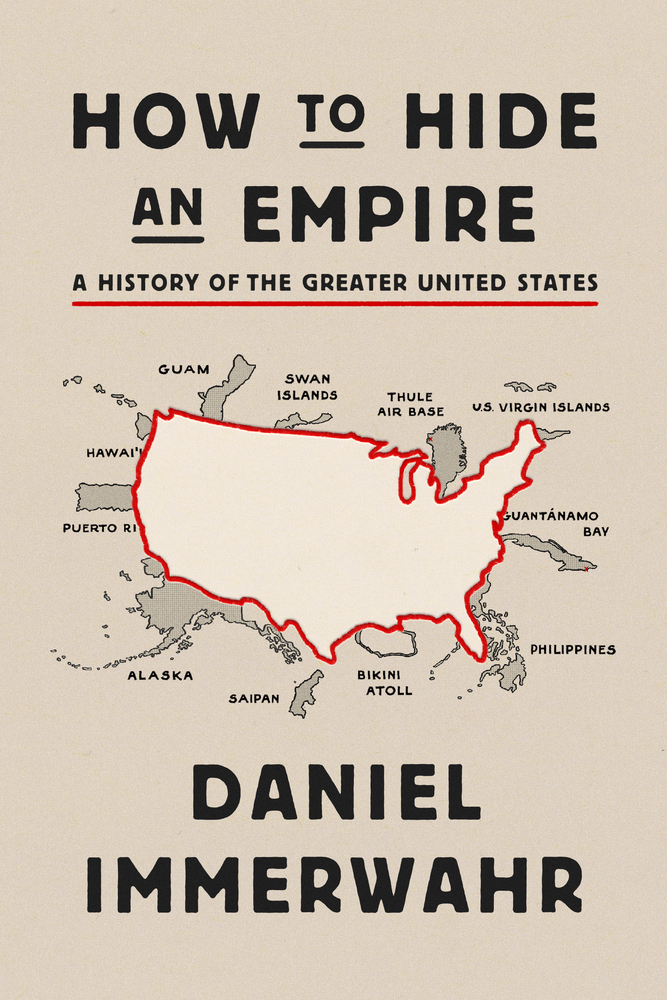

In How to Hide an Empire, Daniel Immerwahr lays bare the consequences of the American empire and how this history has been ignored by citizens of the United States. It’s an unflinching look at America’s expansionist foreign policy throughout our history.

Immerwahr, an associate professor of history at Northwestern University, tells the story of America’s territories and colonies from the perspective of the people who live there. “One of the truly distinctive features of the United States’ empire is how persistently ignored it has been,” he writes, and his goal is to give “a full portrait of the country—not as it appears in its fantasies, but as it actually is.”

