[Cross-posted to In Medias Res]

Wichita, KS

The debate over health care reform in the Senate has moved into overdrive, with one possible compromise following another in rapid succession. The two crucial issues upon which the ability of the Democratic leadership to get the 60 votes needed to effectively move forward hinge are, as most folks who follow these things already know, the coverage for abortion services provided by many private insurance plans, and the exact make-up of the government-run “public option” insurance plan–or, as right now seems likely, whatever kind of regulated marketplace emerges in exchange for killing it. It is all, I frankly confess, way too much for me to be able to follow with the sort of patience and expertise it deserves, especially since I know everything could change by the time I finish this post. The most I can do is offer a slightly wider theoretical perspective, on why I am–mostly, anyway–on board with what the Democrats are trying to make happen, despite the fact that it may very well create a national bureaucracy that is neither particularly local nor especially democratic, two huge concerns of mine.

The very short answer is, blame Catholicism. But since, of course, I’m never satisfied with very short answers, I’ll go further.

I’m not Catholic, but Catholic thinkers–including, but not limited to, various pontiffs–have played a large role in my thinking about community and justice. Probably the primary reason for this is that the various strands of Catholicism provide one of the few deeply thought out attempts to authoritatively situate Christian morals and duties into modern, pluralistic polities. Central to the majority of these strands is the oft-abused but still essential concept of subsidiarity. I can’t do worse than to quote my old dissertation advisor here, Steve Schneck:

The root of the word is the Latin subsiduum, which is also the same root for our English word subsidy. Subsiduum was used, among other things, in reference to the morally weighted giving from those who had to those who had not…So, from its original root, subsidiarity invokes that hallmark idea of Catholic social teaching: the preferential option for the poor. Moreover, it shares with its root a context in the social order as a body-like whole, in which everyone has moral obligations vis-à-vis others in light of the common good. From subsiduum eventually comes the Latin subsidiarius, which refers to a person to whom a subsiduum should be given. In Roman-based systems of law, courts’ concern with compensation to a subsidiarius was to avoid either overcompensating or under compensating. Overcompensating, it was reasoned, undermined the ability of those in our care to take responsibility for their own duties to the community and society. It sapped initiative. Under compensating, just the reverse, would not provide enough subsidy to those depending on us for them to fulfill their potential for themselves and the social order.

Subsidiarius, thus, hints at an ethic at the heart of any correct understanding of subsidiarity, especially in application to questions about the proper role of government in executing public policies. Subsidiarity requires that policies be performed by the most appropriate level of the social order to achieve results without too much overage or too much underage in the application of power or resources. Overage creates unwanted dependency. Underage fails to fully satisfy needs relative to the common good.

This isn’t strictly an argument for subsidiarity as doctrine, of course; if anything, it’s an argument for common sense in the application of Christian principles of charity. Who wouldn’t want those in a position to give anything–money, first aid, advice, whatever–to be those in a position to know what exactly what was needed, and how it was needed, and how much, with the real needs and the integrity of the person in mind? But Catholic reflections on subsidiarity further allow that a “common sense” solution is also one that will work towards the common good of the whole community: strengthening the capabilities of and the relationships between individuals throughout the various “levels of the social order,” as Steve puts it, will be generative of more positive, more moral results overall. This makes sense to me; it appeals to my communitarian instincts, and it seems substantiated by events I’ve witnessed throughout my life, in my family and in my congregations and in the communities and societies I’ve lived in.

Of course, what does that have to do with health care reform? Nothing, necessarily: Steve concludes by observing “nothing in Catholic social teachings, including the idea of subsidiarity, requires that America’s health care crisis be addressed with a particular policy approach, whether by state, private enterprise, voluntary associations, or anything else,” and I assume he’s correct. That being said, this way of framing the question gets to the heart of the matter. Surely actual health care–the actual doctor or midwife or nurse examining you, healing you, offering you succor and relief–needs to be and ought to be as local and face-to-face as possible. But given that we have (for the most part gladly!) embraced many of the technologies and monopolistic reforms (such required medical degrees and licenses) that have limited, concentrated, and thus skewed the availability of the kind of extensive, often life-saving, medical care which doctors, midwives and nurses can provide these days, costs come into the equation. So the question is rephrased, as a commenter named Rex rephrased it in this post of mine from last summer: can medical insurance be local? So rephrased, the question becomes a different one entirely.

John Médaille wisely observed in a fine, follow-up post of his on health care reform that insurance programs almost invariably end up replicating the classic tactics of a monopoly, and this is especially the case when the insurance plans which most Americans use to pay for their medical care is tied to their place of employment; employers and insurers easily can–and regularly do–collude to create obstacles and perverse incentives that keep most employees committed to their (often increasingly restrictive) plans, not to mention creating pools of applicants (how many children do you have? what is your health history?) that often leave people with serious health needs out in the cold. Ideally, our system of employer-provided insurance would be scrapped entirely, making room for something a little bit more amenable to individual choice. But, given the realities of our political system, the prospect of insurance companies supporting a move by the national government to encourage alternatives to the sweet deals they have worked out with their various corporate and institutional parties over the years was never likely. Could, by contrast, the government impose common requirements upon all independently offered health care plans, so as to minimize the aforementioned skewed distribution of resources and costs? John rightly, I think, observed that if you were going attempt that kind of half-way reform, you might has well just have a single-payer arrangement, like they do in Canada. That would at least cut down on the duplication of administrative costs.

But the difficulties of our political system rise up again: single-payer was also never a truly serious option in this prolonged debate (though some have managed to keep the idea alive in the House version of health care reform, on a state-by-state basis). Which brings us to what we have in the Senate today–not even a half-way reform, but a quarter-way reform, at best. Still, even this quarter-way reform injects the national government into the question of medical insurance, through various acts of regulation, and through the possible creation of a nationally administered market of insurance exchanges (which may or may not include a government-run insurance plan, perhaps tied to existing government plans like Medicare, perhaps not). To many progressives, that’s more than good enough; it means many millions of Americans who either cannot obtain insurance or who are driven into medical bankruptcy by tragedies they were unable to fully insure themselves against will have the coverage they need to survive, and perhaps even flourish. But to those who take seriously the principle of subsidiarity, the question is more complicated.

Susan McWilliams recently wrote an essay which focused on young adults who cannot obtain insurance; her conclusion was that any society that had a grasp on its own common good would develop a sense of “intergenerational awareness,” which would bring us to recognize more fully the injustice and harm involved in so many young people having to forgo proper medical care because of the costs involved. The young should not, I think, be the primary target of concern here–following Christian teachings, I think the poor should be–but her post was a good one, perhaps especially because of the exchange it prompted between several commenters, John Médaille among them. In response to complaints (once again!) about “socialism” and health care, John trenchantly responded that “[i]n any community, there are obviously some services which need to be socialized,” adding that if “one is really opposed to socialism, then one ought not to pull that socialist lever in his home, the one that makes his waste disappear in a whirlpool into the socialized sewage treatment system.” I think that puts it just about right: assuming one does not reject the modern age (including modern medical care!) entirely, and assuming one accepts at least the bare outline of Christian teachings about both the common good and the integrity of the individual, the question is not “will the final Democratic health care reform proposals involve socialism?” but just simply “what level of socialism should we have?” Consider a couple of thoughts on this basic question.

