There are many surprising things about getting older. As I sit on the cusp of my late thirties, staring at that blinking cultural landmark a few years down the road, a couple of these surprising things have happened to me. Fly fishing, for example, a casual and seasonal hobby for two decades, became in 2018 something closer to a total obsession. I can’t point to anything specific that caused this; it just suddenly occupied my thoughts and free time constantly, and I even find myself dreaming about it. Weekends—and many weekdays—are now structured around dry-fly mornings and bass-popper evenings, with my eastern Kansas waterways providing plenty of largemouth, crappie, bluegill, and other humble (but proud) species.

Perhaps the even more unpredictable thing is this: suddenly I became a huge fan of Jimmy Buffett. Well, perhaps not suddenly. It was more like Hemingway’s remark about bankruptcy: it happened slowly, then all at once. Like most people, I was tangentially aware of Buffett’s hits and his status as a jukebox touchstone, but I didn’t know much beyond the five or ten most famous songs. I knew that my parents had been big fans in the 1970s, but I wasn’t sure why. Oddly, I read Buffett’s midlife-crisis book, A Pirate Looks at Fifty, when I was 18, and it enthralled me with its tales of picking up and setting off for the islands. Perhaps all of this was Buffett happening to me slowly. Then one cold February day, sitting bored at a computer in a silent office, I turned on Buffett’s 1974 album A1A. And then all-at-once hit me like a ton of Duval Street bricks.

A1Ais one of five albums Buffett released during his so-called “Key West phase,” where he famously fled to escape the drudgeries of mainland life. The batch also includes A White Sport Coat and a Pink Crustacean (1973), Living and Dying in ¾ Time (1974), Havana Daydreamin’ (1976), and Changes in Latitudes, Changes in Attitudes (1977). (1978’s Son of a Son of a Sailor is sometimes added to this list.) These five albums represent the 1970s counterculture at its beachy best, and they offer a sharp contrast to the gritty, urban upheavals we often associate with that decade.

If not quite a beachside Wendell Berry, Buffett is indisputably an advocate of limits, humility, and acceptance of fate.

What’s so appealing about the Key West albums is Buffett’s overarching message. It’s a more relaxed and less nihilistic version of “tune in, turn on, drop out,” but it carries the same symbolic power: sure, you could dedicate your life to consumption, accumulation, and acquisition—or you could order an umbrella drink and watch the sunset. If not quite a beachside Wendell Berry, Buffett is indisputably an advocate of limits, humility, and acceptance of fate. It’s a message revealed throughout the Key West albums, which are some of American music’s finest. Two are great (White Sport Coat and Havana), two are outstanding (Living and Changes), and one, A1A, must be declared an American classic.

