As Mary Eberstadt has recently pointed out over at First Things, evidence is accumulating that the current day usage of pornography is taking a toll on marriages and families. And, as Reinhard Hutter later added in a different FT issue, it is also becoming clear that regular pornography consumption both results from, and underwrites, a form of spiritual torpor and listlessness that ancient thinkers called acedia. Hence it is now possible for critics of porn to say “I told you so” with the same degree of conviction that porn advocates redouble efforts to explore yet another frontier in the mechanics of eroticization. End of story?

Perhaps it should be, given that most other discussions about porn result in a push-and-shove battle between people who believe that the appearance of porn is a sign that our culture is depraved, and others who believe that the phenomenon has been been evident in strong societies as well as weak ones since the beginning of time. I wonder, though, if there isn’t another, possibly more productive way of thinking about the meaning of porn that is usually unavailable or at least hidden from view, given porn’s more obviously sensational aspect. For porn isn’t, ultimately, about sex. It’s not about bedding somebody in front of a camera, it’s not about the effort to incite interest in a viewer, it’s not about striptease artistry. Instead, porn has to do with immediacy. It comes to pass, it gets enacted if you will, whenever and wherever people provide access to the literally unspeakable and in that way lose our only sure access to a zone that most of us naively and perhaps not so naively refer to as “the real”.

Where does it come from, this pull toward immediacy? What are its historical causes?

It has been argued rather famously by Richard Weaver that interest in immediacy dates from the early 14th century, which is when William of Occam first devalued the conceptual aspect to words, but for our purposes, here, it would probably make more sense to simply remind ourselves of our identity as Americans — which is to say, our tendency to think that “truth” and “the thing itself” reside on the other side of a constructed metaphor, essay, speech act, or story. As Toqueville quickly noticed, we Americans read newspapers in order to get information, and if we can do that quicker or more efficiently without words, so much the better. Hence we are predisposed to go “visual”, and once daguerretypes appeared we upped the ante still further by turning principally to photographs to get our information, rather than to paintings with their brush strokes, or sketches with their wobbly lines.

With a photograph you get almost perfect transparency and the fictitious thing-in-itself is brought tantalizingly near! Much as a balsam matrix, cover-glass, or microscope invites a viewer to almost feast on the clarity of a biological specimen, so too do photographs create an illusion of almost ecstatic “actuality”. Hence we began to return, time and time again, to the photograph, and that habit, in turn, makes for a “new” one, which is the desire to feast on whatever is explicit, edgy, or raw. Sometimes the subject luring our attention is sex. Sometimes it is suffering or humiliation. At other times it is birth, and one day, perhaps, it will be death. But whatever form that rawness takes, we Americans have historically aspired to taste it, and starting in 1962 we began also to know it and even systematically revel in it as the sheer blast of frightful immediacy that it is.

Most of us are familiar with Greenwich Village neo-folk, the offshoot of Alan Lomax’s interest in musical “roots”, and John Hammond’s “discovery” of Bob Dylan imitating Woody Guthrie who had in turn imitated union hall organizers imitating harmonica-playing hobos. What is less often known is that the success of the young Dylan was directly related to the appearance, in gay circles, of a fondness for “kitsch” – which is to say, artistic efforts (velvet paintings, early ads, socialist propaganda) whose sentimentality, tackiness, and obvious falseness put them in a class of their own and even compelled attention as a kind of hotbed for the cultivation of irony. Raw (unmediated) folk “expression” on the one hand, patently decorative (clearly non-revelatory) art on the other — the two fads fueled each other thanks to a kind of oscillatory dynamic, and, as such, their simultaneous appearance indicated the removal of art that effectively transmuted, or “heightened”, the materials of ordinary experience. I do not mean to say that certain artists working within these two movements did not, in the end, transcend their medium. (Here I think even of Dylan’s “free-wheeling” songs, let alone the Chess Records sound he later drew from, and too of Susan Sontag’s marvelously strong, camp- influenced essays.) Rather, I am talking about the movements proper, the collective leanings that they represent, leanings that were soon to be even more dramatically evident thanks to an exhibition of paintings staged in November, 1962 at the Sidney Janis Gallery on East 57th St, a short taxi ride north and east of Greenwich Village.