E.D. Kain, building off some things I’ve written before, makes the point that if you care about local community, what you’re likely really caring about is the individual and collective opportunity which the absence of centralization and monopolization makes possible…and that, therefore, you should probably be in favor–at least insofar as medical insurance goes–of some sort of national action to make “a national marketplace that is at once able to sustain large cost-sharing pools and also be highly competitive.” Erik and I likely disagree on many of the particulars of the proposals and compromises being discussed right now, but we seem to be on the same page when it comes to recognizing that localism is best understood as a defense of local places which makes other, more populist options available, and not necessarily a restriction to local places, as they can very easily imitate all the sins of larger polities. (Something I’ve discussed more here.) Why a national market? Because our economy is national; our society is national; large employers–and the insurance companies they join together with, those very insurance companies that, for better or worse, the Democrats have chosen to work with and build upon, rather than oppose–are national. This is not something that can be done on a state-by-state basis (though obviously further, more radical or challenging reforms could be).

Peter Lawler, who himself isn’t much of localist or populist, takes profound exception to this possibility, arguing, contra my own Christian Democratic sympathies, that “genuinely subsidiarity-minded Porchers [makin reference to Front Porch Republic there] should be the most extreme opponents of the Pelosi/Obama health care reforms,” and that “I’m all for subsidiarity as described by our philosopher-pope,” which is why he opposes “European cradle-to-grave dependence on government.” Two points of order here. First, how would the “Pelosi/Obama (what, Senator Harry Reid doesn’t get a shout-out?) health care reforms” creative “cradle-to-grave dependence on government”? As outlined above, we are dealing with a lousy situation when it comes to medical insurance, with the majority of insurance plans being tied to employment and being run like little monopolies; and moreover, we are looking at a potential set of reforms that doesn’t even go half-way towards making that lousy situation at all more reliable for most American citizens. This is not, in other words, a reform proposal that will result in hundreds of millions of Americans throwing themselves at the national government’s feet. Second, while I am no expert in Catholic writing or thinking, it seems to me that Pope Benedict has made it clear that subsidiarity must be conjoined with “the principle of solidarity” since the former without the latter will result in “social privatism” (Caritas in Veritate no. 58). I take this to be a re-iteration of the fundamental point of the commonweal which is served through the providing of subsiduum in the first place: as the whole society is bound more closely together and made more just through common actions of interpersonal aid, so should those attempting to find the right levels of aid–in health care, or in anything else I suppose–be open to the role that society-wide actions (which, in the United States today, means federal government actions) may play in fostering such. Not in replacing all other agencies and actors who do such fostering, of course, but merely in doing something. Like, say, in structuring some national, equitable, reliable insurance markets, perhaps.

I realize a lot of Catholics aren’t too impressed by Commonweal, considering a somewhat Catholic-lite magazine, but from this outsider’s perspective, J. Peter Nixon’s recent analysis of subsidiarity and the health care debate seemed persuasive to me:

In his 1991 encyclical Centesimus Annus, Pope John Paul II was critical of the tendency of the modern state to take on an ever-expanding range of functions to the detriment of private initiative. Pope Benedict echoed these criticisms of the “social-assistance state” in his recent encyclical Caritas in Veritate. Both encyclicals, however, also argue that the state must play a role in structuring markets so that the benefits of economic growth are equitably shared. The 2003 Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church attempted to summarize these key aspects of subsidiarity by noting that the principle must be understood in two senses, “negative” and “positive.” Negatively, the state should refrain from restricting the initiative, freedom, and responsibility of the smaller cells of society. Positively, the state should provide the necessary economic, institutional, and juridical assistance that allows these cells to flourish….The principle of subsidiarity reminds the state that its role is to support and sustain the institutions of civil society, not to replace them. Nevertheless, to the extent that threats to those institutions arise from the workings of the market, Catholic social teaching envisions an active role for the state in their defense….

Health-care reform will increase the role of the federal government principally in the areas of financing care for the uninsured and regulating the health-insurance market….[P]roviding insurance to those who are not well served by our employer-based system has long been a responsibility of the federal government. While some of this expansion in coverage will come from expanding public insurance programs like Medicaid, most will come from subsidizing employers and individuals so that they can purchase private coverage. The second way in which the federal role is likely to expand is in the area of insurance regulation….For the most part, these expansions of the federal government’s role in health care are designed specifically to address problems that lower levels of government have failed to solve. While the number of uninsured has been above the 40-million mark for more than two decades, very few states have been able to marshal the resources needed to extend coverage to this population. States have also faced a difficult time in reforming insurance laws to eliminate various types of coverage exclusions. [Thus the] case for a federal role in these areas is strong.

I am not the sort of progressive (assuming I am any sort of progressive–which I suppose I am, though a fairly odd one) who believes that the key to making our polity a more just, more community-minded one is to simply grant more power and more reach to the most powerful actor around, the federal government. There are many ways in which I think it ought to be–needs to be!–restrained and cut back. But here, in this rather particular matter of medical insurance, I don’t see it. Call it socialism, call it solidarity, call it subsidiarity, call it whatever you want: from my study of the proposals under debate–which, as I said at the start, is hardly expert, though I do my best–they are not programs which will doom all efforts to preserve local communities and popular democracy, or even force people necessarily to choose between those goods on the one hand and a more just and equitable providing of patented American-style complicated health coverage on the other. They are, instead, relatively legitimate “subsidiarian” efforts that will maybe, just maybe, make locality and democracy that much easier for ordinary people, with ordinary health concerns, to achieve.

“The very short answer is, blame Catholicism.”

I wish that your answer were correct, but I fear that, in fact, it is very far from the truth.

What the Congressional Democrats propose to do and what the social encyclicals teach may seem (seem, I emphasize) proximate, but in spirit, they are, I suspect, much opposed. At the very least, one must consider that the respective anthropologies proposed by liberalism and Catholicism are wholly different.

Of course, one could take a prudential view of the health-care scheme itself, but I’m very suspicious of any effort to pour holy water on what the Democrats are proposing.

Russell:

Thanks for your thoughtful comments about my essay and about the topic of subsidiarity and health care generally.

As to Commonweal, I’m not sure I agree that “a lot” of Catholics disagree with the magazine. The magazine has passionate supporters and equally passionate critics. But taken together, their numbers are a tiny fraction of the 70 million or so Catholics in the United States! On the Internet, the critics probably outnumber the supporters, but the reverse may well be true in the pews. In any case, like FPR, Commonweal is an extended, inter-generational conversation about the meaning of a tradition, one that has been going on for 85 years. I hope you keep reading.

God bless,

J. Peter Nixon

Peter, thanks for your kind comments. As I said, I thought your essay was a very persuasive piece of writing.

TN, I take your point (Catholic personalism is surely not the same as modern liberalism, with whole different ontologies of human being), but I think your criticism perhaps misunderstands the point of my essay slightly. I’m not arguing that the Democratic health care reform proposals are a good match for various papal encyclicals (in the end, I said that they were, at best, “relatively subsidiarian”); I’m saying that it is Catholic teachings that most firmly persuade me to see in these inevitably partial, half- or quarter-way proposed reforms at the national level something worth defending.

I firmly supported President Obama’s priority on health care reform, until I noticed that the bills emerging in Congress were big unwieldy bills which tried to put everything into one big package, and, were almost impossible to evaluate, because of all the nit-picking and generalizing by both supporters and critics. So, I find this analysis rather comforting. On the whole, it will be better to get something like what is now on the table passed, than to have the entire effort fail. There will, no doubt, be tinkering over the next several years, some of it good, and some of it bad. Like social security, it will be impossible to simply undo it.

It would have been better if a package of bills could have been developed, each subject to a separate review process and votes, in committee and on the floor, some of them moving faster than others perhaps. It would have been better if we could have scrapped the tangled mess we have now, and built something new from the ground up. But too many people, including those who are insured, are unwilling to let go of what they have, so something has to be cobbled together from what exists. Its messy, but it will be somewhat better.

