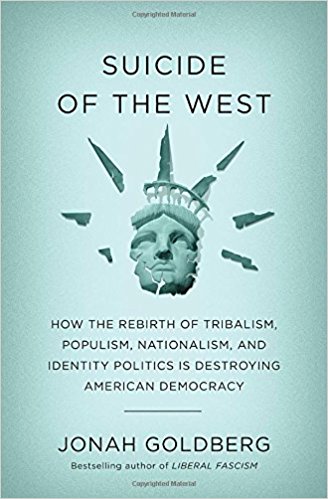

Jonah Goldberg’s Suicide of the West: How the Rebirth of Tribalism, Populism, Nationalism, and Identity Politics is Destroying American Democracy, appearing on Amazon and New York Times bestseller lists, represents a publishing triumph. The book has attained critical success with Yuval Levin calling the work a “conservative classic” and John Podhoretz hailing it “the book of the year.” For those such as myself who are fans of Goldberg’s writing and his excellent podcast the book was eagerly anticipated. It is thus disappointing to find that the book fails to meet expectations or live up to the hagiographic reviews.

Goldberg wishes to tell the tale of the explosive rise in political liberty and material prosperity that starts in the 18th century and to which we owe so much of our present prosperity. Goldberg believes, with some justice, that this material prosperity is the cause of the joint revolutions of liberalism and capitalism, especially as propounded by John Locke. These revolutions produced what Goldberg terms “the Miracle” of wealth and liberty. Our lack of gratitude threatens to undermine the Miracle.

Goldberg’s account is what Charles Taylor calls a “subtraction story.” Once the world was superstitious, ignorant, brutish—one might say “dark.” Around the 17th century new thinking arose that rejected the benighted past and suddenly there was Enlightenment. Subtract the ignorance–especially religious ignorance—that prevailed in the past and we can finally achieve liberty and prosperity. In his review Yuval Levin claims that the Miracle is “rooted in the traditions of the West.” But in fact the book has little good to say about any pre-Enlightenment event or idea. In the rare moments ancient Greek or Medieval Christian thought is mentioned they are denounced. Goldberg really seems to believe that the “Lockean principle of treating everyone human as equal in the eyes of God and government, heedless of who their parents or ancestors were, broke the chains of tyranny more profoundly and lastingly than any other idea.” No one with a passing knowledge of Christianity could honestly make such a claim (just note Galatians 3:28).

He is fond of the word “primitive,” which seems to describe nearly everything before 1688.

Clearly influenced by social biology, Goldberg’s account of the human person is hopelessly reductionist. One of his central claims is that democracy and capitalism are unnatural. Comparing human society to that of ants, Goldberg argues that both “organize around a centralized authority.” Humans, like “any random group of dogs,” will form packs or society. Human nature is a “termite” that eats away at a culture. He is fond of the word “primitive,” which seems to describe nearly everything before 1688. Goldberg believes that human nature is essentially that of the children in Lord of the Flies as “children are always closer to our natural state than adults.”

While Goldberg expresses contempt for Rousseauean romanticism, he implicitly agrees with Rousseau that culture represents corruption of nature. He just thinks it’s a beneficial corruption. He rejects the Aristotelian notion that while the polis comes into being for the sake of mere life, it has as its end the good life. Aristotle argued that humans are the animal for whom convention is natural, i.e., that we become most fully who we are only when cultivated within society. Goldberg believes we are most human when we are at our most base, asserting for example that both rape and adultery are “natural.” With his reductionist, bestial view of human nature, Goldberg thinks all that is good in human culture is “unnatural” rather than expressing man’s higher natural ends. In denouncing identity politics, Goldberg claims such politics only make sense “if you start from the romantic premise that traditional civilization is retrograde and oppressive and therefore those who want no part of it are oppressed.” Yet the notion that “traditional civilization” is “retrograde” is precisely the argument of the first half of the book. For Goldberg there is nothing natural in a yearning for beauty, for love, for God.

