Below is the introductory essay to the new issue of Local Culture, which is devoted to the practices of civil dissent. If you subscribe by March 1, you’ll receive this issue in your mailbox. You can whet your appetite by perusing the complete table of contents. Also, we’ve made PDF copies of the first two issues available for download here.

In the dark of the moon, in flying snow, in the dead of winter,

war spreading, families dying, the world in danger,

I walk the rocky hillside, sowing clover.

– Wendell Berry, “February 2, 1968”

Think of a man’s swinging dumb-bells for his health, when those springs [of life] are bubbling up in far-off pastures unsought by him!

– Thoreau, “Walking”

Do thou, too, remain warm among ice. Do thou, too, live in this world without being of it.

– Ishmael, in Moby-Dick

Authorities no less redoubtable than Jesus of Nazareth and Melville of Lansingburgh recommended being in but not of the world. Dispute their meaning how you will, you will be obliged sooner or later to admit that the being “in” part isn’t optional. Disaffection with the world as you find it doesn’t change the fact that you’re not going anywhere else. You might pound the pulpit about how “the world is not our home,” and perhaps in some ultimate sense it isn’t, but that doesn’t change the fact that at the moment it is our home. It is until it isn’t.

In like manner the fantasist suckled on a creed outsized might assure himself that in short order he’s sailing his Narrenschiff to Mars. But odds are it won’t be long before he realizes that his 80-year supply of Tang and dehydrated chicken dinners is staying right here with him. His high and noble hopes of savoring these delectables alone in a swirl of red Martian dust have been dashed by a stern preceptor called Reality, which tends to be as unimpressed with us as with our plans.

And let us not forget the Oval-Office hopefuls: they can make whatever mendacious promises about space travel that suit their ideas of public service. Still no one is leaving—not tomorrow, not next year, not ever. In all the heavens there floats one hospitable sphere suited to our flourishing, and we’re on it, and we have but one option: to reconcile ourselves to the limits of its assigned order. The alternative for fundamentalist, fantasist, and politician alike is to invite into this resplendent orb the penalties that reality invariably visits upon those who spurn both order and limits. Not escape from the world but pilgrimage through it: that is the blueprint.

And yet who in this world would willingly be of it? I mean besides almost everyone. Think only of the televisions that we’re apparently wholly reconciled to—televisions in the lobbies of every office and hostelry, in the once-hospitable bars and pubs of a perishing republic, in the diners on Main and the restaurants downtown, on the gas pumps of filling stations, in those former bowers of bliss called bedrooms, in (for the love of God!) back pockets—erstwhile works of sartorial art now desecrated by the disfiguring bulge of a petty rectangular tyrant.

To be in a world of screens and unceasing disquietude is one thing. But to be of it? Seriously?

Or think of all the architectural abortions that someone else has obliged you and me to behold day in and day out. Think of the agonies and absurdities of civic design. Think of the suburban catastrophes mushrooming above the tall-grass prairies as if these peaceful prairies were Bikini Atoll. Think of the bypasses choked and made frustrate by the automobile, that “mechanical Jacobin,” as Russell Kirk called it—“a revolutionary the more powerful for being insensate.” (“From courting customs to public architecture,” he said, “the automobile tears the old order apart.”) Think of the intersections of oil-stained macadam above which loom the omnibenevolent cameras that guard thy going out and thy coming in. Or, if nonconsensual surveillance photography doesn’t trouble you, think of the roadways with their ghastly high-tension string art right and left, before, behind, and above. “The modern dogma,” said Aldo Leopold, “is comfort at any cost,” even if the cost is health or beauty or both.

And what shall I more say? For the time would fail me to tell of the poisonous additives that make what little water remains in the aquifers drinkable, or of the topsoil that industrial farming must export to the oceans in order to offset the costs of its inputs. Long it were to tell of education sinking into consciousness-raising and grievance-tracking until it settles comfortably into the bliss of mere idiocy; of venerable liturgies Jekyll-and-Hyding into pole-barn therapy sessions in which, not surprisingly, electric guitars do little to mitigate the ennui of the regnant prosperity creed, hollow like the kick drums that stir its prophets into sabbath frenzies; of a highly lucrative weight-loss and exercise “industry” betokening complete capitulation to the doctrine of labor-saving and the scourge of inertia that follows hard upon it; of fast “food” and “microwave cooking”; of corporate welfare and corporate monopolies; of a citizenry breaking under heavy taxation and yet happy to pay additional taxes to Apple and Microsoft and Amazon and Google, not to mention the Stupid Tax it pays at slot machines and blackjack tables and state lotteries; of ordinary neighborly disagreements handed over to mediators or falling into litigation; of medicine lapsing into ex post facto button-pushing and state-sponsored coercion; of politics transmogrifying into tribalism, of civil discourse into civil war (don’t count it out); of self-reliance giving way to abject dependence on distant labor, distant food sources, foreign manufacture, and the fragility that bedevils attenuated supply lines.

