Buffalo, NY. In 2019, Elizabeth Grant, who performs as Lana Del Rey, released her fifth studio album, Norman Fucking Rockwell! (NFR!). Described in Rolling Stone as “even more massive and majestic than everyone hoped it would be,” NFR! earned Del Rey two Grammy nominations and inclusion on multiple “Best of 2019” lists—one of which eventually led me to her album. One track stood out to me. In “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have—but i have it,” Del Rey reflects provocatively on the intersections of happiness, sadness, fame, depression, fear, and hope. This song could easily be an anthem for our times.

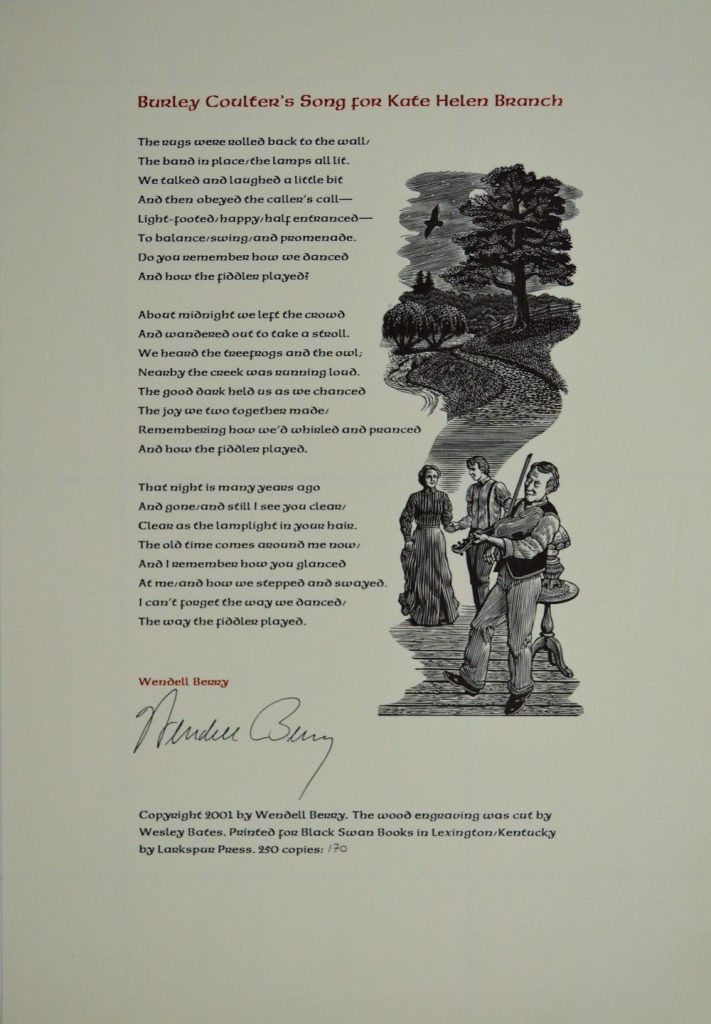

In 2005, the Kentucky poet Wendell Berry published “Burley Coulter’s Song for Kate Helen Branch.” Readers of Berry’s Port William stories will recall the jokester Burley and his lover, the mother of Burley’s son. Now old, Burley fondly recounts an evening of whirling and prancing with Kate Helen. “I can’t forget the way we danced.” Burley says, “The way the fiddler played.” Perhaps because Larkspur Press also published the poem alongside a Wesley Bates engraving, these words always elicit in me a vivid image of the couple dancing through the night, with and without musical accompaniment. These images join youth, old age, and the hope of love.

In 1982, Stephen King published Different Seasons, a collection of four novellas. Radically different than his earlier horror fiction, such as Salem’s Lot, Carrie, and Firestarter, the stories were well-received. Three of them were recast for the big screen. Perhaps the most acclaimed was the adaption of “Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption,” which recounts the incarceration and ultimate deliverance of Andy Dufresne after his wrongful conviction for double murder. People love this movie, evidenced by its repeated appearances on American Movie Classics and its inclusion near the top of multiple lists of the greatest movies of all time.

