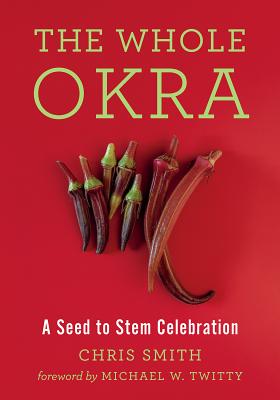

Buncombe County, NC. Chris Smith considered titling his 2019 book “In Defense of Okra.” Instead, he opted for The Whole Okra: A Seed to Stem Celebration (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2019). His book’s selection as a 2020 James Beard Award Winner indicates that his choice for the title was one of several excellent choices that Smith made. After growing okra last year in the Mars Hill University Heritage Garden and reading Smith’s book, I am ready to join the okra-bration; frankly, I am now embarrassed to have been among those who dismissed a plant with so many merits. In the space of a single growing season, I went from doubter to defender. I offer here three characteristics that contributed to my conversion.

I. Appearance

Okra plants are striking. A sturdy stem stretches skyward and supports broad leaves. While the plant itself is large, even imposing (some varieties grow twelve or more feet tall!), the flowers are delicate and ephemeral. Elegant blooms appear for a single day before being replaced.

Such contrast between frame and features gives okra an interesting appearance. Okra has the dimensions of a corn plant but blooms as eye-catching as a zucchini blossom. A sports analogy is out of place here, but I like to think of okra as the beautiful linebackers of the garden. And I daresay that the visuals they produce would enable them to hold their own if planted outside the garden among the landscaping.

II. Vigor

The COVID-19 pandemic has prompted many people to turn more of their attention toward their homes and yards. I have watched with delight as many new gardens have gone in this spring. I doubt okra tops many people’s list of garden must-haves, which is a shame since it is such a determined grower. Gardens are only guaranteed to produce one thing year in and year out: humility. Seeing frost erase our best laid plans overnight and watching as flood, drought, and pestilence drag down our plants is always deflating. Okra offers a buoying presence. Chris Smith writes,

Consider my average summer garden: There’s blight on my tomatoes, Mexican bean beetles are hammering my pole beans . . . , squash bugs have overrun the melons . . . , and striped cucumber beetles won’t even let the cucumbers get past Go. Vine borers have toppled my fall pumpkins and are having a good go at my ‘resistant’ butternuts. The heat has forced every annual green to bolt, downy mildew has browned my basil, and cabbageworms are greedily working their way through collards, kale, and any other brassica crop I was foolish enough to plant. But the okra keeps on growing.” (20)

Almost everyone thinks first of tomatoes, and that’s reasonable: in terms of taste, homegrown tomatoes are several degrees of magnitude better than their supermarket kin. But tomatoes can be fickle and delicate, especially the tastier heirloom varieties. Why not plant some okra, too? One of the perennial complaints about okra is that it is “just too productive.” That particular characteristic means that it might have the power to redeem an otherwise frustrating or lackluster season in the garden.

III. Versatility

Chris Smith takes his subtitle—A Seed to Stem Celebration—very seriously. His book includes nutritional information about okra sprouts and okra greens, dozens of recipes for the pods, as well as instructions for milling one’s own okra-seed flour. He explains that one can also press the seeds for oil, eat the flowers in several different ways, and that it’s possible to create paper from the fibers that make up the okra stem.

I only dabbled in okra last year. I ate the pods in several different ways—raw, pickled, and grilled—and made several batches of okra-seed-flour pancakes.

The seeds I saved from last year’s crop germinated early last month. This year I have a patch at home in addition to what we are growing at the MHU Heritage Garden. I have a plan for the okra at my house that embraces its versatility and vigor:

- I overplanted. As things got crowded, I thinned the stand and steamed some okra greens. They were good, but not good enough to displace beet greens as my top choice.

- As the pods arrive, I’ll pick and eat them (#sobold!).

- If things go well, the okra will overwhelm me. When I need a break, the pods that grow too tough for eating will make seed. I can shell that seed at my leisure. I’ll save some and mill some.

- When frost looms at season’s end, I’ll pick the flowers that wouldn’t have time to mature into pods and experiment with okra-flower vinegar.

Of course forming and publishing these plans has surely jinxed my okra . . .

Let us face the hard truth, okra is a cultural identity test. Are you among the elect or an outsider? That the author of the book, Chris Smith, a native of Britain, managed to develop an enthusiasm is remarkable. Because, and for a reason not among those mentioned by Ethan in his article/review, okra, and let us use the technical term for it, has a snot exuding quality that is a barrier to many.

We grow a couple of varieties in rotation on our farm. Fat stubby Hill Country Reds, and the classic Clemsons. This year we are trialing a Louisiana native, Dub Jenkins, that is doing beautifully. But, then again, the plants are damn near indestructible. I typically fry them, as I did this weekend, dipped in buttermilk and then rolled in cornmeal. Served alongside catfish subjected to the same loving care, with a platter of just sliced tomatoes, and a cold beer (or two or three) is a mighty fine way to wrap up a day of work on a Saturday evening.

During the summer months we will pickle them and serve them on the table for those discerning guests. But, honestly, you would be hard pressed to beat the commercial preparation readily available by the fine folks at Talk O’ Texas.

But the one thing you must never do with this vegetable is to put it in gumbo. For reasons beyond my ken, and I say this as a member of a family whose Louisiana roots date to the 1700’s, there is a crazy misconception that this is what you must do. No! That is nasty habit fostered by those urbanites of that Crescent City, which is found nestled in the mud along the lower reaches of the Mississsippi. Then again, now that I think about it, what do you expect from a people who can’t make a roux, stopping the process at a milky brown instead of a dark chocolate. I mean, some people.

It is, however, acceptable to add it to beef stew. But if you throw it over the fence to your garden pigs, well, they just turn up their noses at it. And let me tell you, the list of what hogs won’t eat is a mighty short one.

This is correct. I have a theoretical appreciation for okra, but the reality of the texture is too much.

I totally agree with you that the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted many people to pay more attention to their homes and backyards. I, an office clerk, suddenly started digging in my garden and get great pleasure from it.

Comments are closed.