Nostalgia’s got a bad rap, especially lately, with Trump’s banal slogan “Make America Great Again.” “When exactly was America great?” we might rightly ask. “When black people and women couldn’t vote?” In some forms, nostalgia is certainly noxious, a means of covering up the sins of the past under an idealistic patina of virtue, real or imagined. But that’s not always what nostalgia is—and, in addition to being nearly inescapable, it has indispensable benefits, provided it’s kept within reasonable limits.

First we must acknowledge that we mean at least two different things when we use the word nostalgia. On the one hand, it refers to a sort of semi-pleasant homesickness; the word was in fact coined by the Swiss physician Johannes Hofer in 1688, trying to describe the experience of soldiers who’d been deployed for too long; it was even used as a cause of death until the early 20th century. On the other hand, it refers to what the sociologist Fred Davis calls “antiquarian feeling,” which takes place when a person identifies emotionally with a time period they never personally experienced. It’s antiquarian feeling that Woody Allen skewers in Midnight in Paris and Edwin Arlington Robinson in “Miniver Cheevy.” Both nostalgia proper and this antiquarian feeling are fundamentally acts of the imagination, but nostalgia, at least, is mixed with memory, whereas the world I long for in antiquarian feeling is one I have created, if not out of whole cloth, then out of patches of romances and novels, like poor Don Quixote.

A slogan like “Make America Great Again” would thus be nostalgia if it were an appeal to return to its hearers’ childhood. I suspect, however, that many people to whom it appeals were not alive in the supposed glory days of the 1950s. More to the point, by not evoking an actual time period, it allows each Trump supporter to fill in the blank with whatever long-lost age of virtue most appeals to them. It’s a sort of amorphous and subjectivist antiquarianism. And the fact that the campaign’s 2020 slogan is “Keep America Great” suggests that it was never about our relationship to the past, real or imagined, but to Trump himself.

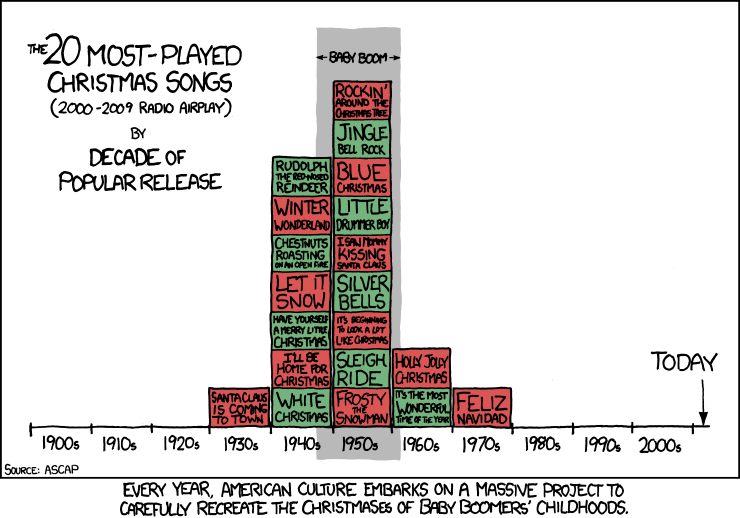

Antiquarian feeling thus stands on even shakier ground than nostalgia proper, though I will argue that both of them, properly deployed and understood, have a place in our ethics and even our politics. It can be hard to see that place, however, because a kind of commercialized nostalgia holds terrible sway in our mass culture, and has for a long time. I don’t think the Baby Boomers invented nostalgia as a consumer product—there are episodes of Bing Crosby’s radio show from the 1930s that feature entirely songs from its audience’s childhood in the dawn of mass culture—but the Boomers certainly took it to a new level. Think about the hit ‘50s throwbacks of the late ‘70s, from Grease to Happy Days. Even the Woodstock Festival, supposedly a collection of artists on the vanguard, opened with a performance by Sha Na Na, a corny ‘50s nostalgia act. The Baby Boomers, in some ways, are defined by their interest in the era of their own childhoods, as this comic from xkcd nicely demonstrates. Their children were raised in a culture that unironically used phrases like “classic rock” and “the golden age of television.” As a child, I’d memorized the hundred songs on the playlist of Fox 97, Atlanta’s “oldies” station, but I likely couldn’t have named four songs on Billboard’s Hot 100. I can’t imagine I’m the only one. Thus we began life with a sort of antiquarian feeling for a 1960s and ‘70s that we never experienced. The hit 1990s show That ‘70s Show, to the degree it was pitched at teenage millennials, was not the equivalent of Happy Days; it was created by Baby Boomers and celebrated their own teen and young-adult years.

It’d be easy to point to all this nostalgia as evidence of what a character on the sitcom Community called the Boomers’ “well-documented historical vanity”—exhibit A for the Me Generation’s Culture of Narcissism. But that accusation ignores the near universality of our longing to return to childhood. As Mary Warnock puts it, “The past is a paradise from which we are necessarily excluded, and this is true even though, when it was present, it was less than paradisaical” (77). We all want to return to a more innocent era, and we usually think of that era as our childhood—not because our world was actually simpler then (though perhaps it was), but because our relationship to it was. The difference between the Boomers and every generation before them is not that they were nostalgic but that, for the first time in human history, their primary relationship with the world came through the consumer artifacts of mass culture. The advertisers and culture-mongers, understanding better than most people our longing for our imagined simplicity, knew they could make a mint off it. And, boy, did they.

