes.

Brooks’ second category, major life events, accounts for 40% of happiness. But, Brooks argues, major life events are a bad candidate for unlocking the secret of happiness. Why? Because the satisfaction gained from major life events is usually temporary.

Brooks’ second point is connected to another trending idea, that of the “hedonic treadmill.” According to some social scientists and psychologists, most human beings return to a baseline of happiness within a few months to a few years of experiencing very positive or very negative events. For example, an increase in income or a job promotion tends to boost happiness for six months to a year before a person returns to their pre-event happiness baseline. This may also be true for very negative life events. According to one study, accident victims who sustained severe spinal cord injuries experienced overwhelmingly negative emotions one week after the event, but eight weeks after the event their positive emotions outweighed their negative ones. Thus, the theory goes, we have a set point of happiness, which major life events can move for short periods, but in the end the baseline reestablishes itself.

That leaves Brooks’ third category as the most likely place to find the key to happiness: our choices.

Although they are responsible for a mere 12% of our overall happiness, choices allow us to maximize our happiness potential. If we are unlucky enough to have the wrong genes or to experience severely negative major life events, then making choices is where we can make up the difference.

Now, I thought to myself, we’re getting somewhere. Brooks’ audience was surely sitting on the edge of their seats to hear how their choices could unlock the secret of happiness.

Brooks argued that, according to the social science research, income, career success, and education have relatively little correlation with increased happiness. By contrast, faith, family, community, and work had significant correlations with increased happiness. So there it was: faith, family, community, and work. These are the secrets to happiness?

But what do these words mean? How do we choose both faith and community when there are deep disagreements in the culture about gay marriage, public education, and increasing religious pluralism? How do we choose work and family without despairing that we will end up doing neither well?

Brooks brushed past these conundrums. He told the audience that he would only discuss the last item on the list, “work.” He explained that work in the fullest sense means the ability to build your career as your own enterprise. It means that at the end of the day, you feel that you have added value to the world. Satisfying work is, as he called it, “earned success.” And earned success is only possible within a free market system, the kind of system we have here in the United States.

If each one of us would only be a moral warrior on behalf of the free enterprise system, we would contribute to the greater happiness of all Americans. If we could export that system around the globe, we would contribute to the greater happiness of the human race.

I hope I was not the only person in the room disappointed.

Brooks argued that the secret of happiness was easy and obvious. The social science research was clear. If American policy makers would only listen to the plain facts, they would get on board with the small-government free-market agenda and thereby contribute to the most morally commendable political arrangement the world has ever seen.

But Brooks failed to address the tensions that exist within his own recipe for happiness. Is there not a sense in which a commitment to “earned success” potentially undermines a commitment to community? What happens when upward mobility means moving across the country, or across the globe, delaying family and children, in order to achieve earned success? Or, what do you tell the mother of small children who has sacrificed the pursuit of excellence in a worldly career in order to nurture her family? While one might make the case that the connection is obvious between happiness and “faith, family, community and work,” it is far from obvious whether or how those things go together.

The real complexity and mystery of happiness deserves better treatment. And mercifully there are some, other than Brooks, who have been willing to grapple with the tensions, contradictions, and paradoxes of happiness. Writing in 1941, Reinhold Niebuhr had something to say about happiness. Particularly, Niebuhr wanted to explain why happiness is so elusive for human beings. It has to do with nature and transcendence, for human beings are both limited and free.

Niebuhr observed the tendency throughout human history to associate happiness with either nature or transcendence. Either unity with natural things was the key, following Epicurus or Rousseau. Or identity with universal reason was what was needed, following Plato, Hegel, or Kant. But, Niebuhr wrote, they all got it wrong. Human beings will never be free of their dual nature. And as long as this life persists, we will never escape the unease produced by our condition.

As Niebhur explained:

Yet they were all false. Whether they found the path from chaos to order to lead from nature to reason or from reason to nature, whether they regarded the harmony of nature or the coherence of mind as the final realm of redemption, they failed to understand the human spirit in its full dimension of freedom. . . .