Lana Del Rey. Wendell Berry. Stephen King. Singer-songwriter. Poet-novelist-essayist farmer. Horror writer. What brings these three seemingly disparate artists together in my imagination? Hope.

As I write these words in April 2020, in the middle of a global pandemic, hope is certainly something we need. On the morning of April 17, more than 2.2 million people had been infected globally with 150,948 deaths. In the United States, April 16 marked the highest single day of deaths so far as 4,591 American men, women, and children succumbed to the novel virus. By month’s end, even with all the shortcomings in our testing apparatus, more than 1 million Americans had tested positive. As of April 28, the number of Americans who had died from COVID-19 (58,365) outnumbered Americans deaths during the Vietnam War (58,220). April 28 also marked three weeks since the passing of songwriter John Prine, a man of hope (as seen vividly on his last album The Tree of Forgiveness). Yes, hope is a virtue worth pursuing in these days. But not only in these specific days. Regardless of the circumstances, I believe hope, while dangerous, remains a good thing, maybe even the best thing, as perhaps a little dancing alongside Wendell Berry and Lana Del Rey—with Stephen King on the fiddle (if not his more familiar guitar)—will demonstrate.

Del Rey’s “hope is a dangerous thing for a woman like me to have—but i have it” follows a woman who, though clearly not happy, declares she is not sad. She knows that with all the things in her life causing stress and pushing her toward depression, perhaps she would be better off simply giving up. The trappings of her life, though, seemingly make such a decision impossible. Her painful memories, flirtations with celebrity, and reflections on the divine seem both to confuse and to clarify, leaving her dangling between the inevitability of despair and the possibility of hope. She certainly knows that holding on to hope likely prolongs her distress, and maybe even endangers her and those around her. Nonetheless, after her final insistence about the perils of hope, she ends the song: “But I have it. Yeah, I have it. Yeah, I have it. I have.”

Del Rey’s lyrical focus on this troubled dance with hope reminded me of an exchange in Shawshank Redemption. When Andy Dufresne, the protagonist, gets out of solitary confinement for playing Mozart over the loudspeaker from the warden’s office, he joins his fellow inmates in the dining hall and has a brief conversation with his friend Ellis Boyd “Red” Redding about the need for things like music. Andy tells Red that music keeps one from forgetting “that there are places in the world that aren’t made out of stone. That there’s something inside that they can’t get to, that they can’t touch. It’s yours.” That something, according to Dufresne, is hope. Red’s reply to Andy, then, is what Del Rey’s lyrics brought to my mind. “Let me tell you something, my friend,” he says. “Hope is a dangerous thing. Hope can drive a man insane. It’s got no use on the inside. You better get used to that idea.”

For most of the film, however, he doesn’t. This fact is perhaps even more clearly illustrated in the novella the film adapted, King’s “Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption.” Dufresne, like Del Rey, refuses to give up and accept defeat, despite having nearly every reason to do so. In 1948, after deliberating for less than three hours (and only that long in order to get “a nice chicken dinner”), a Maine jury found Dufresne guilty of murdering his wife and her lover. Over the next twenty-seven years, Dufresne negotiates life behind bars. He navigates his way through numerous sadistic wardens and guards, fellow inmates looking to establish their place inside the prison walls, and stints in solitary isolation. Both the novella and the film give many reasons Dufresne could have given up any hope of proving his innocence.

