As a homeschooling mom, my mother enters a new era: that of not being a homeschooling mom. My youngest sister is a freshman in college, and the sun of the Clarke Homeschool has set. In loving memory of the past, my mom sent us kids the notes from her very first homeschool conference in 1998.

This conference was not only her first major exposure to the world of homeschooling but also her first exposure to classical education. Perusing her notes, I find “trivium,” “content,” “methodology,” and above these in capital letters, “GRAMMAR—LOGIC—RHETORIC.” As a former homeschool kid who made it out alive, talk of classical education is like white noise to me. Anyone with half a brain knows at least what the trivium is, nods knowingly at “the great books,” and confesses (if not believes) the essential place of Euclidean geometry. In 1998, however, my mother did not know these things. Her notes are an ebenezer stone, reminders of the first time she tasted what she wanted to feed her children.

My throat caught when I read one particular phrase: “I can’t do it all with my own kids. I have to think of my grandkids.”

As a nurse, my mom knew that she could not transfer the entire corpus of Western thought to us because she didn’t have it. But she did have love. She often told us that in nursing school, she was awestruck at God’s design when she studied the human ear— “I just cried. It was too incredible.” In deciding to homeschool us, she accepted that whatever she did was only the first step. As she learned more about classical education and homeschooling as a whole, she passed along whatever she reclaimed from the past.

My mom hadn’t spent her life sifting through select works of poetry, but she read it to us anyway. She hadn’t studied Plato and Aristotle, but she drilled beauty, goodness, and truth into us on the daily. She was no literary connoisseur, but she read Dickens. She didn’t know Latin, but she learned tidbits alongside us, proclaiming her favorite phrases at opportune moments: dum spiro spero (“while I breathe, I hope”), ora et labora (“pray and work”), mea culpa (“my fault”), and, to rally us on a slumpy school day, her fist raised resolutely in the air, EXCELSIOR! (“higher!”). Her eyes shone; ours rolled.

Children roll their eyes at good and true things out of intense ignorance. When they are faced by something good that they do not immediately perceive as delightful, they turn away, on the hunt for less demanding pleasures. Even if a child inwardly knows that it is good, they send their army of passions and vices to fend it off, rather than bravely welcoming it themselves. Children are a paradox; they are both stiff and pliable. They balk and squirm at the feast of life their parents lay before them, perceiving it as burdensome. Simultaneously, they delight in their own crude desires, bending wherever they please but unaware that service to self is the heaviest yoke of all. Their necks are stiff, and education serves as lubrication for another paradox: to look up toward the higher things and eventually bow before them in humility.

My mother’s educational efforts and dogged perseverance was lost on us—or I should say, lost on me. I recited poetry, but as flatly as I could muster. I chanted our grammar songs, but at a volume just above inaudible. I completed my cursive assignments, but resentfully, badly and—one time—in pen. Mom read to us and we would sit until—inevitably—she pinched the bridge of her nose, pursed her lips, and struggled through a touching passage. We would look at each other, sighing, and wonder, why does she have to cry?

The most memorable instance of this was on a sunny autumn morning in the living room. Propped in a chair with her Morning Time material scattered around her, mom was reading a novel to us, and the main character had just succumbed to the grace of God. Mom was gearing up to tear up. She pinched the bridge of her nose (etc.) and, overwhelmed, cried: “God could use anything in our lives to save us, he could use anything! He could use…”

To her left, on our fireplace hearth, sat a plump, glossy pumpkin. She thrust her hand toward the unsuspecting squash, spluttering, “He could use a PUMPKIN!”

We couldn’t help it. We laughed. But we laughed secretly believing she was right.

Education requires book learning and intelligence, but knowledge of higher things—what Michael Oakeshott calls practical knowledge—cannot be learned from a book, it cannot be memorized, it cannot even be taught. It is rather contracted, absorbed, tasted—one abides in it. This kind of knowledge is the salt that preserves civilizations and coaxes out the true flavor of a person. Practical knowledge lubricates the young yet rusty heart of a child. It is this knowledge that my mother practiced and passionately sought to infuse into her children.

What affects me so much about my mom’s notes from that conference long ago is that she practiced what she believed for twenty-six faithful years: she couldn’t teach her children everything, and so she had to think of her grandchildren. Thinking of her grandchildren spurred her on to give her children the best of what she had, trusting they would go further, giving their children the best of what they have. Mom didn’t read Plato and Aristotle, but because of her, I have; she didn’t learn much Latin, but because of her, I have. I now believe God could use a pumpkin, perhaps even more strongly than my mother believes it. Through her battle cry of excelsior, I have gone higher.

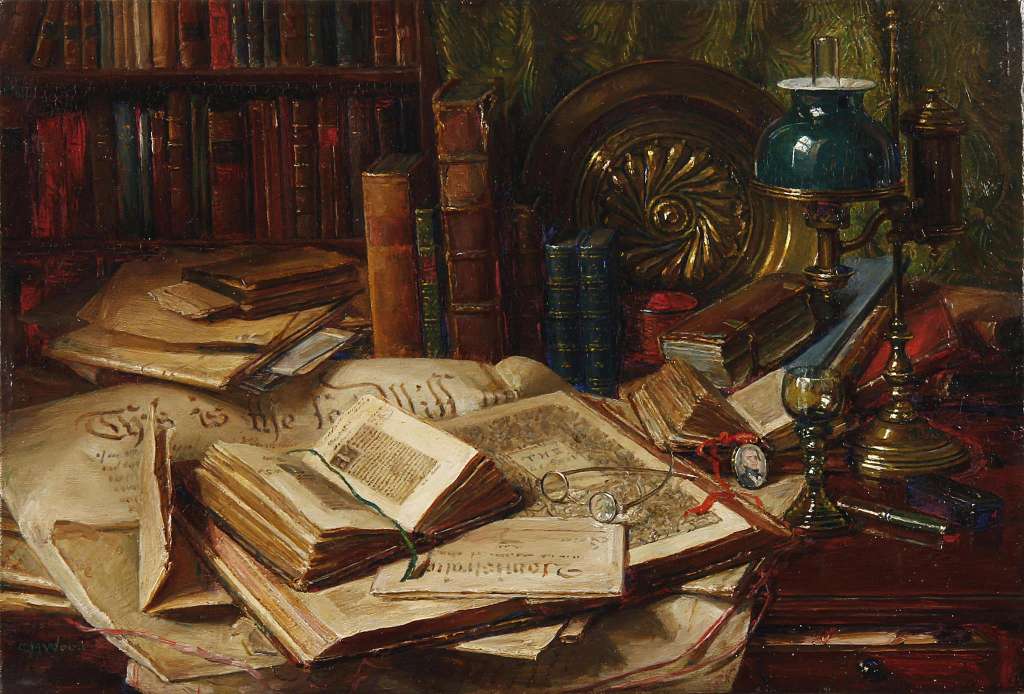

Image Credit: Catherine M Wood, “Old books” via Wikimedia