Queens, NY

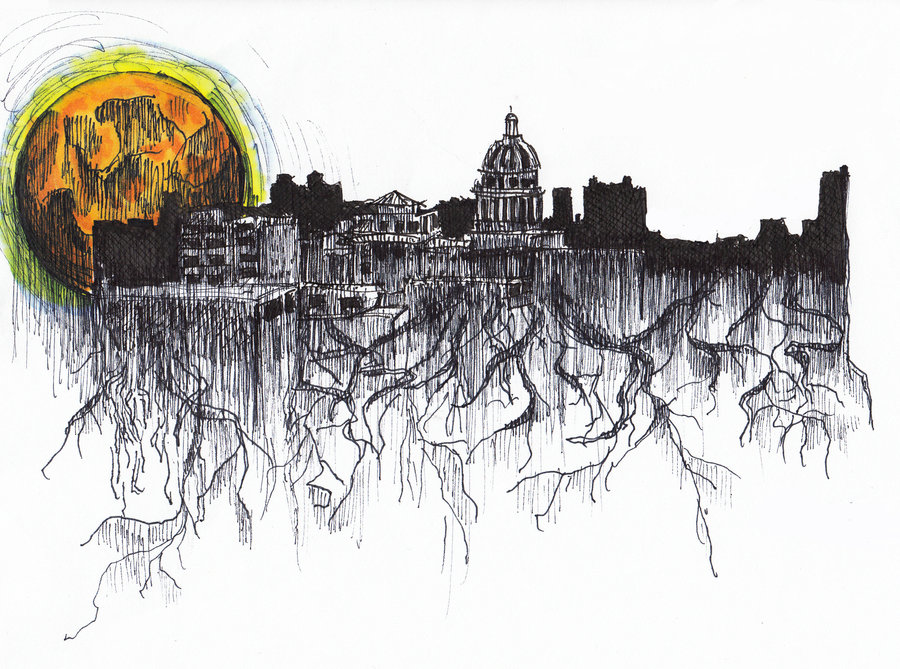

Under ordinary circumstances, with very few exceptions, it is these crews that do the actual work of the city. And under extraordinary circumstances, it is they that bring a city through crisis. “Citizens,” said Althusius, “contribute their services in guarding and defending the city.” We do not do this now; we have police instead. But these groups seem, in times of crisis, to reemerge. A city, in danger, does not become one big family; it becomes a network of crews: shoulder to shoulder they rebuild.

In a piece covering the Congress for the New Urbanism’s recent meeting, Jon Coppage writes of the Detroit neighborhood of North Rosedale, describing how, during the 1980’s, “Devil’s Night arsons would light the city in every direction every Halloween Eve;” but he describes too how it was “the residents who put out those fires, and starting in 1995, 50,000 citizens walked the streets to protect their neighborhoods from being burned by vandals.” These volunteers, organized into neighborhood-level groups, are eminently crews.

Michael Sorkin, in his essay “Urban Warfare: A Tour of the Battlefield,” identifies the “crisis conviviality” that typically overtakes New York when crises happen. “Since 9/11,” he says, “we have a new paradigm for responding to breakdowns in the urban infrastructure and we deployed it with fine results during the power outage. Pedestrians took over the streets and sidewalks, walking home and enjoying continuous linear socializing. Outside every bar and bodega, a crowd gathered– it was almost cocktail time when the power went out, but the mood was upbeat. The timing couldn’t have been better…The city was “paralyzed” but we enjoyed the opportunity to display our civil solidarity, and to use the disaster to temporarily expand the territory of public space, “appropriating” the street like a closing of a street fair.”

This is a spontaneous manifestation of the social and celebratory version of the crew– and the formalized version of this celebratory aspect of the life of crews was part of the collegial tradition that Althusius described. I mentioned, above, that Althusius said that as well as exchanging goods, services, and “common rights,” members of a collegium also exchange “mutual benevolence,” which is ”that affection and love of individuals toward their colleagues because of which they harmoniously will and ‘nill’ on behalf of the common utility.” And here we come to one more of those places where Althusius’ description of properly political, though private, relation that members of a collegium have with each other becomes very strange again, a note sounding out of another world: This benevolence, he tells us, “is nourished, sustained, and conserved by public banquets, entertainments, and love feasts [conviviis, convictu & agapis publicis alitur.]”