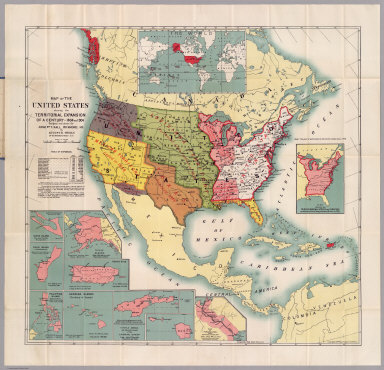

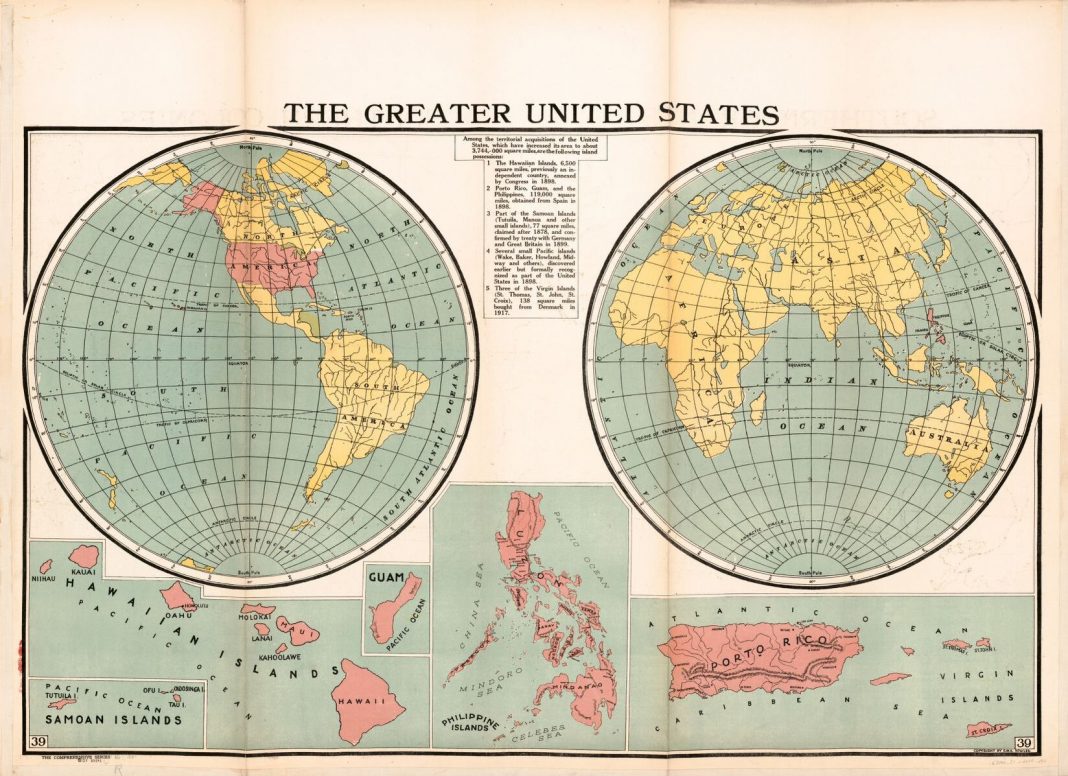

The first part of How to Hide an Empire covers the “Colonial Empire,” a history of how the United States expanded to the Pacific Ocean and beyond, the Spanish-American war and the conquest of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, up to the Japanese conquest of the Philippines at the beginning of World War II.

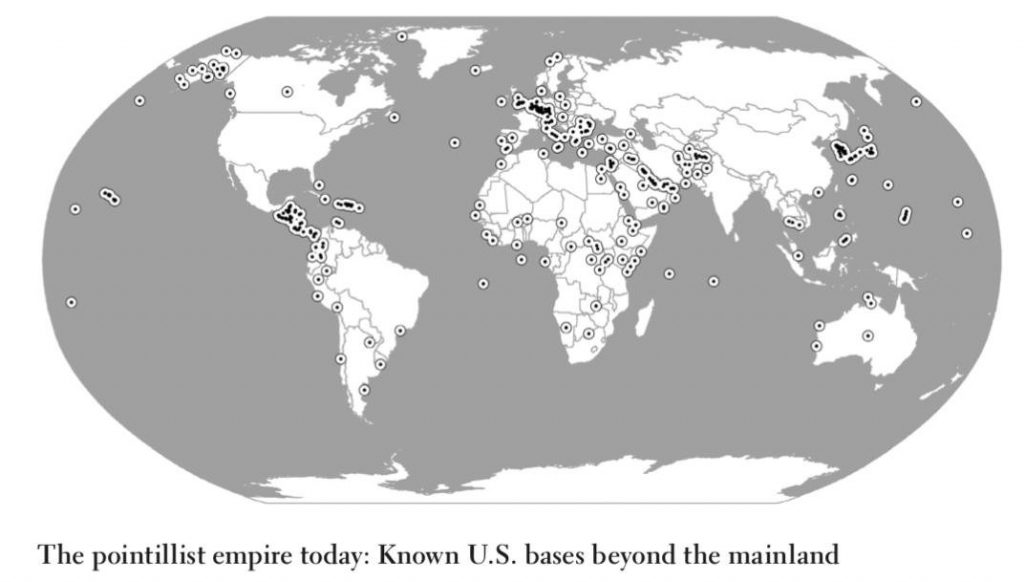

The second part covers the “Pointillist Empire,” which chronicles how the U.S. gave up its overseas possessions, the technological and economic changes that made colonialism less valuable, and the spread of military bases across the world to ensure dominance. The pointillist empire refers to the hundreds of American military bases worldwide; rather than holding large tracts of land to safeguard natural resources or economic connections, Immerwahr argues, modern technology makes projecting power easier by holding smaller pieces of land at strategic points.

The full portrait of empire Immerwahr wants to present is easy to ignore for most Americans. For one, the map of the U.S., past and present, rarely showed all territory under American control. The “logo map” that shows the contiguous 48 states (and sometimes Alaska and Hawaii) is the United States in the American imagination.