The human spirit cannot be held within the bounds of either natural necessity or rational prudence. In its yearnings toward the infinite lies the source of both human creativity and human sin. In the words of the eminent Catholic philosopher Etienne Gilson: ‘Epicurus remarked, and not without reason, that with a little bread and water the wise man is the equal of Jupiter himself. . . . The fact is, perhaps, that with a little bread and water a man ought to be happy but precisely is not; and if he is not; it is not necessarily because he lacks wisdom, but simply because he is a man, and because all that is deepest in him perpetually gainsays the wisdom offered. . . . The owner of a great estate would still add field to field, the rich man would heap up more riches, the husband of a fair wife would have another still fairer, or possibly one less fair would serve, provided only she were fair in some other way. . . . This incessant pursuit of an ever fugitive satisfaction springs from troubled deeps in human nature. . . . The very insatiability of human desire has a positive significance; it means this: that we are attracted by an infinite good.[1]

Happiness eludes us, not because we are unaware of the facts, but because of the reality of our nature. We seek an “ever fugitive satisfaction” because we cannot resolve the tension between our embodied limitation and our soul’s freedom. If there is a secret to happiness, it lies here, in the “troubled deeps.” Brooks’ easy diagnosis and “moral warrior” solution merely scratch the surface.

There is a paradox at the heart of happiness. As Niebuhr explains, we desire happiness, yet we also always desire to transcend our present condition. If you could choose to devote yourself to your calling (if you could determine what that is), even then you would wrestle with the desire to achieve greater levels of mastery, influence, or understanding. Indeed, if you gave up such a pursuit, you would be likely to become bored and therefore unhappy. The secret of happiness lies in inhabiting this suspended contradiction. And it is a contradiction rooted in our very nature as human beings. There is no economic system, political effort, or ideal career that can remove it.

If Niebuhr’s description is persuasive, then the secret of happiness is something that is neither purely natural nor purely transcendent. It is something that feeds our desire for the infinite without leaving us disgusted with our merely historical existence. It is something that invigorates our relationship with nature without denying our spiritual freedom.

It is something like a story that transports us into an experience not our own while at the same time making us grateful for the warm reality of family and loved ones. It is something like a relationship with a friend or a spouse, who desires to see you grow but also accepts you just as you are, right now. Indeed, it makes sense that the secret of happiness would be like a relationship with a person, because people are both natural and transcendent.

Perhaps Brooks could not go into all of this in the limited timeframe of his lecture. Perhaps he made a choice to explain work and leave the exposition of faith, family, and community to another time and place. But his overwhelming focus on work obscures the real distance between work and happiness by eliding a crucial fact: that whatever we do, within whatever economic system we do it, the secret of happiness ultimately has less to do with earning and more to do with relating, to ourselves and to the other transcendent souls in the world.

Samantha Sewall is a lawyer who works in Washington, D.C. She lives in the Del Ray neighborhood of Alexandria, Virginia, with her husband. She enjoys brunch and not cleaning on the weekends.

Photo courtesy of the American Enterprise Institute, Inc.

[1] Reinhold Niebuhr, The Nature and Destiny of Man (Louisville, Ky: Westminster John Knox Press, 1996), 122.

Thanks for this. A really edifying read.

Happiness, or blessedness, is a result of obeying God.

John Lofton

Director,The God And Government Project

https://www.facebook.com/pages/The-God-And-Government-Project/494314250654693?fref=ts

JLof@aol.com

And then there’s the recent research that says happiness is directly related to having a sense of meaning in your life. That indeed can be found in faith, family, community and work. I am glad I volunteer in ways that make a difference to someone else, not me.

Why do they always reference Epicurus and ignore Epictetus?

Saving only the negative PR from the hedonists, who seem to love giving the Stoics a bad rep, the Romans Epictetus, Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, has a lot to say about happiness, its nature, where to find it, and how not to attain it. Not the silliness of looking for happiness in pleasure or transcendence or political economics, but in the quotidian.

Comments are closed.