I had no insurance until I was 51. I then had employer provided coverage for four years. I got three check-ups, identified one chronic but minor illness which had probably been building for a while, and had one minor outpatient surgery that I could have well survived without. I have had all kinds of scuffles by mail with medical providers and insurance companies. When I lost my job, I could have kept my coverage under COBRA, but it would have cost me $700 a month that I would have had difficult affording myself when I was making $13.00 an hour, and certainly couldn’t pay without it. There was a federal subsidy I might have qualified for, but, I couldn’t afford $235 a month without another job. I hope when I can afford it to obtain a high-deductible policy for about $250 a month, and put money into a health savings account, considering I don’t need either check-ups or surgery every year, and just want to be covered if I have appendicitis or something. I’m still not sure the current health care bill will provide for that, but I’m not sure it won’t.

Excellent read. I agree that the current effort is probably a first step and that we are likely to see continued efforts for the next few years. I also think scrapping the whole system and designing something rational would have been great – but completely impossible given the political environment.

I think the current bill (it is hard to be sure what exactly the current bill is) does provide an opportunity for local solutions in that it may encourage the development of medical insurance co-ops. While these could be local they are more likely to be specific to groups – there is I believe a religious denomination which currently operates one.

I think we must recognize that big government is not the only threat – big business is too and so it is necessary for the government to regulate those businesses so that the common good is served. The insurance companies – more so I think – than the banks – are the epitome of big business gone mad.

Russell – my comment “excellent read” was not worthy of your essay. So I shall add that it was a true pleasure to read a commentary on our current health care debate which spoke of compassion, the common good and our obligation to the poor. Subsidiairty is often a difficult concept to explain and you did a fine job.

Arben, do you think the Democrats in congress are going to write a ‘health care’ bill that works? Or do you think the final Democrat legislation will be so badly flawed that it will result in theft, the creation of wasteful bureaucracies, and American citizens either not getting the proper medical care or not getting that care in a timely manner?

Keeping in the tradition as the party of death (abortion laws and pro-euthanasia) Democrat ‘health care’ policy will result in the untimely deaths of many American citizens. I pray that those who will die because of gummint intent and ineptitude will not be members of our families.

I agree that ‘health care’ needs reformed. But common sense tells us that it will require a public discussion that should include BOTH political parties (and major independents), representative of the insurance business, tort reform, and, indeed, meaningful public participation. What we have now is legislation generated from the commie-Dem, socialist side of the aisle, without tort reform, which ostensibly empowers the central gummint…I don’t think, in the long run, you’re going to be happy with nationalized medicine.

And, while we’re at it, one more point. Dude, this is so not you; you are so much better than this that I’m surprised that you lower yourself to this puerile level: “In response to complaints (once again!) about “socialism” and health care, John trenchantly responded that “[i]n any community, there are obviously some services which need to be socialized,” adding that if “one is really opposed to socialism, then one ought not to pull that socialist lever in his home, the one that makes his waste disappear in a whirlpool into the socialized sewage treatment system.” I think that puts it just about right…”

Really, that’s your best response to my “socialist” carping? Come on Arben, you always provide a loquacious, sometimes insightful, response to my derisive comments but the above is just childish.

Unfortunately, I think, between nationalized ‘health care,’ cap and trade, and now efforts on the part of the commie-Dems to shut down what remains of American industry via EPA regulations on greenhouse/carbon emissions, we may be looking at revolution….we’ll see.

This naïveté frightens me.

“Maybe, just maybe” the State, in exchange for terrifying control over your life, will nurture civil society.

Why does everyone who writes about this subject start with the assumption that our “health care system” (as if anything so important can be reduced to a system) is broken and needs massive reform? The last I knew, about 80% of all Americans are happy with their health care. That is a majority way beyond any definition of majority we ever apply to any issue in our political life. Here’s the fact: we have the best medical care available to the most people than any polity in the history of mankind. Insofar as it has problems (gosh, imagine that–problems!) more of them are attributable to government interference than to lack of government supervision. In the current debate the attitude of localists should be, do nothing, be patient, obstruct any attempt to make ideological definitions of the best into enemies of the good.

Think of it this way. Any bill, about any subject, that is 2000 pages long cannot be good for anybody but those who want to exercise power. If we start from that perspective we don’t need to spend 2000 hours of intellectual effort picking nits over its almost infinite number of unintended consequences.

Russell Arben Fox, I appreciate the energy of your essay, but in the end does it say that we should do anything other than what the Obama/Reid/Pelosi trinity wants us to do?

I have an alternative proposal for our rulers to consider, and I am very serious about this. “Medical care, being important to the republic, should be available to all our citizens. To that end we shall encourage the increase in the number of institutions dedicated to the education of medical professionals by a factor of ten by the year 2015.”

Socialist, I get. Maybe even subsidiarity. But why taint a good, radical, anti-state word like solidarity with this massive bureaucratic nightmare?

I’m with Professor Willson on this one: the overwhelming majority of Americans, myself included, are more or less satisfied with our health care. Convincing people, again, myself included, that I need to pay a ton more in taxes so that I can get less health care while people I don’t know get more is going to be a prett tough sell, politically speaking.

There’s also a real question about whether the bills currently on the docket will accomplish anything even remotely like what their drafters claim to intend for them. I think one of the main reasons the Stupak Amendment has received such attention is that, aside from it being a political lightning rod issue, it’s one of the only provisions in the entire behemoth which will likely do what it’s supposed to do.

So I oppose the health care bills not because I think the system is okay–I know I pay way too much for health insurance–but because I think they’re all massively expensive boondoggles which will add to our already unsustainable fiscal situation without doing anything to justify the added expense.

What’s to like?

I’m watching this from the outside, but as I understand it, people aren’t complaining about the quality of their health care in the US, but about how much health insurance costs. A big part of the problem is how much every health service costs in the US. For you to visit your doctor and tell him where it hurts costs over twice what it costs for me to visit my Canadian doctor and tell him where it hurts, and contrary to popuar belief, it’s just as easy to do that here. And it’s like that for every single service. I don’t see where the bill really addresses that, which is why I’m skeptical that it will really do much good. Of course, probably just having insurance artifically inflates the cost since you’re not actually haggling about what you’ll pay; instead, your insurance company and the clinic are haggling about what you’ll be willing to pay over time, according to them.

The problem, as I understand it, is that health insurance premiums in the US have gone up, on average, by something like 138% in the last decade, or more than doubled. What this means is just that there are more uninsured people than there were ten years ago, and some states like Alaska or Maine are reaching about 30% uninsured- or the national average in Canada when the country went to a single payer system. The cost of health insurance is expected to continue going up over the next decade, even with no govt. involvement, and actually at a somewhat faster rate. Nobody that I know of is expecting the price of insurance to start dropping. So, it’s not inconcievable that the poorer states could reach 40-50% uninsured within a decade.

As I understand it, that’s what these people are hoping to address, although I’m skeptical that they’ll do so successfully.

Lots of good comments here.

Siarlys and Cecelia, thanks for sharing your experiences with us. Both of you are, I think, essentially correct in recognizing that if a national health care bill is signed into law, it’ll be much tinkered and experimented with, on the state and federal level, both backwards and forwards, in the years to come, and much–if not all–of the ultimate worth of its reforms will be played out in that tinkering. This huge bill does a few concrete things that I believe will be helpful, but ultimately it’s only an opening of a door to making all sorts of other options possible. In the end, I’m betting on those possibilities.