Fifteen years into his incarceration, Dufresne seems to do so. After learning from a fellow inmate, Tommy Williams, that a convict in another prison had confessed to the murders, Andy approaches Warden Norton with his newfound information, expecting the warden to support his effort to clear his name. But Norton relies on the former banker’s financial acumen to commit fraud. So, he refuses even to “make a single long-distance call” to verify the facts. Instead, he places Dufresne in solitary confinement for twenty days. When Andy gets out, Norton informs him that Williams has been transferred to a different facility. Stunned, Andy asks why. “Because people like you make me sick,” the warden replies, “You see, you used to think that you were better than anyone else. I have gotten pretty good at seeing that on a man’s face. I marked it on yours the first time I walked into the library.” “That look,” Norton continues, “is gone now, and I like that just fine….you don’t walk around that way anymore. And I’ll be watching you to see if you should start to walk that way again.” Andy responds by threatening to stop aiding Norton with all his “extracurricular activities,” which earns him another stint in solitary—this time for thirty days. Afterward, according to Red, “Andy Dufresne had changed.”

For the next several years, Andy seems to believe, like Red, that hope’s “got no use on the inside.” Then, in October 1967, Andy sits down with Red to tell him of his plans to run a little hotel on a beach in Mexico. Andy reveals to Red that he’s the sort of guy “who knows there’s no harm in hoping for the best as long as you’re prepared for the worst.” For Andy, this preparation and hope is based on action. Through a friend he’s had an alias, Peter Stevens, established. The friend has placed all the necessary documents for his new life in a safe deposit box, along with eighteen thousand dollars’ worth of unregistered bonds, and left the box’s key hidden in a hay field in the little town of Buxton, Maine.

Then, no more conversation about such plans. And, on March 12, 1975, no more Andy Dufresne. Or at least not in Shawshank. He disappears into a hole in the wall behind a poster of Linda Ronstadt (she had been preceded through the years by Raquel Welch, Hazel Court, Jayne Mansfield, Marilyn Monroe, and Rita Hayworth). Nearly six months to the day later, Red receives a blank postcard mailed from the border town of McNary, Texas. No more than a postcard. Maybe.

In 1977, after thirty-seven years, the prison board grants Red parole. He struggles to adjust to life outside the prison’s walls, finding everything “strange and frightening.” Thus, he begins contemplating ways to break his parole to get back inside. He is living a life without hope. Until he decides to grab a compass and hitchhike to the nearby town of Buxton to walk through some hay fields. “A fool’s errand,” he calls it. But one that ends with a rock, an envelope, a letter, and a thousand dollars. Hidden hope. In a hay field.

In a hay field is precisely where one might expect to find Kentucky writer, Wendell Berry. Author of more than sixty books, including novels, short stories, poems, and essays, Berry, a farmer, knows a few things about fields and fences. And he has written about both. He also knows and has written a few things about hope. In fact, Berry may well be one of the most hopeful writers of the last sixty years. Though he insisted in his 2012 Jefferson Lecture that affection or love is the centering and primary motive for good and proper care and use, he doesn’t maintain it is only affection that matters or motivates. Faith (coming alongside good works—since faith without works is dead), hope, and love are all central to Berry’s thought. “Affection,” he asserts, “leads by way of good work, to authentic hope.” Throughout his poetry, essays, novels and even in recent interviews, Berry has constantly emphasized the importance of the virtue of hope.

Berry has certainly lived through hope-shaking times. His poetry has consistently been a place where he has addressed the needs of those times. For extraordinary moments, he penned poems like “November 26, 1963,” which addressed the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, or “Against the War in Vietnam.” But Berry more regularly addresses the need for virtue in ordinary moments, often connecting hope with faith and love. In “The Plan,” published in 1964 in The Broken Ground, his first volume of poetry, Berry treats the theme of friendship in verses that have two old buddies scheming for a fishing trip together.

My old friend, the owner

of a new boat, stops by

to ask me to fish with him,and I say I will—both of us

knowing that we may never

get around to it, it may beyears before we’re both

idle again on the same day.

But we make a plan, anyhow,in honor of friendship

and the fine spring weather

and the new boatand our sudden thought

of the water shining

under the morning fog.