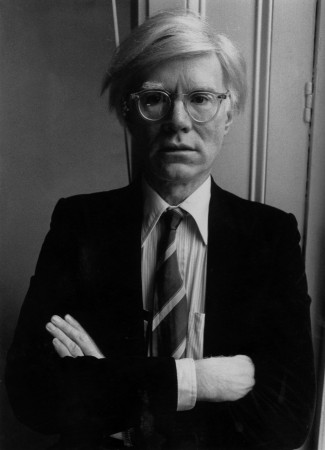

That show featured works by a range of mostly American artists who were reacting against abstract impressionism and instituting, in its stead, a new kind of frankly representational painting that depended on found “objects” like mass-produced images. Given that Jackson Pollock et al were the ruling class in the art world at the time, this Janis show would have made a splash in any case but in November 1962 the baton- passing aspect was especially dramatic, for most of the artists featured in the 1962 show celebrated the relative opacity of mass-produced images – their flatness, their peculiar deadness, their inability to convey the essence of whatever it was they “signed” – at the same time that they delighted (via scrupulous attention to “realistic” detail) in bringing that object close and making it seem as though it was immediately apparent, right there, present in that very room. For example, Robert Indiana de-contextualized the alphabet, in order to accentuate flatness at the very same time that he imbued letters with deep, vibrant hues. (See his Scrabble-like arrangement of “L”, “O”, “V”, and “E”.) Roy Lichtenstein, for his part, lovingly “reproduced” the grainy, newsprint texture to comic strips at the same time that he presented, at face value, the stunningly vapid “crying beauties” populating them. But the true star of that show was Andy Warhol, who had hung a few paintings of tin cans in a corner.

Warhol had gotten his start as an illustrator in the employ of Bonwit Teller. He had a whimsical eye, and built-in fondness for old-world calligraphy mixed well with quirky line drawings of leather shoes, green apples, and butterflies. Hence Warhol began to exhibit professional work at galleries, and when Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns began to use imagery from ads and news tabloids as starting points for serious painting, Warhol realized that his experience as a commercial artist had, curiously, put him in a good position to make his own run at the pressing aesthetic issues of the day. For a while he toyed, like Rauschenberg, with instantly recognizable comic strip characters and the various kinds of lettering employed by comic strip creators. But he didn’t really hit his stride until, one day, he found himself appraising a drawing he’d made of a can of Campbell’s Soup. Warhol had copied the object before him so well that the can in his picture was almost more real than the can on the table! Indeed, it appeared to be more real, for now the can positively shimmered with the kind of there-ness that comes with the illusion of complete transparency (zero mediation) and total access. “BOOM!” Warhol was off and running. Elvis posing with a six gun, Marilyn, S&H Green Stamps, 200 cans of Tomato Soup – from 1962 onwards, viewers of Warhol’s work were treated to a kind of orgy built on perfectly achieved copies.

And then, starting just a year or two after the Janus show, Warhol began inviting viewers to more conventional orgies – the kind that involved nudity and sexual acts – in Warhol-directed films like “Blowjob” (1964), “Blue Movie” (1968), and “My Hustler” (1968).

Thanks to movies like these, of course, a lot of people began to dismiss Warhol as a prankster who had worn out his welcome. In fact, though, Warhol’s pornographic movies were the natural outgrowth of his earlier work with soup cans. Indeed, they cemented his position as an artist rather than destroying it, for now Warhol was making the implications of New Realism clear. What, after all, was the point to these movies? The point – and it was, in retrospect, a very clear point as the sex itself was far from exciting — was that acting was just as superfluous, when push really came to shove, as painting. The footage in “Blue Movie” was “real”. It was (like a silkscreen) stenciled off actual events, and given that this particular emphasis demonstrably commanded attention in ways that traditional emphases did not, Warhol was also arguing that footage resulting from such an emphasis rightfully supplanted less immediately interesting “stories” that had been invented to convey truths not available to real-time witnesses of ordinary life. Was this a good thing or a bad thing? Warhol, I feel sure, did not presume to know. Instead, he simply knew – a little before the rest of us — that our culture had changed. Thanks to his experience as a practicing communicant at St. John Chrysostom Byzantine Catholic Church in Pittsburgh, and then (throughout his adult life) as an abstaining communicant at St. Vincent Ferrer Church in Manhattan, Warhol understood genuinely word-based culture. It was a given, for him, that ordinary experience was ably known through the mediatory presence of a sign that was different from the thing one was proposing to “know”, and therefore when that bias in favor of logos-based art began to dim in the culture at large, Warhol noticed.