Bob, I actually do think (like such non-partisan groups as the Commonwealth Fund) that the current mess of proposals being discussed in Congress are likely to “work”: that is, they will address some of the injustices in how medical costs are totaled up and distributed, and do so without bankrupting us completely. Will any of them they “solve” the long-term problems which our medical insurance system(s) leave us with? No; costs are going to continue to go up, for reasons that have been well documented on this blog. But, as I just said, I do kind of believe that it’s worth trying to get a foot in the door towards broader reforms.

As for poaching John’s comment, I admit I wasn’t aware it was directed solely at you. (Was it?) And I guess I have to disagree with saying his comment was “puerile”; I actually thought in was quite on target. I don’t mean to be a jerk about this, and I hope I’m not coming off as such. Perhaps the casual way I invoke socialism in the context of the post was a facile, and I apologize for that. But then again, you can’t get around the fact that there are socialist programs on the one hand, and socialist principles on the other, and the two are not necessarily the same. State socialist programs have an abyssmal–and sometimes horrifying–track record; that’s for sure. But all state programs which betray certain “socialist” principles, on the other hand? Well, seriously, who built the roads you drove to church to on Sunday?

HappyAcres, whence cometh this “terrifying control” over my life? Empowering the federal government to prevent BlueCross BlueShield from refusing to insure a pregnant 30-year-old because she and her husband generated her “pre-existing condition” before she got her job? The bar for “terrifying control” has obviously been significantly lowered.

John, I don’t think our health care system(s) is “broken.” I think there are several things which it, systematically, does poorly or not at all, things which I would like to see done, or at least done better. Some of that, obviously, needs to involve local action. But some of it–namely, the goal of justly providing the opportunity for medical insurance to all–needs to involve some national action, for reasons I mention.

Caleb, as for the injection of “solidarity” into this argument…as I said, I blame Catholicism. They started it.

I agree with Willson that this farrago was hatched fully formed as a “crisis” and the words spoken by that classic rabid apparatchik Rahm Emanuel pretty much sums up the mindset of our Babylon on the Potomac. Early in the process, he asserted that the task at hand was to simply gain “any legislation” so that any problems might be resolved by “future legislative efforts”. In other words, it is not the subject at hand that is of primary concern, it is the continuing life of legislation that is. Legislation is, of course, the fuel to keep the infernal combustion engine of Foggy Bottom churning away. And just so there is no mistake, we can review the footage of Mr. Conyers scoffing at someone who had the temerity to suggest that they actually read the legislation before voting upon it.

The fact that we are led to believe that a Federal Solution…sorry for the oxymoron but….that a Federal Solution is required to solve such an important thing as our health “system” is just another example of how far gone we are as literate citizens of a Republic. We wait, and still, despite the sordid displays in Washington, our Governors remain silent and subservient to our Congress and in breathless thrall to the Executive.

To think that this current government, awash in debt and cant might arrive at an equitable solution for

the life of the people is the height of Blind Faith. Could a Federal Government, in concept, arrive at such a possibility? Certainly…..just not this one….of this our continuing appetite for further proof remains an object of simultaneous hilarity and dark , loathsome shock to me. Reason, like Elvis, has left the building.

Nicely put, D.W. In addition, we will be saddling our children and grandchildren with a huge, insupportable amount of debt. That this crew doesn’t care about the unborn is fairly obvious, but it has become quite apparent they care not a whit more about the not-yet-born.

In the long run we shall all be dead. Quite.

Rufus,

For you to visit your doctor and tell him where it hurts costs over twice what it costs for me to visit my Canadian doctor and tell him where it hurts, and contrary to popuar belief, it’s just as easy to do that here. And it’s like that for every single service. I don’t see where the bill really addresses that, which is why I’m skeptical that it will really do much good. Of course, probably just having insurance artifically inflates the cost since you’re not actually haggling about what you’ll pay; instead, your insurance company and the clinic are haggling about what you’ll be willing to pay over time, according to them.

Thanks for adding some Canuckistan perspective to the debate. You’re right, of course; while there are numerous professional number-crunchers spinning out all sorts of estimates, both for and against various proposals, that will total up the costs different ways, the essential problem is our insurance monopolies. They do what they are able to do because the United States, for reasons both intentional and unintentional, ended up limiting any response to the collective action problem of medical costs to the elderly (Medicare), veterans (the Veterans Administration), and a limited number of poor people (Medicaid); everyone else just has to scramble as they think best, and that generally means holding on tight to employer-based insurance plans (if they can get any), thus enabling those insurance companies to work out any number of restrictive pricing deals which serve their bottom-line, without fear of losing their subscribers, because the great majority of them can’t reasonably go anywhere else.

As I noted several times in my post, a truly radical, serious attack on this interrelated set of problems was never seriously considered by the powers that be in Washington. That left us with half-measures; namely, building on private insurance middle-men and their attendant regimes. John Médaille concluded that if you’re going to do that, you might as well go with a single-payer approach–which is what Canada has done, and I know it works pretty well (less costly and more flexible than our nest of insurance monopolies, at least). But of course, we didn’t even do that; what we have being debated in Washington is a mess of interretated quarter-measure, at best. Does that make it worth supporting? I think so, if only because–and this was really the point of my whole post–one of the problems (not the only one, and maybe not even the most important one, but a serious problem nonetheless) with medical insurance in America today is that it often made available inconsistently and unjustly and at too great a cost, and the national government can make a claim to being able to do something about that, in a way that states and cities cannot. Subsidiarity, in other words.

To be mocked by D.W. is painful, but it’s a good pain. My compliments, D.W. And your threw in an Elvis reference to boot! My cup runneth over.

RAF…I would never think to mock you, though I might mock an occasional opinion you voice. You forthrightly bring your statist voice here despite the near-anarchist brigands about and for that alone, you have my respect. The fact that Cheeks has a soft spot for your contributions adds another mark against you but we must all carry our sundry weights. Some of the ideas, well, we will keep Lundying them as they may arise.

Seeing that many U. S. states have larger populations than entire foreign countries that critics of U. S. health care would prefer (Cuba: 11 million people, Sweden: 9 mil, Norway: 5 mil), why do we need a national pool of people in order to have affordable health insurance?

Shouldn’t a localist–especially one who desires political and economic structures that encourage commitment to local areas and actively (for those who favor an active government) discourages meritocratic mobility–be committed to U. S. state-scale endeavors?

It seems that state-scale health care is eminently reasonable apart from the only “downside” which consists in difficulties that arise from moving constantly from state to different state. But I would think such an effect is, for those lovable folks sympathetic to the concerns of FPR, not such a bad thing.

I certainly agree with John Wilson’s point that the number of medical care training slots by a factor of 10. However, I don’t see how that can be done without massive gov’t action. The number of people with both the inclination and wealth or credit to obtain such expensive educations is likely already at its maximum. You would have to lower the cost (and likely improve high school and college education at the same time.) But increasing the number of licenses would lower their value, hence making the education even more expensive in relation to the expected rewards. This is a rock/hard place dilemma.

Nor do I agree with the claims that the system is working or that it is the best. In fact, most statistical measures rate US health care very low, despite the fact that we spend more, by far, than any other country. The reason we spend more is that every other country has some sort of price controls on the monopoly/oligopoly services and products. I believe such price controls are legitimate in the face of monopolies. If you want to eliminate price controls, then eliminate the monopolies that are the occasion for them. This is just econ 101.