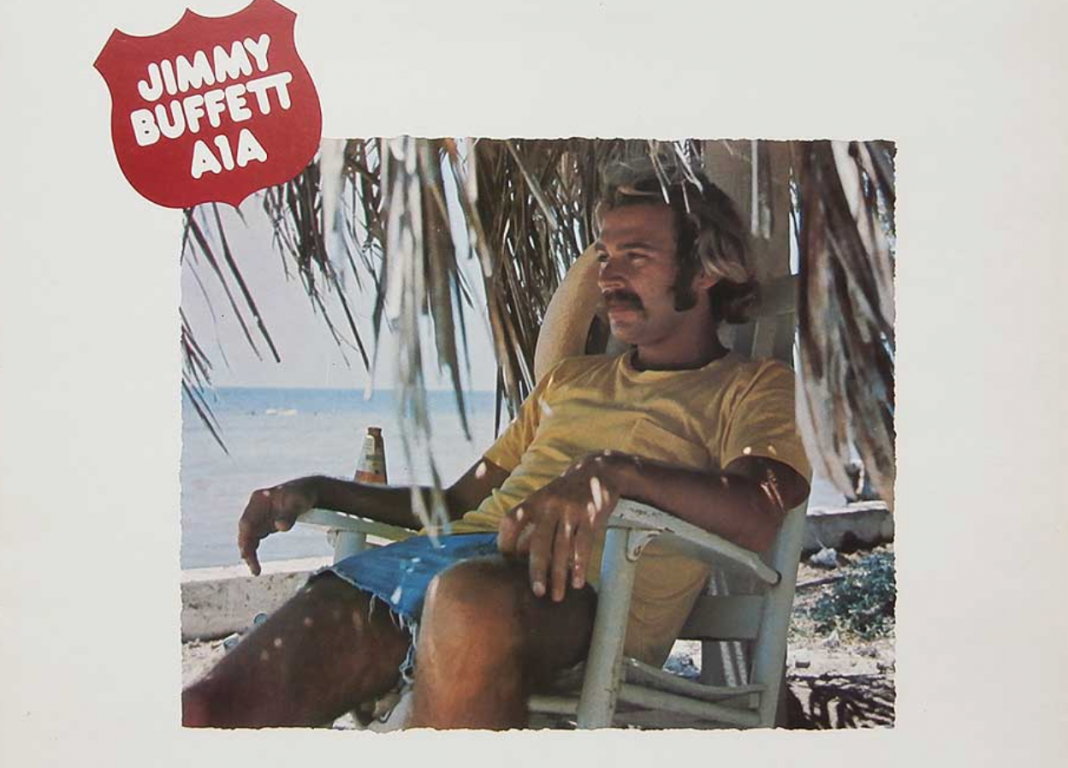

That album is a perfect distillation of Buffett’s philosophy, right down to the album cover depicting a peaceful Buffett, in denim cutoffs and t-shirt, sitting calmly under a palm tree, beer at hand, gazing out at the Gulf. The songs continue this theme: “Tin Cup Chalice” celebrates modesty and simplicity, in which we use a “tin cup for a chalice,” filled “up with good red wine.” “A Pirate Looks at Forty” tells the story of an “over forty victim of fate” who finds modern career options unsatisfying (his “occupational hazard” is that “his occupation’s just not around”) and tends bar instead. “Trying to Reason With Hurricane Season” is a testament to the wisdom of stepping away from the frantic life. “Stories We Could Tell” is an homage to the tender moments a couple shares. “Nautical Wheelers” toasts those who are “more than content to be livin’ and dyin’ in ¾ time.”

The men and women in Buffett’s songs are those who consciously choose a slower life, a more peaceful existence, and a simpler approach to all things.

This latter line could be the guiding ethos of Buffettian living, and we can compare it to another famous American B: Melville’s Bartleby, whose regular refrain—“I would prefer not to”—has been adopted by everyone from existential philosophers to the Occupy Movement as a rejoinder to a culture that screeches, in bright neon lights, MORE MORE MORE! The men and women in Buffett’s songs are those who consciously choose a slower life, a more peaceful existence, and a simpler approach to all things. In the same way the Sabbath offers a quiet resistance to our Empire of Acquisition, Buffett’s strategic withdrawal to the beach house in your mind offers a form of escape from the deskbound life. Even if you can’t stroll over to the beachside café, you can simply say: no thanks, I’ll just watch the birds out the window.

Even when Buffett sings about life on the road, his work is not the Zeppelin-esque stuff of parties and groupies. He just wants to go back to a quiet place with a breeze and a beach umbrella. In “Come Monday”—which, had it been written by Bruce Springsteen or Bob Dylan, would be considered one of the greatest American songs—Buffett enjoys nothing about Los Angeles and “just want[s] you back by my side.” His taste is always simple (“I got my Hush Puppies on/I guess I never was meant for glitter rock and roll”), and it’s those simple things that provide the most comfort, as in “The Wino and I Know”: “Cause I’m livin’ on things that excite me/Be they pastries or lobsters or love.” Even “Cheeseburger in Paradise,” which at first glance is a goofy novelty single designed for a marketing campaign, is actually a paean to gratitude and simplicity. After a harrowing sailboat journey and a few days of subsisting on canned food and peanut butter, Buffett pulled into port and enjoyed a simple cheeseburger that tasted, no doubt, like heaven.