This phrase, love feasts, agapis, is the latinized version of the Greek word used in New Testament to refer to the meal at which Communion was celebrated. This is a strange usage indeed; what he is referring to may be something parallel to what Joanna Picciuto describes in her Labors of Innocence in Early Modern England:

“…through the weekly ritual of “holy bread,” parishioners were able to perform a mild reassertion of the unity of the corpus verum and corpus mysticum. Taking turns to provide the weekly loaf, which was blessed but not consecrated and then shared at the church door, they formalized the line that made the working community a community of companions, bread sharers. For some, this moment was extended by the communal guild feast, which followed upon the mass and became a “paraliturgical” institution in its own right … the link between communion and labor asserts itself in the institution of a ”love feast” that began at the church door and continued into the guild hall…Guilds and craft fellowships also provided a vehicle for the Adamic language of equal fellowship: in the corporate idiom of the guild, all members were united by oath to form a collective body…At feasts, guild members gave themselves over with abandon to the language of love, affective bonds for which industry formed the matrix. Guests from neighboring trades were frequently invited to these feasts; because of the collective conditions of artisanal labor, good relations across the trades was essential. Like a sown field, the construction of an everyday object like a saddle was a collective achievement, the product of coordinated effort of saddlers, joiners, lorimers, and painters. Love feasts were occasions to consecrate the cooperative labor that held the corpus mysticum together.”

These corporate dinners are, then, things that are are the civic parallels, essentially, to the Eucharist; feasts of some kind, at least, are as much a part of the nature of a corporation, in Althusius’ view, as its legal structure and its exchange of goods and services.

Group friendships are formed in crisis, and existing friendships come into their own, become networks for the distribution of water, emergency supplies, and information. In the days after the Great Fire of San Francisco, the city’s three main papers, having hauled some of their presses outside the perimeter of danger, ganged together to put out several issues in collaboration– journalists and editors and typesetters working side by side with their rivals.

Even the everyday work of crews– that not specifically aimed at rebuilding the city or defending it, but simply at carrying out ordinary activities– takes on a different flavor during a crisis. New Yorkers keep calm and carry on, and do it with a kind of defiance and panache; for the sake of the private good of the crew and, as a crew, for the public good of the city. And everyday life becomes something more, and the City, which had seemed ordinary, becomes something more; we see in these moments something like the veil lifted, as we refuse to revert to an every-man-for-himself state of barbarism.

And this attitude persists even as, in Sorkin’s description, “the city is remapped in terms of its potential for disaster, its strategic locations revealed as a series of target[s],” as “high value targets are hardened with Jersey barriers, security cameras, armed guards,” and choppers overhead. It is in the face of the militarization of New York that New Yorkers keep seeing it as a source of joy and abundance and sarcasm and gelato. And this vigilance, this awareness, doesn’t work against it– it can, just as many aspects of a disaster can, be a source of increased conviviality, increased delight.

This way of being a New Yorker kicked in once again several weeks ago, in a very very mild way, when, late at night, I got a text from a friend. “Some kind of explosion in Manhattan while we were watching the movie.” This was the Chelsea bombing, and over the next few days the usual drawn-out aftermath happened: the first responders, the assumption that it was ISIS, the accusations of racism at those who assumed it was ISIS, the accusations of PC blindness at those who accused the ISIS assumers of islamophobia, the text messages to be on the alert for the guy with a Muslim name, the manhunt, the stash of propaganda.

And in the interstices of this, there was life: I went to church on Eleventh Street on Sunday, walked up to Twenty-first before that, stood aside for a firetruck, took in the calm, laconic work of the NYPD, texted another friend about brunch plans, ending politely with “I hope you’re not exploded?” (He was not,) took the F uptown after church with two more friends as we talked about the impossibility of stopping life just because there’s been another attack.

“I mean it’s not like I even considered not coming to church,” I said to one of the two I was with on the subway, and he hadn’t even considered not going to church either, or not going to teach his class at Bard afterwards; no one considered cancelling the brunch that the other friend and I were going to; it was Frater Urban Hannon’s last day in the city and we sat around eating toad-in-the-hole and potatoes and bacon and talked about Thomism and the game of Diplomacy we want to organize, and the two-year-old who belonged to two of the brunchers kept picking pieces of bacon off the serving plate and offering them to people, saying “Meat! Meat!” and then we all went to Vespers at St. Vincent Ferrer and the two-year-old was in the choir stalls with us as we chanted, and in between the chanting we could hear her clear voice saying, contemplatively, “Meat! Meat!”