At 17% of the economy, and rising, health care is just not sustainable. And providing health care through businesses, particularly small businesses, is an undue burden. We compete with countries were this is not really a concern for business.

As for the polls showing people satisfied, with their insurance, they only poll the insured.

RAF, I could not agree more with D.W. about your contributions. It seems that I respond to them more than to almost anybody else’s. That, back in the day, was a sign of respect. On FPR, I hope it still is.

Now, having said that, I still insist that somebody says what is broke so we can fix it. I’m sorry, but the Canadian (or Brit, or French, or German) model doesn’t work. It’s like immigration. Do we see huge numbers of Americans going to Canada for high-level care? One aspect of all this that is almost never discussed is that in EU countries their governments are even outlawing vitamins. The more we centralize this stuff (17% of the economy or not) the more we are going to be at the mercy of FDA bureaucrats and the biggest lobby in the history of the world, bigpharma.

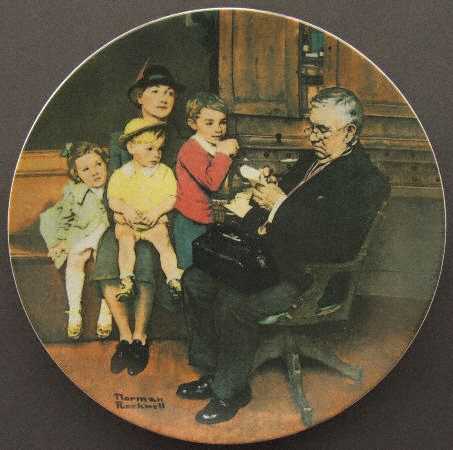

When my Dad was the Last Country Doctor there was nobody, not one, in our little town or county who did not have access to the best medical care that was available. I am not saying it was the best there was in the world, or the best that one can imagine (God save us from the best that one can imagine), but the freer the access is the better chance we have to do the good, even if it is not the best. If we had ten times the medical professionals that government will now allow, and fewer restrictions on the types of medicine that is allowed by the government supervisors, much of the cost and the ideology would go away.

Remember, the government does not care for the poor. The government builds bureaucracies that say they care for the poor, but the money goes into the hands of the bureaucrats. Letting doctors be doctors is the best way to approach all this.

John W., Yes, we do see huge numbers of Americans going to Canada, specifically to buy medicines.

I can’t keep up with who all I’m replying to. I already laid out why I’m NOT satisfied with my health care, when I had it, nor with having none, nor with the prospect of being fined money I don’t have if I don’t get insurance I can’t afford if I don’t have a job with an employer who provides it. MAYBE the subsidies will be adequate, but then, who is going to pay for the subsidies?

I do have a problem with how much medical care, and insurance, costs. Part of the cost problem is that there is so much shiny technology available, and we need some share of cost and individual responsibility to get that under control. The devil is in the details of defining “need” vs. “want,” without it being labeled “rationing,” or overwhelming individual choice. But doctors have to stop telling me what to do, and start offering my information on my options.

The best addition was breaking it down to the state level. This should be done within a federal framework that sets a floor, as they did with the Family Medical Leave Act. States may provide for additional rights, beyond what the federal law provides for. But if it is wide open, we know what national and international insurance companies will do: they will bully each state and threaten to take their marbles and go home if the state doesn’t give them whatever they want. I am really more afraid of soul-less insurance bureaucracies than I am of incompetent federal bureaucracies. I sought help with a recent problem from my state insurance commissioner, but because my employer is self-insured, using the insurance company as an agent, ERISA denied any state jurisdiction.

Another good addition was increasing the number of doctors. How about this: the federal government (us taxpayers, that is) will fund half your medical school program, if you agree to devote at least ten years post-residency to family or general practice, and ALL of your medical school program, if you agree to devote at least ten years post-residency to family or general practice in a severely underserved area. Those who want the more remunerative specialties can raise and repay their own costs. It would allow some crude free-market choices, and emphasize where we really need doctors: doing the everyday stuff that keeps us from needing the shiny technology so often. After ten years, a lot of docs will have sunk roots and really enjoy whatever community they are located in.

What has been missing in many crises in the past year is, if it is too big to fail, and too big to control, break it up!!! Just as they should have broken up AIG, selling off each healthy piece as a separate entity, then repaying taxpayers and shoving the losses to the parent company, the current health care financiers should be broken into smaller pieces. Any imbalance in risk pools could be smoothed out by allowing reinsurance at the national level.

I really hate to be a pest about this. But John, darnit, Americans don’t go to Canada for medical care, they go to buy drugs. Canadians subsidize our purchase of drugs that often come from the US in the first place. Canadians who need really good real medical care come here. Or they wait until some government flunkie tells them they are next on the queue. Americans who go elsewhere for MEDICAL care do it because they need to find a treatment or procedure that our, guess what, GOVERNMENT has proscribed.

And Siarlys, we really don’t have to subsidize anybody’s medical education (we already do, but we don’t have to). The medical professions are very attractive: They give men and women a chance to really help people, and do it in real time as opposed to deferred satisfaction, and they are one of the three traditional culminations of the liberal arts–the other two being theology and law.

Those who doctor to us do a sacred thing, and it cannot by definition be regulated, defined, or administered by governments. It can be helped–the University of Michigan Cancer Center has done great things for my wife, but I also remember sitting with my Dad when the announcement of the privately researched polio vaccine came on TV, and one of the most dreaded diseases in human history was eliminated. I also know that all the government help in the world has not done one thing to prevent heart attacks, despite what the statin manufacturers claim.

If we give in to the assumption that government has the power to make us happy we have given up every single thing that I hope FPR stands for. End of sermon.

For John W.

1. Getting prescription drugs is getting health care.

2. Americans don’t go to Canada for other services because they aren’t provided for Americans, and their insurance likely won’t pay for it.

3. The Canadian government does not subsidize the purchase of drugs by Americans. They control the monopoly prices, which is what every other civilized country does. It is, indeed, what one ought to do with monopolies, merely on the basis of sound economics.

4. Canadians do not come to America for health care; rich Canadians do, which proves we have the best system in the world for the wealthy.

5. Or maybe not. Americans go to India for expensive operations, which proves (by your logic) that India has a better health care system than the United States.

6. Your statement that what doctors do “cannot by definition be regulated, defined, or administered by governments” is simply wrong on an empirical basis. Cf the Veterans Administration, the FDA, medical licenses, etc., etc.

7. Actually, government has done more than one thing to prevent heart attacks, mainly by attacking smokers like me, and getting most of us to quit or taxing us to the point of extinction. I defeat them by rolling my own from pipe tobacco (the tax on cigarette tobacco is $25/pound; on pipe tobacco it is $2/pound), but this is a Pyrrhic victory, to say the least.

8. True, govmint cannot make us happy, but I don’t that we can be happy without a functioning government. I am a localist, not an anarchist. Man is a social, nay, a political being.

Ahhh yes, a “functioning government”…..where might that chimera be? It aint in Washington and our Statehouses think they are simply counties of a Federal District now so just where might we find it? Shall they spring out of our efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan? No? Then where? I’d really like to know because i am beginning to think it is like hunting snipe….some kind of activity for the locals to send the hicks on for laughs.

Sure , man is a social and consequently political animal but this current government is a dada abstract rendering of what we think political organization should be. It is well around the bend and going farther as we speak.

As to Medailles comment # 6, perhaps in the abstract, government “regulates” medical care such as in the areas you cite but I believe Mr. Willson was referring to the more non-regulatable aspects of a Doctor or Nurses duties…that human thing governments think they should or could regulate but never do…frequently mucking things up good when they try.

