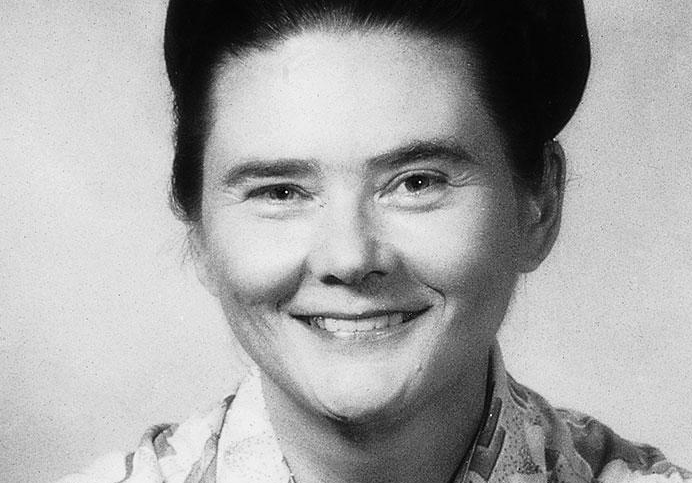

Louisville, Kentucky. “Reading Florence King is like opening a blast furnace,” reporter Liz Trotta said of her years ago. That fire is now out. The writer and satirist died on January 6th in Fredericksburg, Virginia, not far from the District where she had been born. She had been in failing health and had recently moved to an assisted living center, where communal living and dining may have broken her misanthropic heart.

Miss King wrote essays, a memoir, novels and was an excellent book reviewer, though her career began in pulp fiction. Her interests ranged from Madame Butterfly to Forever Amber, Fisher Ames to Lizzie Borden. She called herself, at least once, a conservative lesbian feminist, and she was not to be pegged and not to be trifled with. “I don’t mind being regarded as perverted and unnatural,” she said, “but I would die if people thought I was a Democrat.”

She was a wit, and she made her living by it. She understood that in a country increasingly fettered by dishonest speech, the best way for honesty to be heard—maybe the only way that has any chance of convincing—is to be funny. But she was as interested in the knockout as the laugh. “Any discussion of the problems of being funny in America will not make sense unless we substitute the word wit for humor,” she wrote. “Humor inspires sympathetic good-natured laughter and is favored by the healing-power gang. Wit goes for the jugular, not the jocular, and it’s the opposite of football; instead of building character, it tears it down.”

Here is one example of what she meant: “John Dollar is a novel by Marianne Wiggins, who is now in hiding because she is married to Salman Rushdie. Allah be praised.”

Though unconventional in some ways, she was a stickler in others: “In social matters, pointless conventions are not merely the bee sting of etiquette, but the snake bite of moral order.” And also: “Familiarity doesn’t breed contempt; it is contempt.”

Florence King’s best-known book, Confessions of a Failed Southern Lady, makes an airtight case for her failure, but then being ladylike was never her desire. She held to the standards of an 18th-century gentleman—she had a Squire Western sort of mindset, and in her certain irregularities were consistent with an otherwise severe sense of personal honor, and a remarkable (and poignant) independence. She was a fan of dueling in principle, and in an argument with Molly Ivins said she regretted it was not possible in practice. Her essays are full of anecdotes about what she called the necessity of Doing Right, and as a professional she was scrupulous about deadlines, worked hard at her prose, and had a justifiable reputation as a writer who hated being edited. But then she did not need much editing; I edited her for a while, and remember. (I did not know her well; still, she once inscribed a book to me by making a joke about a tin-eared man under whom we both had suffered. It was a tie to bind.)

She was the real McCoy: herself, and that sort of trueness takes grit.

I have not heard that she left any last messages, but it would have been like her to have arranged for a posthumous letter to be sent to the American Lung Association, to say that while she was now beyond amendment, decades of Lucky Strikes had not kept her from reaching 80 years and a day.

Peace to her memory—though she herself preferred the sword, I know.