The two men share a faith in sharing time together. As they plan a future day together, faith engenders hope. And such hope honors their friendship.

In 1969, Berry published Findings, another collection of poems. One of the longer works in Findings is again an exchange between two people. This time, in “The Handing Down,” the conversation is between a grandfather and his grandson. As the grandfather shares the history of their community while entering into community with his grandson, he relies on some familiar virtues. They share patternless conversations because of “a shaped knowledge / in the minds of the two men / who love each other.” The older man’s faithfulness to the region and its people have ensured that he “has become one of the familiars / of the place, like a landmark / the birds no longer fear.” This love and faith comfort him, providing hope. Even as he experiences moments of doubt when it seems as if all hope and any reason for hope is gone, the grandfather trusts (has faith in) the fact that “failed hope / doesn’t prove the failure of hope.” In fact, it “is a comfort of sorts.” Through their sharing, the grandson learns this truth, as well. As he thinks of his grandfather, the younger man “is comforted, not because he hopes / for much, but because he knows / of hope, its losses and uses.”

Many of his essays written around the same time also illustrate Berry’s reliance on hope. The same year that Findings appeared, Berry published The Long-Legged House, his first collection of essays. While he treats the theme in several essays in this collection, the two focusing on Vietnam clearly foreshadow how important hope will remain in Berry’s thinking. In “A Statement Against the War in Vietnam,” he addresses the possibility of peace, which he finds “a better possibility than the possibility of war.” Making it clear that he grasps the difficulty of such a prospect because of the tendencies of humanity, Berry states that he will not be optimistic, but “I will be steadfastly hopeful, for as a member of the human race I am also in the company of men, though comparatively few, who through all the sad destructive centuries of our history have kept alive the vision of peace and kindness and generosity and humility and freedom.”

In Berry’s calculus, such hopefulness is only possible if “we make ourselves better men.” As he writes in another essay about citizenship and peace in that same volume, such a possibility from humans “holds out to me in the most immediate way the hope of peace, the ideal of harmlessness, the redeeming chance that a man can live so as to enhance and enlarge the possibility of life in the world, rather than to diminish it.” This hope isn’t a given, of course. In fact, it isn’t even easy. “Peaceableness,” Berry writes, “and lovingness and all the other good hopes are exactly as difficult and complicated as living one’s life, and can be most fully served in life’s fullness.” Difficult and complicated. But fully possible.

In his effort to make himself a better man, Berry sometimes writes poems on his Sunday morning walks. These Sabbath poems, as he calls them, very often delve into reflections or meditations on various components of religion and Christian theology. Thus, it’s no surprise that Christian virtues show up regularly. In the 2007 Sabbath poems, for instance, faith, hope, and love are common themes. On the subject of hope, several of these works, such as “III,” stress the difficulty of maintaining that virtue. “Yes,” Berry writes, “though hope is our duty, / let us live a while without it / to show ourselves we can. / Let us see that, without hope, / we still are well. Let hopelessness / shrink us to our proper size. / Without it we are half as large / as yesterday, and the world / is twice as large. My small / place grows immense as I walk / upon it without hope.”

In “VI,” another poem from that year, Berry again laments the struggle to hope, but he also locates one of the primary places where one can find reason to hope. “It is hard to have hope,” he writes, “It is harder as you grow old, / for hope must not depend on feeling good / and there is the dream of loneliness at absolute midnight. / You also have withdrawn belief in the present reality / of the future, which surely will surprise us, / and hope is harder when it cannot come by prediction / any more than by wishing. But stop dithering. / The young ask the old to hope. What will you tell them? / Tell them at least what you say to yourself.” And, for Berry, the thing that first should be said to self is that one’s place matters and should receive affection. Such a love for one’s place leads to hopeful care. “Hope / then,” Berry writes, “to belong to your place by your own knowledge / of what it is that no other place is, and by / your caring for it as you care for no other place, this / place that you belong to though it is not yours, / for it was from the beginning and will be to the end.” Such a hopeful care for one’s place leads to an even fuller hope:

Found your hope, then, on the ground under your feet.