A man might mention government of the elite, by the elite, and for the elite, and devil fetch the hindmost; he might mention fiscal “responsibility” on the part of elected officials that culminates in a national debt in excess of $30 trillion. At a certain point of absurdity he might as well add to the list the forward pass, triple-masking on solitary mountain hikes, and the AP style manual with its impious disparaging of the Oxford comma. In short order our man is standing on his front porch, shaking the newspaper at kids these days.

And why not? Is there a more constructive use for what the fourth estate produces?

Thoreau, exemplar of civil disobedience, if not prophet of civic dissent, famously said that “the greater part of what my neighbors call good I believe in my soul to be bad, and if I repent of anything, it is very likely to be my good behavior.”

It is true that you can’t pay your taxes with the eggs that your Ameraucanas and Isa Browns lay, lovely and tasty though those eggs be. I’m told you can scarcely bank without a personal computer or get from Monday’s time clock to Friday’s happy hour without having made several digital transactions that you might be tempted to doubt the existence of.

And what large-scale concern or public utility has not installed an automated customer disservice system designed specifically to make sure you can’t get your problem addressed, especially not by a son or daughter of the earth, there being no real people to talk to in these labyrinths of loneliness, where pressing “star” for “more options” never quite takes you far enough? “To learn how to open a vein and slip into a warm bath, please hold.” As for Kirk’s mechanical Jacobin (Edward Abbey called it a “bloody tyrant,” and Wendell Berry has numbered it among the “unprecedented monuments of destructiveness and waste”): the vast majority of Americans alive today were born into a “built environment” that was conceived and fashioned with little more than the automobile in mind, and so any sort of living without it is very difficult, public transportation and passenger rail being the punchlines that they are. Even those who do manage to live without a car nevertheless depend for most necessities upon long-distance transport of some sort. Drinkers of coffee and orange juice in my township, myself included, do not get their breakfasts by the grace of home production or mule carts.

Which is to say that many who look around and marvel at the all-encompassing ugliness and artificiality that were already waiting for them when they arrived on the scene, many who are constrained by social arrangements and systems and rules they never asked for or voted for and now recoil at—many of these people, many of us, are nevertheless deep inside the very bowels and intricacies of these systems, like lab rats in a maze that the cheese has been taken out of, no doubt to the mirth of those few disinterested observers who get to wear lab coats. Our willingness to go along is only partly relevant, for from the start our freedom to resist was never in any meaningful way granted.

Edward Abbey, aforementioned, said that when the rivers of your country are no longer fit to drink from, it’s time to get yourself a new country. But he didn’t mean you should take the Hemingway out or expatriate yourself to some other City of Lights and its nights of sodden slumber. He meant something like “get to work cleaning up the rivers and see that you don’t poison them again.” Abbey was a dissenter of the first water, and not always a civil dissenter, but he knew a problem or a monument to ugliness when he saw one, and he made no bones about opposing it. For example, he did not regard the earth a proper place for billboards, and a river on his account was a damn sight too close to human habitation for a dam site. And although like the rest of us he was guilty of plenty that censure could single out, in accordance with the old Leonard Cohen line he spent a long time watching from his lonely wooden tower, and from that dizzying height, as like Ishmael he revolved in his mind the problem of the universe, this fire-spotter found the stillness and the quiet and the leisure, far from the madding crowds and the hum of the dynamos, to wonder whether the fake arrangements of civilization—or what a pal of his called “syphilization”—could long endure the folly and abuses of its “beneficiaries,” much less its architects. And Abbey was not shy about recommending dynamite where picketing and protest didn’t cut the mustard.

But those less inclined toward Abbey’s brash example—theatrically throwing beer cans out his pickup truck window, for example, because, as he presciently discerned, future Americans would need gainful employment as trash collectors—will prefer more civil means of dissent. They can see that their children are learning next to nothing in the public schools and aught but lies at college, but they still want educated children. They can see that their families are eating poorly and without knowledge, conscience, or consciousness, and yet they know their families must eat—and fain would see them eat well. They see what merciless tyrants their phones and televisions and computers can be, and yet they would not be wholly beyond the thrum of American life. They are suspicious of experts in medicine and government and yet do not favor a return to blood-letting and tea taxes. They see the lapse of life-sustaining vocations into soul-crushing jobs. They have witnessed the ravages of automation, and they know or at least intuit that, as meaningful and honest livelihoods vanish, they take with them lives of honesty and meaning. “Alarm will sound” says the sign on the door that the disenfranchised exit through, and they can read it, but who for all those earbuds keeping reality at bay can hear the alarm?

They see this and much else and think enough is enough.

So although war spreads and families die and danger grows, in the dead of winter a man sows clover in the dark, in spite of death and darkness. And although elsewhere the narcissistic gurus peddle their scams for six-pack abs in the mirrored halls of selfhood and self-enclosure, the ghost of Walden turns his back on these dumbbells and their electric lights and HVAC systems to saunter under the sun and sky and to stroll through this earth’s still-fragrant breezes and across its leas and meadows where spring the fountains of life.

