Rock Island, IL

The late British composer, John Tavener, wrote out of an apparently deep respect for Eastern Orthodox Christianity, the tradition to which in 1977 he became a convert. In the mid-1980s he wrote a commissioned piece for cello and strings called The Protecting Veil, named for a feast instituted by the Church in the early tenth century.

“At a time of grave danger for the Greeks from Saracen invasion,” Tavener wrote in his own note to the piece, “Andrew, the holy fool, and his disciple Epiphanios saw the Mother of God during an all-night vigil. She was high above them in the air, surrounded by a host of saints, praying earnestly and spreading out her veil (or stole) as a protective shelter over the Christians. Heartened by this vision, the Greeks withstood the Saracen assault, and drove away the Saracen army.”

Of the piece itself Tavener wrote, “I tried to capture some of the almost cosmic power of the Mother of God,” who is “represented by the cello, and never stops singing throughout.”

Tavener was mostly revered during his career, though not always and not by everyone. Over a decade ago a writer for the Telegraph said that Tavener’s large popular audiences “feed on the fact that his work is undemanding of concentration.”

My own experience of Tavener’s music, The Protecting Veil in particular, does not accord with this sneer. Nor, I suspect, does the experience of many others, though the quip does at least serve to remind us that dismissive comments will always outnumber appreciative ones. Debunking is easy; criticism is not.

I am not a music critic and make no pretense of being one. But, like many people for whom music falls somewhere between passion and avocation, I have attempted to be a good and careful listener and a worthy heir of our musical heritage, which had seemed an embarrassment of riches even before Tavener came along. And then he came along—he and others of his generation: Arvo Pärt, Henryk Górecki, and Benjamin Britten, to name only a few whom I have managed to attend to and, in my bumbling way, admire.

I don’t remember my first encounter with The Protecting Veil, which, with its allusions to Byzantine chant and its use of the Byzantine tones, is (as Tavener himself said) a “lyrical ikon in sound,” but I think my first hearing was fairly soon after the premier in London a quarter century ago, and I confess I am as taken with the piece today as I was then.

Although like many people I am fairly well habituated to distinctly Western music, and although I find it difficult to keep in abeyance the sense that a piece of music should satisfy my expectations for narrative development nurtured in the folds of that same habituation, it is precisely Tavener’s stinginess in this regard that brings me back to the piece time and again. Very little of the music I know expresses as well, by this kind of withholding, the timelessness that Tavener apparently wishes here to communicate, and by timelessness I don’t mean “enduring” or “immortal” but, rather, that which, having reposed, is free outside of time to partake more fully of eternity. And by eternity I don’t mean that which merely comes after time, similar in kind but longer in degree. No. It is that larger thing that time itself turns out to be a very small part of. Eternity might be compared to an ever-expanding universe and time to a little solar system of a few planets and a sun going about their quaint entropic, if nevertheless important, business.

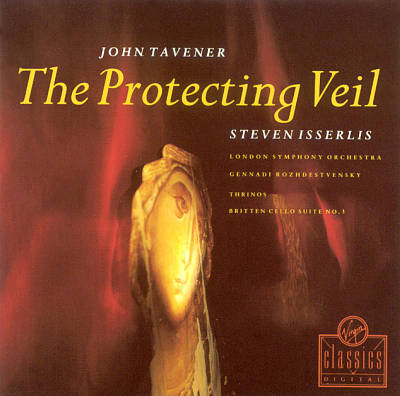

Having recently come into possession of a score of The Protecting Veil, I sat down to read it while listening to a recording. (I own the Steven Isserlis / London Symphony Orchestra version released in 1992 under the Virgin Classics label.) In doing so I was struck by many things, including my own ignorance, but especially by the tirelessness of the complicated cello line, the freedom for it that seems in places to be handed over entirely to the cellist, and what I can only call the uninterrupted earnestness of the cello in its entreaties. I won’t say I’m not baffled by parts of the score. I am. I bring to it a fairly limited intelligence. But I find myself deeply moved by the beauty of the grave and often soaring voice of the instrument that represents the woman who, as a young girl, said, “be it unto me according to thy word.”

If The Protecting Veil does not attempt to flatter established prejudices for movement and tonality, and I hardly think it does (except maybe in those odd six measures of apparent anomalous polyphony that occur in the Dormition section), the piece does nevertheless answer beautifully to the strict demands of unity. One way it does this is by returning on itself many times, most notably when the cello resumes its simple pattern of whole steps from F to A, then climbs from A to B flat to C, followed by that tender lyrical decent—D-C-B flat-A—and the modulated repetitions of this motif, all of which conspire to make a single beautiful song that frames the whole work, ending at last, in the eighth song, in a quiet gesture of something like pious ascent: an octave leap on the ultimate note, bass to treble F, pianissimo—and then the silence into which all prayer fades before it begins anew.

But this thematic returning, whatever its musical function as ritornello, seems also to be emblematic of the so-called prayer of the heart that has been a salient feature of Orthodoxy since about the sixth century, a prayer predicated on a simple repetition that, when rhythmically aligned with the breath—until, like breathing, it too becomes involuntary—turns life itself into prayer and makes possible the prayer without ceasing of which Saint Paul wrote, here a disciplined song perfected in the ongoing intercessions of the Mother of God, whom the music regards as the mother of us all as well.

Although much of the poetry that bears Marian devotion in the East differs considerably from the poetry that bears it in the West, where, since 1517, it has not always enjoyed its full ancient appeal, nevertheless there’s no denying that, so far as devotion goes, the Marian variety remains stubbornly enduring, whether on the banks of the Tiber or on the shores of the Bosporus. You might even say its power of endurance is supernatural.

In an age of irony and skepticism, indeed of disbelief less apathetic than antipathetic, there is something exceedingly touching, I’m inclined to call it comforting, in the thought of a mother’s vigilant and protecting entreaties, in a veil of immense love draped gently over this vale of immense sorrows. In that, certainly, there is nothing undemanding, let the critics say what they will.

Great piece, Jason. TPV is one of my favorite late 20th century orchestral works, and if you have to have only one recording Isserlis’s is the one. I can also recommend the one by Raphael Wallfisch with the Royal Philharmonic. I have Yo Yo Ma’s recording of it as well, but I find it a little too perfect, and perhaps a little “cold.”

Have you heard the Latvian composer Peteris Vasks at all? Not unlike Part and Tavener in some ways, but very much his own man. He’s written a lot of excellent stuff but I’m partial to his violin concerto “Distant Light,” his string symphony “Voices,” and his second symphony.

Oh, and there is a definite spiritual dimension to Vasks’ work as well. He too is a Christian, the son of a Baptist pastor.

Yes. A careful, thoughtful piece*. Thanks.

I understand the Telegraph’s criticism. The music discourages concentration, as it is capable of enveloping the listener in an amorphous veil of mystery, lovingly “protecting” us from too much intellectualizing. So, perhaps, it isn’t criticism at all. Ellington’s quip, “If it sounds good, it IS good.” seems more appropriate.

TPV is moving, yet the intense mysticism of Part moves me more somehow (perhaps because it doesn’t protect)… to feel, rawly, the wonder and heart of the universe, and our significant insignificance. Sublime expression transcends the particular theology that inspired it, whether it be Eastern Orthodox or Sufism.

Like Rilke’s:

“For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror

which we are barely able to endure, and it amazes us so,

because it serenely disdains to destroy us.

Every angel is terrible.”

A challenge: To feel with an open heart and to act in the world; or, at least, do as little harm as possible…

Thanks, Rob, for the Peteris Vasks recommendation. I’ll seek him out.

*(good work, dumbass.)

Comments are closed.