This might explain the antipathy towards religion that pervades the book. After all, the central trope of the book is a Miracle, and Goldberg is at pains to note that this miracle is entirely man-made. The work’s very first line declares, “There is no God in this book.” While he claims that this is simply a rhetorical stance to avoid messy religious disputes, throughout the book Goldberg’s reductionism undermines religion, especially Catholicism. He claims, “There is some reason to believe that religion itself is an evolutionary adaptation” with religion being one of “countless fictions agreed upon.” He calls “We are all children of God” a mere “endearing platitude.” God and the papacy, it is heavily implied, are manifestations of a primal desire for an “alpha ape.” He argues, citing Charles C. W. Cooke, that supplanting of Catholicism was necessary for the Miracle. He pardons British Whig anti-Catholic bigotry because it furthered said Miracle. Most alarmingly, Goldberg compares England in the 1680s to Europe of the 1930s in that both were periods where it seemed “tyranny…was the wave of the future.” The tyranny of the 1680s was James II’s Catholicism, implying that Catholicism and Fascism/Nazism are kindred threats to liberalism. To be fair, I doubt Goldberg actually believes this, but his writing leaves the inference easy to make.

If there is a saint in the book, it is John Locke. At various points Goldberg expounds the notion that “the individual is sovereign.” Goldberg notes Locke rejects original sin and “moved politics from a God-centered universe to a man-centered universe.” While he laments the decline in civil society, Goldberg opines that “the fundamental unit of our constitutional order is not the group but the individual.” Goldberg frets about our increasing “atomism” while being resigned to the notion that the good of individual sovereignty means “we have weaker attachments to any specific identity, but that is the price we pay for peace and freedom.” He promotes America as the place of “entrepreneurialism of the self.” Only belatedly does he admit “by removing the idea of external authority like never before and exalting the sovereignty of the personal, we have opened a door for human nature to come rushing back in.” Given his praise of “individual conscience” and “the sovereignty of the individual” it isn’t clear whether removal of “external authority” is a good or a bad thing for Goldberg. He strongly implies that human life is without purpose. Because he is so intent in arguing against a Whig/Progressive view of history, he sees it as necessary to explicitly reject teleology. We “want to believe” that “there’s a point to our personal lives.” But apparently history, and our lives, are just “one damn thing after another.”

Almost the entire work is given over to a reductionist, materialist, autonomous individualist view of humanity and society.

And herein lies the central problem of the book. Almost the entire work is given over to a reductionist, materialist, autonomous individualist view of humanity and society. Only in the last pages of the book does Goldberg lament a decline in civil society, family, and religion. Yet this decline is a direct result of the book’s principal commitments. Goldberg writes, “It is the family that literally civilizes us. Before we are born into a community, a faith, a class, or a nation, we are born into a family, and how the family shapes us largely determines who we are.” But both Lockean liberalism and the reductionist science that dominate over half the book reject this notion. Locke explicitly rejects both religious and familial authority. Goldberg belatedly speaks of reverence for “old institutions,” including the Catholic Church which was the nemesis of the first half of the book, neglecting to note that the Enlightenment thinking upon which he heaps praise unequivocally rejects old institutions.

Goldberg agonizes over the rise in nationalism, failing to note, as per Benedict Anderson, that nationalism is precisely a modern phenomenon that arises as a kind of new religion to provide the unity that post-Reformation Christianity could not. It is not an accident that, as Goldberg himself notes, modern notions of religious liberty coincide with the Peace of Westphalia and the rise of the nation-state. As William Cavanaugh has shown, modern religious “liberty” is really more about a “migration of the holy” to the nation-state than about creating an actual sphere of liberty in which religion can bear fruit. The lamentations of Goldberg’s subtitle, as Patrick Deneen’s recent book argues, are not in spite of liberalism but because of it.

It says a lot about a book ostensibly concerned with threats to American democracy that it cites Game of Thrones more than Alexis de Tocqueville. Tocqueville is too friendly to liberal democracy to be naïve regarding liberal democracy. The threats to democracy do not come from primitive urges or “ancient ideas,” argues Tocqueville, but from within democracy itself. Democracy by nature sunders man from his fellows. In one of his few citations of Tocqueville, Goldberg quotes Tocqueville’s quip that the American is “the Englishman left to himself.” It’s not clear Tocqueville means this as a compliment. Tocqueville admired the English in part because English aristocracy provided an order and meaning that American democracy could not.