How long has it been since Warhol’s “Blue Movie” – 35 years? If you count from Traci Lord’s rocket blast to fame, the amount of elapsed time is not even half that. Yet already a world that had been merely presaged by these two formerly shocking events is upon us.

Consider the current-day “hyper-real” movement, which is championed by the computer-graphics industry and driven by a confirmed consumer preference for instantly recognizable, visually certain “signs” regardless of whether or not these signs truly link up with the things they formerly or perhaps even never honestly indicated. Think touched-up photos of dewy cans of Coke with clearly defined beads of moisture on cool, aluminum bodies. Think Mickey Mouse on Main Street at Disneyland USA. Think green-ness alternating with yellow-ness in a British Petroleum “sun” flower. In each of these instances, the criteria for reality and ensuing convincement have ceased to have any relation to referents outside the zone of signs. Rather, the criteria have become exactitude of detail, inherent desirability (even horrific images can be desirable), inner coherence, and compatibility with other, similarly unmoored “signs”. Hence fantasy and manufactured advertising images both qualify, now, as “reality”. Does anybody know where this movement will wind up? I sure don’t, and I suspect that it would be wise to never try to learn. Or consider “reality TV” and its theatrical equivalents, where the viewer’s “charge” comes from the realization (no pun intended) that the drama unfolding before one’s eyes is “really happening”. It used to be that we went to the movies or a theatrical production to give ourselves over to an obviously invented fictional world, and thereby gain a glimpse into the meaning of our ordinary, humdrum lives. Now we go to the movies or the theater to trade that contract in for a different one whereby theatricality gets removed, often by annihilating the difference between audience and actor to create a passing sense of immediacy.

Big though these developments are, however, they are nothing compared to the widespread acceptance of porn and its consequent enhancement. The stuff is often rocket fuel now; much of it has the power to burn holes in your mind. Partly this is the result of producers’ newfound ability to be selective about who to employ as a performer.

Chiefly, though, porn now provides a thruster-like boost because, like an uncut drug, it delivers an almost pure form of immediacy. First there’s the rush of naively defined reality made possible by the knowledge that “actors” on the screen are “really” having sex, and then, once that sensation starts to wear off, there’s the intensified “there-ness” of perfectly wordless – e.g. intentionally transparent, therefore unspeakable — knowledge.

Is the correct analogy, here, the rapid ignition of fossil fuel that ought, ideally, to be burned or otherwise broken down more slowly? Whether or not that analogy is correct, one can at the very least note that going for broke toward simulation by literally feasting on “things-in-themselves” paradoxically leads viewers to ignore the very same referents that word-signs stubbornly point toward. Indeed, consumers of high grade porn get to the point where they resent reminders that an “objective” world of, say, potential sexual partners exists, and that development, in turn, causes viewers to mentally replace the dangerous world of people with the plastic, oh-so-subservient world of candied images. Has there ever, anywhere, been a more radical overturning of word-based knowledge? Immediacy, orientation toward fantasy, dividends up front rather than down the line, fixation rather than contemplation – it’s all there. Modern-day porn, it turns out, has functioned and continues to function as a kind of final cause. It’s the end toward which Warhol and Derrida and indeed all advocates of nominalism have tended. When Occam dismissed words as screens, he was pointing toward porn.

Words, however, are not screens. Just as the real is not positivistic fact, or a Kantian projection, or a fiction created by a power-wielding subject, so too words are not ciphers that “stand in for”, package, or cloak a referent. Rather, they are first and foremost a kind of parallel creation, a variously complex zone where material vocables are infused with sense in such a way as to re-present the natural world and thereby share in (and convey) the splendor of that world’s being. Sure, verbal signification involves “likenesses”. One of the chief points, in talking, is to see, over here, the very same thing that we see, over there. But words themselves, both as single names and as elaborately constructed clusters of names, have nothing to do with copying or imitating or (as in trompe l’oeil painting) inviting an audience to mistake a two-dimensional sign for a three-dimensional referent. Instead, words have to do with communicating presence.