But a map of the Greater United States, which shows all American territory, is rarely used, even though large numbers of American citizens and nationals lived beyond the states. As late as 1940, 18.8 million people lived in the territories of Alaska, Hawai’i, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, the Panama Canal Zone, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Guam, and America Samoa, while 131.7 million people lived on the mainland. The number of people living in the territories was more than the entire African American population on the mainland.

Even the name “United States” is misleading: Since independence, the United States has been “an amalgam of states and territory,” Immerwahr notes, and the Constitution has just one sentence focused on governing non-state territory.

Self-government was not the default in far-flung American enclaves; instead, sweeping power over them was wielded by Congress and the U.S. Department of the Interior. The consequences mirrored the experience of colonies controlled by European powers: territorial disenfranchisement, wartime abuses, and unrestricted governmental experiments, from urban planning in the Philippines to eugenicist projects in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rico, for example, was a hub of sorts for medical testing. The birth control pill (and female sterilization) were pioneered there by Gregory Pincus, a Harvard-educated doctor.

The overseas territories “functioned as laboratories, spaces for bold experimentation where ideas could be tried with practically no resistance, oversight, or consequences,” Immerwahr writes. American education would be better if this ugly aspect of history were incorporated: Just as the British empire saw fit to deny basic rights and liberties to the American colonies, so did the American empire to its own colonies. The temptation to act as tyrants in far-off places is seductive to all sorts of governments.

The Constitutional rights and self-government on which most histories of America center themselves often did not extend beyond the borders of the mainland states, as Immerwahr explains. That correction of the record is what makes How to Hide an Empire valuable reading: many Americans are completely unaware of this aspect of their history.

An overarching theme throughout Immerwahr’s work is how mainland Americans had little knowledge or awareness of colonial abuses. They were rarely forced to learn of them except in extraordinary circumstances, such as when Puerto Rican nationalists tried to assassinate Harry S. Truman in 1950. Even then, however, the lessons learned on the mainland tended to be stereotypes about “Puerto Rican gangs, dope fiends, and switchblade artists,” Immerwahr writes.

Another point of emphasis was how often local desires were ignored in favor of what was convenient for the federal government. Rarely could territorial residents push back against federally appointed governors. That powerlessness manifested in repeated denials for the Philippines or Puerto Rico to gain statehood or independence, as well as three years of martial law in Hawai’i.

A driving force that shaped which territories would have a chance at statehood was the fear in government halls of admitting a non-white state. From a proposed Indian state with a Congressional delegate, to admitting Puerto Rico, the Philippines, or Hawai’i in an earlier “annexation,” the image of the United States as an “Anglo-Saxon” nation prevented territories from gaining self-government and representation, Immerwahr argues.

The American empire was not abolished, with a clear and certain end. Instead, its evolution was shaped by economic and military circumstances, Immerwahr argues. As technological progress created synthetic substitutes for goods such as rubber, silk, and copper, the benefits of holding colonies fell as its costs (driven by anti-colonial revolts after World War II) rose. The American economy, Immerwahr writes, “replaced colonies with chemistry.”

Meanwhile, the military embraced pointillism. Bases in strategic locations ensured American dominance without the costs of holding large areas of land. This “pointillist empire,” in concrete terms, means that more than 800 US military installations stretch across the Earth, from Greenland to Cuba to Djibouti to Brazil.

Bases also gave the American government territory under its control but beyond accountability. “They were places where, in the words of Doctor No, the United States would have to ‘account to no one,’’ Immerwahr writes. Actions by the military or by the government, unrestricted by Constitutional limits or democratic accountability, often brought out the worst from those on the government payroll. Immerwahr highlights the “water cure” widely used in the 14-year Philippine-American War and the 1937 Ponce Massacre in Puerto Rico, among others, to show an ugly American tradition that continued into the 21st century with the War on Terror’s indefinite detention, torture, and extraordinary rendition.

One thread that Immerwahr doesn’t weave into his narrative is the connection between American imperialism and progressivism. Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson appear (rightly so) as expansionist villains. The Malthusian Gregory Pincus in Puerto Rico had a connection to Planned Parenthood, being generously funded by eugenicist Margaret Sanger. The architect Daniel Burnham, a proto-Robert Moses figure, was given free reign to design Manila and Baguio in the Philippines as he saw fit. American progressivism has had an unfortunate affinity for centralizing great amounts of power without creating any defenses for the people subject to it. That “rule by experts” ran roughshod over basic human rights and the limitations on government power; the history of American empire cannot be decoupled from the history of American progressivism.