Though Buffett’s songs often depict physical escapes to the islands, the real escape is metaphysical. In “Banana Republics,” Buffett writes that the American expats are “feelin’ so all alone/Tellin’ themselves the same lies/That they told themselves back home.” There is no withdrawing from modern life; running away to St. Bart’s is not the same as running away from yourself. But throughout the albums Buffett stresses the importance of mental departure, of being mindful of the rat race qua rat race, and doing your part to play a smaller role in it. More money? More stuff? More work? I would prefer not to.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how we might translate this kind of thinking into our daily, workaday lives. If you are reading Front Porch Republic, you probably already support limits, humility, simplicity, thrift, and some degree of strategic withdrawal from maniacal capitalism. But is this enough? We live in a culture of immediacy and constant connection, a world of pings and alerts and updates, with every voice competing to offer the most controversial “take” on the latest pseudo-news. We struggle with shortened attention spans and rewired brains. The glow of screens, each pixel representing someplace other than where you actually are, illuminates our civilization no less than our faces.

We need to live not just slower physical lives but also slower mental lives.

Perhaps Buffett offers a clue here, directing us to what we might call Slow Living. Settle for less. Switch from online news to your local print newspaper. Skip at least five purchases per week. Give away a quarter of your clothing and books. Rather than wishing you had more money, commit to spending less each day. But even more importantly, pay attention. Be aware of the impulses within yourself that drive you to distraction and frenzy, and then remove them from your daily life. We need to live not just slower physical lives but also slower mental lives. Unfashionable though it may be, we need a return of slow, contemplative living. We need a return of preferring not to, of operating in ¾ time.

It’s not so odd, in fact, that Buffett and fly fishing would hit me concurrently. Buffett has been fly fishing for decades, and in the 1970s he fished frequently with Tom McGuane, Jim Harrison, Richard Brautigan, and Guy de la Valdene. No doubt there is something in fly fishing that allows room for contemplation, for metaphysical escape, and for letting the water flow past you as you appreciate the simple variables of line, water, and fish. The beach and the trout stream are not so different: both are fine places for metaphysical escape and slowing down your internal clock. What could be more salutary in our age of anxiety?

Pick up a fly rod. Listen to Jimmy. Both will be good for you.

Thank you so much for this. As I have come to to know Jimmy more over the years I have come to respect him more. He really does have a … message. I guess it really surprised me that he’s about more than partying down via a cold margarita with salt on the rim. My first clue was “He Went to Paris”.

Thanks, a good read and good thoughts…but at late-30s you’re just a young’un, and your opening paragraph, with the “obsession” reference, belies a reluctance to fully embrace the rest of the ideas. Being obsessed by anything, including flyfishing, is not healthy, nor is it Buffet-esque. Let Slow Living also apply to it; enjoy and give thanks for the bounty while you may, but in it’s proper Place flyfishing is not even very important and should be able to be given up at the drop of a hat, if need arises.

A very nice essay. It makes me miss my home state of Florida, if not all of the newcomers who have been making it unlivable since ca. 1964.

[…] I visited Front Porch Republic for the first time in too long, and came across this article: Thinking and Writing in ¾ Time: A Few Thoughts on Jimmy Buffett, which captures more eloquently than I much of the reason I love Jimmy Buffett’s […]

Think I’ll go out and buy a fly rod.

[…] I visited Front Porch Republic for the first time in too long, and came across this article: Thinking and Writing in ¾ Time: A Few Thoughts on Jimmy Buffett, which captures more eloquently than I much of the reason I love Jimmy Buffett’s […]

Comments are closed.