Let these two dissenters stand not as examples of opting out—not that, so much—but as examples of opting in. Sow the clover in the dark; in the light set out for the running water. Be in, not of. It is true that Ishmael went to sea because it was November in his soul, but he went befriending and befriended by a heathen, prepared to laugh at all the looming danger. A certain monomaniacal captain, by contrast, closed off from all the goodness and conviviality that men are still capable of, went otherwise. And the round ocean claimed him. Why go into this life, this one life,

like the quarry-slave at night,

Scourged to his dungeon,

while there is still backyard soil to drop seed potatoes into, neighbors to swap labor and tools with, frivolous gadgets to say No to, farmers’ markets and local small-scale shops to set your currency loose in, and a vapid news cycle heroically to ignore? The privileges of free association still obtain; the opportunities for self-reliance and local self-sufficiency still present themselves to anyone prepared to join hands with friend and cousin and take his tuition in the joyous arts of making-do and doing without. Straight and short is the line from all of that to a way of being in the world that lies peacefully beyond the seductions of the falsifiers and all their many falsehoods.

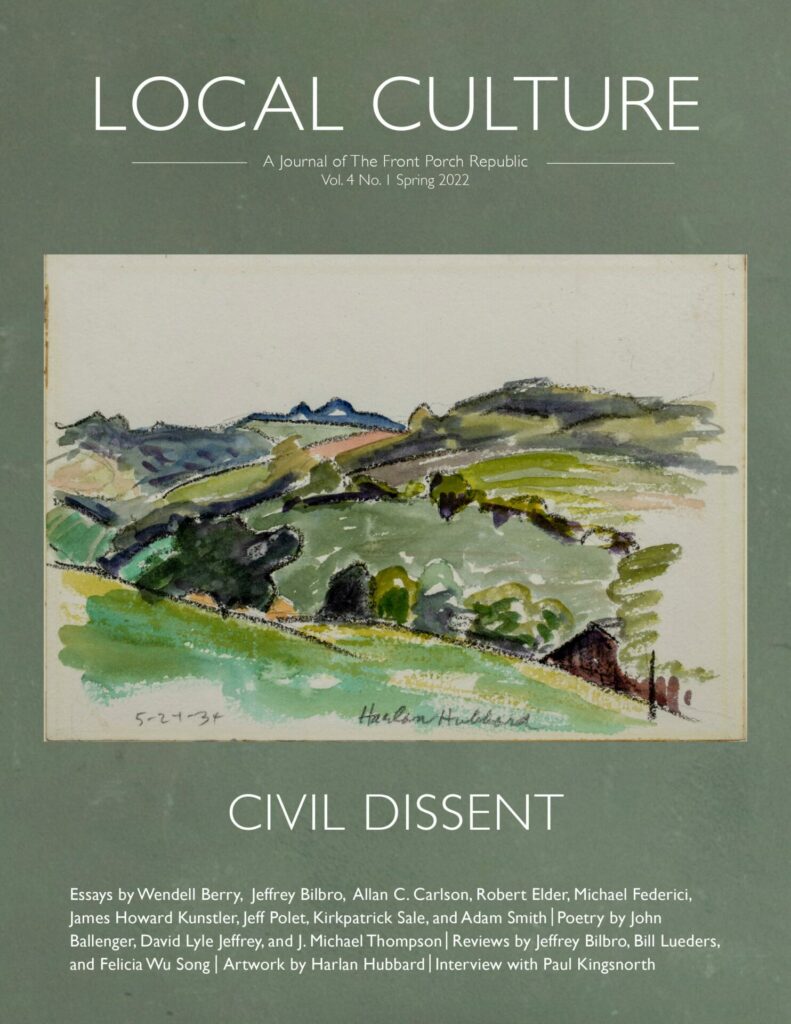

Think not, then, of the ubiquitous screens and hideous architecture and suburban metastasis and microwave dinners. Think rather of Eric Voegelin’s famous quip—Voegelin, who said that “no one is obliged to take part in the spiritual crisis of a society; on the contrary, everyone is obliged to avoid this folly and live his life in order.” Here Local Culture devotes its pages to versions of this ordered living, to calling out the folly that such living declines, by mere dint of what it is, to take part in, and to thinking for example of Harlan Hubbard, that quiet exemplar of ordered and artful living whose artwork graces the cover of this issue. Of this civilized civil dissenter Wendell Berry once said, “I knew a man who, in the age of chainsaws, went right on cutting his wood with a handsaw and an axe. He was a healthier and saner man than I am.”

4 comments

EJ

The differentiation and analysis of prepositions is just about my favorite thing in all the world.

Martin

Wow. Even Don Quixote chose which windmill to tilt at. He didn’t aim at all.

“Straight and short is the line from all of that to a way of being in the world that lies peacefully beyond the seductions of the falsifiers and all their many falsehoods.”

I agree, but the overwhelming “everything including the kitchen sink” style of this essay isn’t exactly straight and short, nor linear.

“Is there a more constructive use for what the fourth estate produces?”

Soak it in water and bring it to the outhouse?

Thomas McCullough

What is “Kirk’s mechanical Jacobin”?

Aaron

And a tip of the hat to you. Nicely bracing.

Comments are closed.