Democratic man, liberated from all “external authority,” is alone and insecure. He will reach for any flotation to help him as he drifts at sea. Class and religion not being available, he will reach elsewhere. The threat of the “tyranny of the majority” for which Tocqueville is well known exists precisely because the individual fancies himself the arbiter of all things. If no one is lesser than I am, also no one is greater. Therefore the authority of democracy is the authority of numbers, as that opinion which has the most adherents is considered the best. The populism that rightly concerns Goldberg is not a pathogen external to democracy, but a cancer that arises from within.

Goldberg chides the French revolutionaries who “believed in the perfectibility of man.” Tocqueville, however, contends that Americans believe the same. Tocqueville terms it the belief in “the indefinite perfectibility of man” in a chapter conspicuously located at the end of a discussion of American religion. Emancipation from old modes and orders induces Americans toward the “impious” notion that anything is permissible. The notion that everything is permissible, which Tocqueville sees as the heart of tyranny, explains in part why Tocqueville thinks democracy is more susceptible to despotism than other regimes, not less.

If humans are meant for more than mere existence, they must look beyond liberalism for answers.

Goldberg too cavalierly dismisses the search for meaning as a romantic notion. Tocqueville saw it as a natural human desire. As Walker Percy noted well, people need answers to the questions “Who am I?” and “What am I supposed to do?” Leaving it up to “choice” with no content is insufficient. Goldberg claims “through reason and argument we can identify good ideas and bad.” Perhaps. But can we identify the Good and the Bad? Liberalism on its own struggles to provide answers to Percy’s questions, or can provide no other answers than: an isolated individual desiring self-preservation and comfort. This is tantamount to saying we exist merely to exist. That is the reductionist view. If humans are meant for more than mere existence, they must look beyond liberalism for answers.

Goldberg argues that romantic art and popular culture are suffused with “the idea that contemporary life was out of balance and off-kilter, inauthentic, or oppressive, and that elites and the system itself were broken, corrupt, or inadequate to the task of making life right.” But this is also the view of Percy and Flannery O’Connor. No one would accuse either of being “romantic” in their vision. O’Connor’s stories portray the dark side of the self-contentment of the bourgeois life Goldberg celebrates, a self-contentment masking a horrible nihilism. Percy believed the novelist–and the artist in general–sees truths the scientist can’t see. Those truths may be more important than scientific truth, namely the truth of who we are and what we are supposed to do. Goldberg also has answers to those questions. Who are we? Beasts, mere animals. What are we supposed to do? Whatever we want, or put differently, nothing in particular. The artist who most captures Goldberg’s view is Ayn Rand: unsentimental, calculating, celebrating the sovereign self, contemptuous of romanticism.

Ultimately Goldberg’s limited defense of civil society, religion, and family is not so much that these are goods in themselves, but that they are useful for making us wealthy and content. Percy and O’Connor, along with Tocqueville, appreciated the danger of worshiping choice to the exclusion of goodness; the self to the exclusion of God; the “consumer” to the exclusion of the person; science to the exclusion of poetry. They saw through the self-satisfaction of the modern “subtraction story” and saw that ancient religious truths spoke more to the human experience than the solipsism of liberalism.

Bravo!…Bravo!

Jonah Goldberg has exposed himself in this book.

“And herein lies the central problem of the book. Almost the entire work is given over to a reductionist, materialist, autonomous individualist view of humanity and society. Only in the last pages of the book does Goldberg lament a decline in civil society, family, and religion. Yet this decline is a direct result of the book’s principal commitments.”

Thank you for your brilliant review.

Well darn. I just bought this book and now I don’t want to read it!!!

The world was lately made empirical,

Getting and spending, we increased our powers;

What little we saw in Nature now is ours;

We have rid ourselves of hearts, a Miracle!

—Jonah Goldberg

A well-argued review, and yes, I’d agree that liberalism contains all the disorders that Goldberg sees as threats to democracy. But it’s wrong to say that his reliance on Game of Thrones tells anything of value about his thesis, rather than about Goldberg himself. And I believe it’s also wrong to object to reductionist and materialist views simply because they fail to answer Walker Percy’s questions–or they omit “poetry.” They aren’t meant to..

Comments are closed.