However much we might criticize the Baby Boomers for their nostalgia, Generation X and the Millennials have taken things even further. And here, too, our nostalgia is fed to us by mass culture, which is even more pervasive and all-consuming than it was during the 1970s. Think of a show like Stranger Things, which reproduces the 1980s via a series of pastiches of the popular culture of the era: Stephen King, Steven Spielberg, John Carpenter. And it peppers these pastiches with in-universe references to the cultural artifacts of the era, such that part of the pleasure of watching the show comes from sharing the characters’ love of The Clash and Back to the Future. I was born in 1982, and most of my memories of the 1980s are vague and impressionistic; Stranger Things triggers these memories so strongly that it makes me wonder if they weren’t all the products of ‘80s-set pop culture to begin with. I’m more at home in throwbacks to the 1990s like Captain Marvel and Fresh Off the Boat, both of which evoke the decade’s atmosphere with cultural fads: gangsta rap, starter jackets, “Just a Girl.” Watching them, I think I understand what it’s like to be a Baby Boomer: my every emotional button is pushed by their mere existence, and I turn off the television momentarily satiated and a little sad, albeit pleasantly so. This sort of corporation-backed nostalgia is harmless and useless at the very best. But we should be skeptical any time mass culture plays around with the deepest parts of ourselves, because it’s generally doing so not to tell us the truth about ourselves and our world but to sell us something—or, in the case of network television, to sell our attention to advertisers.

All the same, almost all of us occasionally remember our childhoods as a kind of lost Garden of Eden. And there’s a real and beneficial purpose to that longing. It tends to arise during painful periods in the present day; we remember the past as a time when that pain didn’t exist, or at least didn’t dominate: “I was happy back then.” Often this is a whitewashed view of the past. I remember a period of my college years in which I was so miserable that I could hardly sleep through the night. I’d stay up all night writing depressing music. It only took a few years for me to start romanticizing that period, looking back on it as if I were some tortured genius in a movie, beautifully and nobly suffering for the sake of my art. Nostalgia often operates this way: I think of the past not as a real entity in itself but as a negative image of my present boredom and unhappiness. And because the person I am now is to some extent unrecognizable to me, I dredge up a memory of who I was, whom I understand myself to be. As Edward Casey says of the form of memory called reminiscence,

this reliving amounts to insinuating ourselves back into the past—re-experiencing a certain cul-de-sac, a pocket of time into which only one’s self, accompanied or not by immediate companions, can possibly fit. Indeed, it is the very snugness of this fit between the present self and its past experiences that we at once need (as a pre-condition) and seek (so as to strengthen the bond between the two). (109)

Here is a beneficial use of nostalgia proper: By comparing the self I currently inhabit like a stranger with the self I once was, I create a space wherein I can understand who I am and who I have been. I am given things to be proud of and, provided my nostalgic sense is not overpowering, things to be ashamed of and to repent of. This can happen, however, only when I reflect on my nostalgic feelings rather than taking them at face value. Nostalgia is a helpful servant but a vicious master, and if I accept it uncritically I will be terribly unhappy, like the aging actress in a memorable Twilight Zone episode who spends so much time miserably watching her old performances that she eventually disappears into the film stock.

Antiquarian feeling is even more dangerous, because I don’t have the check of personal experience to keep me from falsifying the past. I can read history books that demonstrate that my preferred era is not what I imagine it to be, but facts are a poor corrective to the imagination. In this sense, antiquarian feeling is a form of idealism, and shares the risks of idealism. When I have a vision of an ideal spouse, for example, I can let my actual wife’s failure to live up to that ideal blind me to what makes her wonderful. Likewise, my idealized image of a glorious past can make me miserable in the present, like Robinson’s Miniver Cheevy, who wants to live in the storybook Middle Ages and spends his days in an alcoholic haze, blind to his own failures:

Miniver scorned the gold he sought,

But sore annoyed was he without it;

Miniver thought, and thought, and thought,

And thought about it.

But idealism can be useful, again when we see it as a tool rather than a way of life. It gives us a way to critique the world we live in by giving us the virtues we wish it would have. In fixating on the supposed chivalry of the medieval knight, Miniver Cheevy ought to become more chivalrous himself—even or especially if real knights were not particularly chivalrous. Again, reflection is the key: I must recognize my antiquarian feeling for what it is rather than accepting it as the truth about my own era or any other. As a spur to making my world and myself better, antiquarian feeling is a valuable emotion, but without reflection about what values I admire in my imaginary 1950s (or whenever), I will be drawn into an invincible hypocrisy, unable to recognize the truth about myself or the world I live in. Antiquarian feeling, at its best, is a kind of embodied virtue, but we must always recognize that its virtues are not the only virtues.

Nostalgia and antiquarian feeling are fundamentally modes of the imagination. Dismissing them outright makes about as much sense as dismissing the imagination itself outright—but at the same time, trusting them uncritically is likely to lead us down some dark and dangerous alleyways. At their best, nostalgia and antiquarian feeling can give us real hope, a vision of a world beyond the here and now, a world of virtue that may not presently exist. In his autobiography, Surprised by Joy, C.S. Lewis talks about having been drawn to Christianity by a feeling of “joy,” a sort of unsatisfied longing that let him know there must be something otherworldly to satisfy it. Nostalgia, properly understood, is just this sort of joy—a sweet sadness that reminds us there’s something more to life than the brute facts of the here and now.

I read something a few years back that made the point that although we generally think of nostalgia as being related to time, it almost always has a place element to it as well: the time period that you remember with fondness or chronological “homesickness” is linked to the place where you were at that time.

I happened to read a very good essay just yesterday that brought this all back to mind, “Putting Two and Two Together” by Chris Arthur. It appears in his book Hummingbirds Between the Pages, and it’s also on JSTOR if you’re a subscriber.

Comments are closed.