Words permit things to glow anew and be recognized for the marvels that they are. Even more incredibly, words accomplish this feat in direct proportion to their obvious difference from the things they represent. Unlike simulation-based enterprises like porn, word-based knowledge depends on there being a remove from the object being apprehended. Eliminate that remove – strive as Warhol did to do an end-run around mediatory agents and “lock in” on lurid, triumphantly visual spectacles like Orange Car Crash Ten Times – do that and the whole enterprise collapses. There are practical reasons for this collapse. For example, if one eliminates the possibility of detachment and the freedoms contingent on that detachment, one also eliminates the possibility of epiphanic experience, or what Joyce called “aesthetic emotion”. But the bigger reason for such a collapse may simply be metaphysical, for the sheer neatness with which words reveal nature suggests a common base. It is almost as if the world was made to be named.

Who, though, can we turn to besides pre-postmodernist writers, poets, and our best commonsensical selves in an effort to get a firm and detailed grasp of what we’re losing as we turn away from word-based knowledge?

The best place to start is by examining the Scholastic tradition that blended Johannine logic with the Platonic theory of Forms successfully enough to invite repudiation by Occam, for thinkers like Bonaventure, Duns Scotus, and Hugh of St. Victor didn’t spend their time trying to figure out whether angels could stand on the head of a pin. On the contrary, they spent their time trying to explain the blazingly evident fact of fleshly existence in all its time-bound specificity. They were interested in things – the force of them, the demands they placed on our attention, the way they glowed with there- ness. What was a blade of grass? How did it maintain identity through change? Wherefrom the obvious intelligibility and to what extent was that intelligibility proof of a thing’s existence?

Nowadays, only children ask such questions. The rest of us, ostensibly because we are more experienced and less epistemologically naïve, have moved on to map genetic structure and think through the uses of grass. But people living in the medieval era asked about what-ness well into their adult years, owing to their belief that God had in some sense spoken the world into being two times – first during the Genesis event, second during Pentecost. They were inclined to read nature itself as a kind of divine word that “meant” an idea in God’s mind. Additionally, they believed that they were in some sense commissioned to share in that creative act by naming objects and knowing them in the light of a human word through which objects continue to “finally” exist. Hence the entire world shimmered with import, in the medieval mind. It was “real”. Owing to the average medieval person’s bias in favor of verbal signification, nature itself was a burning bush, and therefore Medievals spent their entire lives trying to account for the phenomenon.

Well, who needs a burning bush? We have regular ones, and if they don’t suffice we can bask in the intensity of the hyper-real! Why, that medium boasts more colors – heck, more (species-free) forms – than Aquinas even dreamed of! Yes?

The truth is, we know we are lying, when we talk like this. Moreover, we even understand the hugeness of our current predicament, as patrons of porn. For it is not just accidental that we are gravitating now toward events like the ones on “reality” TV. On the contrary, it’s an indication of our conviction that something valuable called “the real” is eluding our grasp and disappearing even as we speak. The world is growing dark! Juniper twigs, hop petals, flecks of feldspar in granite, the eyes of a tern, even a stripper’s fetching legs are fading fast and therefore we are desperately reaching around for ways to shore up the failing there-ness, we’ll give even virtue a try, but the inertial pull toward immediacy is strong and so far we are powerless to escape it. Hence we push on, toward night.

A new award-winning documentary, “Risky Business: A Look Inside America’s Adult Film Industry,” examines many of the current issues surrounding the adult film industry, including many of the items addressed in this article. The film’s website is RiskyBusinessTheMovie.com

Actually, porn needs no new or involved explanations. I can say this with confidence because it’s extremely consistent over time and space. Greek vases and Roman grafitti were already using the same themes, and there’s strong evidence that the same stuff was around in the Paleolithic. Those so-called “goddess” figurines.

In essence, porn is to the ubiquitous reality of sexual fantasy as oral or written tales are to daydreams embodying other types of fantasy, of wealth or adventure or strange places. Everyone has ’em.

The difference now is that there’s just -more- of it; but then, there’s more of everything.

@S.M. Stirling: the point of this article was to explain how today’s “hyperreal” pornography is qualitatively different from that of the past — you appear not to have read it.

Counseling ambivalence toward today’s ubiquitous high-definition internet porn because of depictions of sexual intercourse on “Greek vases,” etc. is like being unconcerned about the world-destroying power of nuclear weapons because of evidence that early humans in battle killed each other with clubs.

Comments are closed.