I am put in mind of the status of doctors and lawyers in my youth…..they were the wealth class, the local leaders…doing real work and being paid handsomely for their skill, hence their investment in local real estate and a host of other local areas. No more, they have been eclipsed by the freebooting wealth class, a class that is increasingly centralized in a few locations, makes its money on intangible and , in some cases, wholly artificial things that leave nothing of tangible worth behind in a community sense. Doctors and lawyers make chump change now…..in comparison. This is obviously a generalization and has its exceptions but in the major, it is the result of the last 50 years of economic dysfunction facilitated by a State we now ask for help from concerning our health.

We should be far less concerned about our Health System than we are the fundamental gutted economy we have slouched into because we cannot now pay for the health system we think we need because the fundamental debauched economy will not tote the load. We could do it the semi-easy way but will no doubt allow conditions to deteriorate to such an extent that the hard way will require a new and updated definition of “hard” in order that we might fathom it.

As to cross border subsidies, I think the American consumer effectively subsidizes the Price Controls of the Canadian Government……..again, we have a host of perverse relationships in our collective economies, neither free market nor state-monopolized….too frequently, we are arriving at the worst hybrid and wondering why things continue to ditch.

Bridgeport , Connecticut, once again, a good example of the problem we face . The “Made In Bridgeport” exhibit at the Barnum Museum…a gleaming pyramid of all the consumer products made in America that once kept the “Park City’s factories humming (and admittedly, its harbor and rivers polluted). No more, and the Park City is anything but a park and it has some of the lowest levels of service and highest taxes in the State and get this….as I understand it, 50% of its taxable property is “non-profit”. The fate of the nation is the same as Bridgeport’s if we do not stop approaching our problems in the same idiotic manner. To have a healthy medical system, we need a healthy economy where people are productively engaged. Thinking we can have a healthy medical system on top of a failing economic and federalized paradigm is a pig in a poke without an antiseptic. It is another dodge whose unexpressed result is the continuing enrichment of those who freeboot for a living in the Imperial Seat. You want “Isolation”? Look at Washington D.C…..it is “isolated”.

Medaille, the fact that you handroll pipe tobacco to avoid cigarette tobacco taxes and wear a black cowboy hat while visiting the shtetls of Romania , despite whatever disagreements there may be between us, well…..these kinds of things give you points…..to a point. Pipe Tobacco Handrolls, why I reckon I never.

DW’s comments put me in mind of Milton Friedman’s quip that “If the government were in charge of the Sahara, there would soon be a shortage of sand.” It is a clever comment, but to make it he had to rise in the morning in his Chicago apartment, built no doubt to exacting government codes, wash in water delivered by a socialized system that guarantees its purity, and not to be confused with the socialized system that carried away his morning waste. His breakfast was the result of a food system monitored by a vast bureaucracy, and he traveled to the airport on city streets and federal highways. There he boarded a plane that was built and inspected to government standards and entered an air traffic system that is a marvel of government planning. On landing safely, he was conducted to a university supported by public funds where he delivered his clever comment at a conference that might have been supported by a government grant. And after the conference, he met with friends at a good restaurant–inspected by government officials–to revel in the sheer wit of his comment.

Friedman for me epitomizes that attitude of ingratitude which characterizes my generation, easily the worst generation in the history of our republic. Our finely tuned sense of entitlement did not involve that sense of responsibility which moves a man to pay for any of the services he uses; we demanded taxes be cut, but not our benefits. We live in homes whose amenities where unavailable to kings (The Palace of Versailles: 3,000 rooms and no toilets), protected by well-paid police, fire, and ambulance services.

I yield to no one in despising a government that has become gargantuan and corrupt. But I think Friedman’s attitude is that of the mere poseur who takes benefits to himself without end, but despises the source of those benefits. I believe that the country is no longer governable, which should be a boon to those who hate the government because it is the government; they will at least be in the best position to appreciate the joys of anarchy, but I do wonder if they will remember just how to make an outhouse.

The proper response to bad government is not no government, which is the worst government of all.

The proper response to bad government is not no government

Somebody needs to put this on a bumper sticker.

Perhaps, but I’ll take less government at the cost of the benefits I’m supposedly getting (Social Security?).

Mr. Medaille, I find it a curious argument to suggest that the use of certain socialized services renders a critic of socialism ungrateful for such services. Surely the means can be criticized without denying the goodness of the ends without rendering a man a hypocrite or ungrateful, unless one imagines that such goods are impossible except for the precise manner in which they were produced?

Mr. Medaille’s argument is akin to telling the person worried about air pollution to quit breathing.

… but he is correct about his generation!

My my, a tart rejoinder, nothing less is always expected…it is a long jump from consistent comments against this government to an accusation of championing no government at all. Poseur is it? And this from a cooperative/collective partisan in a businessman’s suit, wearing a cowboy hat. But, I’ll take it because to a degree, you are right…but only in degree and not in total as you might like to render it to prove your point. Make no mistake, I consider the species far too craven , jealous , venal and feckless…in summary: fallen….. to manage no government at all…as much sordid fun as it might be. But the idea of it, as a check on the current excesses, rather than as the asserted act of a poseur, selfishly riding the benefits is where I come from. Here we go again, lining ourselves up in the obligatory camps while placing the perceived opponent as far away as possible because the opponent has value to the partisan.

As you know John, in the past, I have thrown my hat (a straw porkpie) into the ring of subsidiarity and wish to stick to it, on principle, rather than , like a poseur, expecting it to somehow come after we refine it from the slap happy gig we now hop around to. Reform to a right ordered system from the current deadly laughing-stock, in an orderly and gradual manner is a pipe dream. Should we go backwards to go forward rightly or blindly forward into a bass-ackwards denouement?

Do you really think this current government will devise a Health System that is considerate of the citizens interests first and special corporate interests second? I’d be humbly cheered if the citizen’s interests made it into the top 5.

The proper response to bad government is not more of the same, which is a bad government, continually getting worse.

And…just to keep things interesting, I defend some of my earlier claims from attacks from the left of me, here. Enjoy, everyone!

DW’s a “poseur,” ha,ha,ha!

Now this is an excellent thread and that’s as pissed as I’ve seen our beloved Connecticut leaf-hopper!

I told you, the guy lives in a parallel universe, though I do have to tip my hat over his pipe tobacco purchase, while rolling his own…that is beautiful and caused my eyes to tear up.

Arben, I couldn’t get to the site you provided and I’ll try later. I do want to read Leftists “attacking” you??? Never-the-less “socialist succotash” is “socialist succotash!”

Albert, I don’t think the use of socialized services renders one incapable of critiquing socialism; one must live in the world that is, not in the world one might want. But since one does live in that world, one must acknowledge what one receives from it. I have received extraordinary gifts, and my critique of the social structures that provide the gifts would be disingenuous without also acknowledging that I have have received them. After all, the ability to take a hot shower in the morning is a gift unknown to most of the world and to most of history. You may not agree that Friedman, who derived much of his fame and income from government and government-sponsored institutions, is a poseur for failing to acknowledge the gifts, but I think he is vulnerable to such a critique by such a failure. His quip is legitimate in itself, but not by itself; it cannot stand alone without being subject to the charge of hypocrisy.

As for those who wish to handle the question by attacking hats, I leave that discussion to them; I am more interested is what is under the hat.

