When I speak with the college students in my philosophy of love courses about relationships, what I hear again and again is fear. Fear of dating, fear of commitment, fear of vulnerability, fear of anything costly and irrevocable. Casual hookups and situationships abound, and young people are regularly warned against “catching feelings.” And it’s not just Gen Z. The number of U.S. adults shying away from dating and marriage has been hovering around record highs. I can sympathize. I’ve often wished for a “do-over” when I try something risky and fail. But that isn’t what life offers us. The risks are real and so are the consequences. Yet the response to this reality shouldn’t be to retreat to safety, but to take up a heroic or romantic stance towards our lives and especially our loves.

By “romantic,” I don’t mean the flush at a glance, the flutter of excitement at a touch, or the feeling of infatuation at the thought of one’s beloved. The Oxford English Dictionary tells us that, originally, “romance” referred not to a feeling or a love affair but a narrative—the adventure of a hero. Over time, the term came to denote a quality that “appeal[s] strongly to the imagination, and sets it apart from the mundane” and was associated with wonder and mystery. Eventually “romantic” was used to allude to an atmosphere or mood appropriate to such stories of adventure: idealistic, sentimental, and dramatic. It was only in the mid nineteenth century that “romance” narrowed to its recognizably modern form, indicating a love affair and its corresponding passions.

My proposal is that we should hear the older resonances in the word “romance.” This would help us understand our love affairs properly and grasp the heroism they demand of us. If romance is essentially an adventure, then we should expect love to have several interrelated features: risk, commitment, and drama.

Risk. Romance requires giving up the illusion of control. In an adventure, one is not so much at the wheel as along for the ride. Perhaps the fundamental feature of adventure is not knowing how it will turn out. The medieval stories of knights were romantic in part because they encountered real danger. What makes the story of Prince Charming fighting the dragon to rescue Sleeping Beauty romantic is that the Prince might just get killed. In this sense, having a child is romantic—it could change your life. So is going to war—it could end it. Getting married is romantic, even more romantic than “falling in love,” precisely because it is indelible.

Romance requires exposing yourself to unpredictable events that may make your life immeasurably better or immeasurably worse. When it comes to relationships, one must be willing to risk rejection and unrequited love. In The Four Loves C.S. Lewis wrote, “To love at all is to be vulnerable. Love anything, and your heart will certainly be wrung and possibly be broken.” Even when one’s bid for love is successful, one faces the inevitability of loss and grief. To paraphrase Colin Murray Parkes, grief is the price we pay for love. At the same time, “Faint heart never won fair lady.” The paradox of life is that it’s the person who is willing to lose their lives that will find it. Only the hero that is willing to risk suffering can win love.

Commitment. Romance requires being all-in. An adventure you can call off half-way through is no adventure. This fits uneasily with our liberal societies, which prioritize autonomy, self-expression, and self-realization. We’d prefer to think that relationships—even marriages—are essentially two people on their own journeys whose paths may overlap for a time. Each reserves the right to leave if they have a better option. Hence, there is decreasing space in the modern imagination for thinking of love and marriage as something romantic—that is, as dramatic, risky, and irrevocable. Yet the desire to be in control with both feet firmly on the ground makes it hard to be swept off our feet. As Robert Johnson pointed out in his wonderful book, We, the avoidance of commitment gives many modern relationships a “provisional quality”—they can generate a temporary frisson of infatuation or passion, but they are utterly devoid of romance.

Drama. One might argue that if romance requires drama, then commitment is the death of romance, and one should avoid it. As Denis de Rougemont pointed out nearly a century ago, romance in the narrow sense of feeling or passion thrives on absence and obstruction, not intimacy and familiarity. That the lovers in Tristan and Iseult and Romeo and Juliet could never be together was not a bug; it was a feature. But this means that the desire for a perpetual state of infatuation is a desire for the absence, not the presence of the beloved. Such “love” is, in fact, only self-love. Passion which is directed at the beloved, rather than the self, drives the lover to be united with the beloved, even if this means the death of passion itself. Commitment is the dramatic act of passion sacrificing itself in the hope of being resurrected as a love which is more stable and durable—a lifelong love.

Married life itself is dramatic, though we usually lack the perspective and sense of scale to see it. An adventure is no less an adventure despite consisting mostly of mundane tasks like eating and sleeping. Similarly, the drama of marriage resides primarily in the narrative arc. From “boy meets girl” to… no one knows. Where before marriage obstacles may have prevented the lovers from being together, now they reemerge to rend them apart. Where previously competing suitors may have made the intense value and desirability of one’s beloved obvious, now familiarity has dulled our sense of the splendor of the immortal being whom God has put into our arms. The drama of marriage lies in sharing life with someone—facing the unknown with all its joys and tribulations. So far from being the death of romance, commitment is its apotheosis—it inaugurates the adventure of sharing one’s life with someone. Passion that never leads to commitment, that never goes “all-in,” and never risks itself to have the beloved is profoundly unromantic.

As the relationship recession deepens and spreads, it’s entirely possible that many will give up the danger and drama of a human relationship, turning instead to the safety and predictability of technology, like an AI companion. Troublingly, if romance requires risk, then our “safety-first” culture will become increasingly incapable of romance. Rather than giving in to fear, we should face the uncertainty of life bravely. To live is dangerous, to love more dangerous still. Both call for heroism.

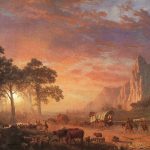

Image Credit: Louis Hovey Sharp, “Valley in the Mountains” (1930s) via Wikimedia