How to Hide an Empire is a sobering read for those who hope enlightened government officials far away from the people they govern can improve the lives of the populace. Throughout Immerwahr’s work, the question echoes: How can one square this history of America as a domineering force abroad, quick to embrace brutal violence, with the mythology of the United States as a symbol of liberation and freedom?

America has been a beacon of light, but it’s also been a fearsome master. The shame of American history should not drive the public to nihilism, but it should urge them to weigh the dangers of immense government power and seek to make it more accountable to those over whom it holds sway.

Immerwahr is truly a fabulous name for an historian!

I’ve never liked this sort of thing because I think the word Empire evokes something like the British Empire, India, etc., and the US whatever-it-is just fundamentally isn’t like that, partly because the late 20th century is fundamentally different from the 19th century. And those large number of dots on that map span such a massive range of types of “bases” that it’s quite misleading to show as is.

Use of “empire” to describe America has always been a political/philosophical thing, so it is actually pretty jarring to read this sort of analysis after the last few years of madness. The complete and total political and media meltdown when it was proposed that the US should leave Syria (a conflict whose US involvement has never been and never will be approved of by the public or the legislature) would surely confuse any good leftist who might have fell into a coma a few years ago. Even Bernie Sanders who famously honeymooned in the USSR for cripe’s sake was against withdrawal!

Strange times we live in, when endless foreign wars and CIA plots to remove a US president are ++good…

“One of the truly distinctive features of the United States’ empire is how persistently ignored it has been,” needs a caveat: Ignored by whom? Not academic historians, certainly. In fact, “empire” as an interpretive lens has been ubiquitous in its application to the US, Britain, France, Soviet Russia, Russia, and so on, for the last 30 years.

So who isn’t thinking about the U.S as an empire? High school history textbooks? I’d be interested to know more about Immerwahr’s answer to that.

“ How to Hide an Empire is a sobering read for those who hope enlightened government officials far away from the people they govern can improve the lives of the populace. Throughout Immerwahr’s work, the question echoes: How can one square this history of America as a domineering force abroad, quick to embrace brutal violence, with the mythology of the United States as a symbol of liberation and freedom?”

It strikes me that those who view “enlightened officials far away from the people they govern” through rose-colored glasses are fundamentally anti-American. The essence of the American idea is that no man is fit for unaccountable rule over his fellow men. It is only insofar that Americans have faithfully embodied this idea throughout our history, that we are a “symbol of liberation and freedom.” But who among the Founders would have been so naive to think that every future American governing official would stay true to this idea?

The mere holding of American citizenship — or of office in American government — does not ensure adherence, or even attempted adherence, to the American ideals of governance. Anyone who has ever thought as much is a fool. Anyone who was ever under the impression that American history is a story of our governing officials acting in blind obedience to our constitution, and the natural rights philosophy which birthed it, is a fool. Our institutions are painstakingly designed to resist the contrivances of the corrupt men who will inevitably comprise them.

The authors of our constitution would have taken it to be an a priori truth that future American governing officials would strive to escape the checks placed upon their power by our political edifice. So to point out that our history is now littered with officials who have, when possible, violated the natural rights of those they governed, is simply to state the obvious.

The interesting question is not whether or to what extent the American government has abused its territorial holdings — rather, it is how the American people became so naive as to think their government would, in infinite benevolence, never violate the founding spirit of their nation.

The content of this book review may seem “obvious” but I bet the book itself has a lot of details that will seem new to you (and me). I personally was “naive” about the US granting independence to the Philippines in 1948 until I visited the national museum in Manila 40 years later and saw a detailed display of how they actually got independence in 1898, but then “we” took it away from them. Wilson, among other scholars at US elite colleges, taught courses in “The Governance of Tropical Dependencies”.

As for violating the founding spirit, there was in fact a fierce debate in the US senate after the Spanish American War about whether we would become a colonizer or remain true to our destiny as an exemplar of liberation. You can guess who won.

I appreciate Hennen’s paragraph about Progressivism, which provides good perspective on neoliberalism. Margaret Sanger published a newsletter which is archived online by several universities. She proposed a “child” license analogous to a marriage license, which would restrict reproductive freedom even more than China’s one-child policy (which didn’t dictate when you could have your one child). Her UK counterpart Marie Stopes used eugenicist terminology when urging more births among A1 people and fewer among C3 — it seems that Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World didn’t introduce these ranks to readers but rather adopted a classification that was already in vogue.

Comments are closed.