John M., I wear a Stormy Kromer hat myself, and what’s under it would not misinterpret what I said with points like your #s 1,5,6,and 8 above. There’s no point in going all the way back through them, but two things must be said. In point #6, by citing the FDA, etc. you are underscoring what I said in the first place. By politicizing parts of the medical professions that are not capable of regulation (only capable of making them political), government does for medicine what “marriage licenses” do for homosexuals. There are just some things that government is not only not capable of doing, but absolutely screws up the created order by trying to do. And #8 is just a straw man. It is not helpful to try to pass off serious questions by implying that I’m an anarchist, which, by the way, would set thousands of my students into peals of laughter. My father-in-law, by the way smoked Camels (real cigarettes) from the age of eight until he was sixty-four. He quit when they went to a dollar a pack. “A buck a pack for smokes?” he said. “That’s ridiculous.” I think he’s the only guy I’ve known who wouldn’t give in to a sin tax. He wore John Deere hats.

John, you obviously mean something very intelligent by “politicizing parts of the medical profession,” only I’m not intelligent enough to understand what you mean. I suspect it arises out of personal contact with a doctor in the family, experiences I do not share. I don’t know the specific things to which you refer, so I can’t judge them. But a statement that implies the government has no place in a profession it licenses and funds strikes me as odd, to say the least.

OK, this is constructive. There are several ways to think about any real profession, just as there are about crafts. A good finish carpenter can tell you how to put an old window sill together, but the moment a bureaucrat gets control of a window sill code, believe me, it will not improve the quality, cost, or appearance of window sills. It simply transfers power to whoever writes and enforces the code. So far, really simple. Now, what is medical care? First, it is one of the oldest and most important professions. It requires knowledge, judgment, empathy, and a high level of moral honesty. Which of these things can government control, regulate, or codify? Here is a specific example. In the licensed, drug controlled, government regulated “mainstream” medical profession almost nobody knows much about thyroid problems. They aren’t sexy enough to engage serious interest. In the holistic medical area there are several really good treatments available, and professionals who actually know what they are talking about. Guess who has FDA approval? Guess who gets persecuted? Guess which path is easier and more lucrative to take? How then, do we improve the research, judgment, care, technology, and moral concern about thyroid problems? The answer, I think, is not with government. It really doesn’t take much research to find out that government science is more often junk science than the freer alternatives. Don’t get me at all wrong, the government-sponsored medicine at, say, the University of Michigan is often very wonderful. But with a blank check and monopolistic control as this present “health care” legislation will give the government, you will soon not only not be able to roll your own, you will be put way down the list of people to get care for what damage you “caused” yourself. I don’t mind prudential attempts to try to make sure there are no poisons in Tylenol tablets (unlike the poisons in our drinking water, flouride and chlorine–by law), but the current debate is way out of hand. We are not talking about health, we are talking about control.

Its taken me a while to get the measure of John Medaille, but he is the most sensible person commenting here. I think I’ve already said somewhere that I would like to see a political platform emerge in this country which is

1) Culturally conservative.

2) Politically libertarian.

3) Economically socialist — when it comes to large institutions.

That leaves plenty of overlap and contradiction to work out, such as yeah, gays can do what they like in the privacy of their own home, like the Supreme Court said they can, now get whatever that is out of my face and out of these phony education programs for kids who don’t need it shoved in their face.

http://aleksandreia.wordpress.com

ought to show you a longer rant on that subject. Rod Dreher has hit it twice in the past week also.

There are some operations so large that no individual citizen can take care of it for themselves. Urban water systems and sewage systems are two of them. Delivering good quality, skilled, medical care, with a human touch and sound judgment, is not. But organizing risk pools for medical insurance is. And that is where the boundary between what rightfully should be socialized, and what rightfully the government should keep its nose out of, has to be sorted out on medical care. It is a beautiful vision that we should have local doctors taking care of local families whom they know well, being among the most respected of community leaders. I had such a pediatrician as a child — he even made house calls. We went over to his house for Thanksgiving. But the private sector and the monopoly un-free market aren’t providing that. They’ve robbed us of it. We could get some benefit off of subsidizing medical care, to help doctors afford to start out in markets where they won’t make as much money, but they won’t have such big loans to pay off, and in the long run, the cost of medical care will go down.

My beef is not with government per se. It is with the kind of “experts” who gravitate to government jobs, and think it is their sacred mission to find “the best” policy for everyone on all things, preferably one size fits all, and cram it down our throats. Government can set some broad incentives and policies, and set boundaries around monopolies, but then real live people have to grapple with what works best, for each question, in each local area.

I don’t expect the current health care bill to be really good, but that is because we have so many factions fighting blindly for issues right in front of their nose. It is also because, after a rousing campaign, our president is too afraid of being called a “socialist” to take the kind of bold action that would get us a half-way decent health care bill. I’ve had my years thinking we would be better off if we could just knock over the government we have because it is so dysfunctional, but in a society as complex as ours, we’d have cannibalism within five years, and when it was all over, we would NOT be the greatest power on earth, we’d be a client of the rising powers: Brazil, China, India, perhaps Iran, probably Russia. I wouldn’t call DW a poseur, but Friedman always was, for precisely the reasons John offered. He didn’t have a viable plan for free market meat inspection, or free market sewage disposal.

We are not paying the price for fifty years of government regulation. Government regulation just saved us from another Great Depression. Who says so? My mother – she lived through the last one, and she was a Republican until she say her beloved party running up the national debt by leaps and bounds, while a Democrat actually paid it down a little in between. (Reagan proved deficits don’t matter… yeah, right.) We are paying the price for a philosophy of smaller government, advanced in such a manner that large monopolies run amuck and trample all the rest of us… which is not exactly how we get back to the old Republic.

Arben has a decent idea for a bumper sticker, but if I produce one anytime soon its going to read I SUPPORT PRESIDENT OBAMA AND OUR TROOPS.

Oh, its the FDA you object to. Okay, but isn’t that a different set of issues? I mean there are arguments for an unregulated drug system, but there is also experience with it, an experience which is not very good. During the 19th and early 20th century, the medical profession peddled the snake-oil du jour. Granted, snake-oil may have just been elevated to a higher (and more expensive)level, but the medical profession has little to reproach the gov’t with on this score.

And can doctors really get prosecuted for prescribing a medicine that is not on the FDA list? If a doctor tells you to get some rest and slurp some chicken soup, can they be fined?

Siarlys,

There are some operations so large that no individual citizen can take care of it for themselves….Delivering good quality, skilled, medical care, with a human touch and sound judgment, is not [one of them]. But organizing risk pools for medical insurance is. And that is where the boundary between what rightfully should be socialized, and what rightfully the government should keep its nose out of, has to be sorted out on medical care.

Thank you for your valiant (but, I fear, probably in vain) attempt to reiterate the point that I made in the original post: actual health care–-the actual doctor or midwife or nurse examining you, healing you, offering you succor and relief–-needs to be and ought to be as local and face-to-face as possible. But can medical insurance be similarly local? Until and unless we have the political capacity to destroy the whole system of employer-based private insurance monopolies, no, it cannot–not, I think, if you care about the kind of justice which Catholic teachings call us to, at least.

Somehow, in all the often panicky back-and-forth over “government control” and whatnot, the real-world, practical limitations of the actual topic under discussion gets lost.

I have some personal experience with what John Willson is talking about:

I have a very mild thyroid problem. It was diagnosed by a family practitioner, I was referred to a competent endocrinologist. He didn’t get to know me real well, because he is part of a large network (created by the free market, God help us), and he had a large workload, within the framework of a bureaucratized office. But, he was competent, he prescribed an appropriate FDA-approved suppressant, he reduced the dose when my symptoms indicated he should, and I learned enough to monitor myself without further lab tests, office visits, and other costs. Good thing, because I am now uninsured again. Now, what is the terrible problem for treating thyroid problems which afflicts our under-socialized medical system?

On to home repairs. I am competent to do plaster restoration. I do it much better than many amateurish home repairs I have seen. I leave a smooth wall — you can’t tell where the hole was. I would like to supplement my income by offering to do this minor repair, without the hassle of licensing and inspection. I think I probably can get away with that, by mutual consent, whatever the letter of the law may be. Ditto for minor window repairs, like hanging the lead weights when the ropes break, or putting fresh putty on to hold the glass in the frame. However, if it comes to tearing down walls, re-sheetrocking an entire room, or installing a whole new window frame, I would want to know that I way paying a licensed, trained, certified, repairman, who knew what they were doing, could and would, and would be required to, do the job over if they botched it, and had insurance to pay my losses if necessary.

I have a friend in another city, who I once rented from, who had work done on his foundation by an incompetent fool, someone he met at church, a terrible way to pick a building contractor. Now, winter is coming on, the basement is wide open to the elements, the gas is turned off, and the guy says “Oh, I ran out of money, you want me to finish the job, you have to pay more.” Too bad he didn’t get a licensed contractor, with insurance and bonding. He could sue, but a lawyer wants a $10,000 retainer — understandable for the work this case would require, but he doesn’t have it. Exhausted his equity borrowing to get the repair done in the first place!

So, like I’ve said, as have others, including Arben, there is a place for government regulation and standards. Sometimes it really can protect us. The important point is, don’t sweat the small stuff. Leave us some room around the edges.

Now when it comes to the FDA, we have a different margin. Two of them. Protection from snake oil salesmen and their cousins who merely water down otherwise legitimate substances, so the dose is wrong, I’m happy to have protection from. But then, there are the people who take drugs for non-medical reasons. Prohibition has been a failure. We need regulation of prescription drugs, isolation but not prohibition of recreational drug use (I don’t want people shooting up outside an elementary school, but I want it to be cheap for those who insist on using it — so the drug gangs can’t afford automatic weapons anymore), and some room for people with terminal or painful illnesses to try experimental drugs when nothing else is working. True, bureaucrats aren’t good at writing regulations that way. But that is why we need to work for, not putting all regulation out of business.

Siarlys, that is true, but why must all non-individualistic enterprises be government enterprises? As soon as you bring in the State and its regulations, policies and laws, you are using the Sword to physically coerce fellow citizens and neighbors to do things they do not believe is best instead of persuading them (for if persuasion is used, voluntary communities would be sufficient). You force your neighbors to obey against their will or be thrown in jail. Why is it so easy for people to do this to their neighbors? Perhaps it is because people do not know their neighbors anymore and see them (and citizens across the country) in practice as mere inhuman statistics/tools/sources of money to achieve material goals.

There is nothing stopping people and scientists from voluntarily forming a non-governmental equivalent of the FDA, for example, that develops a reputation for doing good work and lives on the basis of trust. People listen to the NYTimes, Fox News, Google blog, RA Fox, local financial advisers, Warren Buffett, Wired magazine, Slashdot, etc. as cultural authorities and none of them require the kind of government oversight the FDA represents. Why must our only communities of authority be government entities? The State has a place by virtue of its legitimate wielding of coercive violence, but shouldn’t we limit its jurisdiction on the basis of the nature of its power?

Fine. But the government consists in the very same kinds of people as those in the private sector. They’re all just people formed in the same culture. The difference is that those in government are there because they desired the particular power of the State. Why do you think better outcomes will come from the government? People are people. But people without swords are generally less dangerous than those with swords, especially if those with swords believe all that they do really helps your neighbor, even against his will.

Albert, bravo!

I do hope you’re teaching somewhere!

I generally don’t like for anybody to tell me what to do, and I hate parking tickets as much as the next guy. But I cannot picture that a sewer system will ever be developed as a private, voluntary, cooperative enterprise, where everyone volunteers their time and money, and no cantankerous old jerk insists that he is darn well going to stink up the neighborhood with an outhouse. Further, I know that a large number of landlords are going to refuse to spend the money to keep their property up to code, and their tenants don’t have the hammer to make them do so. And the last thing I want to entrust my health to is a private, for-profit Food And Drug Certification Inc. — “you have… My Word On It.” Sorry, there are some things government has to do, no matter how incompetently. I think better outcomes come from government because, sometimes, they do. In any historical situation where there was NO government, the result was not happy egalitarian cooperatives, but some gang of bullies taking control. True, that is how The State began. It was an afterthought for ruthless conquerors who proved they were bigger bullies than anyone else, like Edward I and Hammurabi, to play at developing codes of law once their thrones were secure. But republics are built on the ruins of the thrones of kings, not on the original anarchy that preceded them. Anarchy leads to monarchy and dictatorship, not to freedom and prosperity.

Siarlys, so you would throw that “cantankerous old jerk” in jail because he uses an outhouse and you don’t like it? Would you do that to your mother or father or brother or sister or son or daughter? Really? Or would you just do that to an unknown statistic, a non-human entity that causes smells like a rotting piece of carcass?

I agree that anarchy leads to monarchy and dictatorship, which is why I never suggested it. I do suggest a test of “what would we throw a person in jail/punish for” whenever we suggest a government-enforced, taxpayer-financed scheme.

And my contention is simply that what you would throw a friend and neighbor in jail for disagreeing with you says a lot about you. And if you don’t even think about these statecraft issues in terms of how you deal with neighbors you have differences with, then I would suggest that you do in practice view your neighbors more like non-human objects rather than persons.

Actually Albert, I would have the city in which I live construct a sewer system, and hook up every house to it, whether the cantankerous old jerk wanted to be part of it or not. Sending him to jail would not arise as a question, unless he happened to shoot at the construction crews. But, this is already standard in most cities, so that wouldn’t arise as a question either. If he were, as described, my neighbor, he would not be a mere cipher or statistic.

IF hooking up to sewers were optional, I would measure whether to threaten him with arrest and imprisonment based on whether his personal choices infringed on his neighbors in the form of persistent odors or more substantial sanitation problems, illness, etc., and if he refused to clean up his act.

I believe that building and other codes should be flexible enough to allow, e.g., for someone who invests in a reliable, proven alternate technology, such as models of composting toilets which actually hold the waste and generate clean, sterile, odorless fertilizer, which can periodically be scattered around the roses. At heat and humidity found in the Amazon basin, animal waste disappears in half an hour. But in a densely populated area, particularly in a more temperate climate, even many rural areas, sanitation can’t be “everyone roll your own.” The more sparse the population, the more freedom you can exercise without giving your neighbors reason to complain. The more crowded we are, the more regulated we will be. On the other hand, if you are way out in the boonies, a tribe of nomadic raiders could do you in before anyone knew to come help you, much less dial 911. There are trade-offs for every choice.

Siarlys, would you also consider a State-enforced ban on smelly apartments? People in apartments live really close to each other.

How about really bad foot odors that can be smelled from across the hall or in a public space? Bad breath?

What if someone is really ugly and disfigured, repulsive even, for a majority of people who would rather smell body odor than have that visage revealed in public space?

Would a ban on those things, in principle, be a legitimate use of State force? They’d first be warned, of course, to clean up their act.

Albert, you may have noticed that everyone else has left the party and gone to bed, apparently yawning at the silliness this has degenerated to. Despite the wise admonition “Never argue with a fool, people might not be able to tell the difference,” I will make a brief attempt to respond sensibly to your foolish questions. After that, if I say no more, I have just explained why.