Your hope of Heaven, let it rest on the ground

underfoot. Be lighted by the light that falls

freely upon it after the darkness of the nights

and the darkness of our ignorance and madness.

Let it be lighted also by the light that is within you,

which is the light of imagination. By it you see

the likeness of people in other places to yourself

in your place. It lights invariably the need for care

toward other people, other creatures, in other places

as you would ask them for care toward your place and you.No place at last is better than the world. The world

is no better than its places. Its places at last

are no better than their people while their people

continue in them. When the people make

dark the light within them, the world darkens.

The connection between place and hope remains strikingly consistent in much of what Berry contends in his essays. “And those days that gave me peace,” he wrote nearly forty years earlier in The Long-Legged House, “suggested to me the possibility of a greater, more substantial peace—a decent, open, generous relation between a man’s life and the world—that I have never achieved; but it must have begun to be then, and it has come more and more consciously to be, the hope and the ruling idea of my life.” Hope might get harder through the years, but Berry’s formula for it still sustains him.

In his fiction, Berry illustrates the difficult, perhaps dangerous, and certainly good thing of finding such hope. Since an extended examination of the theme of hope in the stories of Port William would easily take on a life of its own, I simply want to look briefly at the importance of the idea in two of his novels, Hannah Coulter and Remembering.

Hannah Coulter’s story in the Port William mythology is saturated with hope. The daughter of Dalton and Callie Steadman from the neighboring town of Hargrave, Hannah is first introduced to Port William in A Place on Earth (1967) when she marries Virgil Feltner. She then loses her husband in World War II. Once she and the community accept his death, Hannah slowly and faithfully develops a relationship with Nathan Coulter, who had also served in the war. Eventually, the two marry and assume significant roles in the Port William membership. Published in 2004, Hannah Coulter recounts the memories of the almost octogenarian—her “giving of thanks.” Situating herself within the larger stories of the membership, Hannah tells of her life, focusing on her grief, her successes, her failures, her losses, her family, her friends, and her place. Through all her experiences, hope abides. “Living without expectations,” she reflects, “is hard but, when you can do it, good. Living without hope is harder, and that is bad. You have got to have hope, and you mustn’t shirk it. Love, after all, ‘hopeth all things.’ But maybe you must learn, and it is hard learning, not to hope out loud, especially for other people. You must not let your hope turn into expectation.” Such an expectation, in Berry’s estimation, is more in line with optimism. But hope, unlike optimism, remains.

In 1988, Berry begins his novel Remembering with two important statements on hope. First, he dedicates the book to his friends Ed McClanahan and Cia White with an excerpt from Ecclesiastes 9:4: “to him that is joined to all the living there is hope.” Then, he includes the following petition in the form of a poem:

Heavenly Muse, Spirit who brooded

The world and raised it shapely out of nothing,

Touch my lips with fire and burn away

All dross of speech, so that I keep in mind

The truth and end to which my words now move

In hope. Keep my mind within that Mind

Of which it is a part, whose wholeness is

That hope of sense in what I tell. And though

I go among the scatterings of that sense,

The members of its worldly body broken,

Rule my side by vision of the parts

Rejoined. And in my exile’s journey far

From home, be with me, so I may return.

By including these two selections (along with one about love) in the front matter of the novel, Berry prepares his readers for the tale that follows.

Remembering tells the story of a single day in the life of Port William’s Andy Catlett. Andy, a farmer and agricultural writer, is facing a crisis of identity after losing his right hand in an accident on his farm. Separated literally and figuratively from his family, his wife, his dreams, his home, Andy is seemingly without hope. As he walks around San Francisco, though, Andy remembers. His memories of those things from which he is exiled bring Andy back—not only to himself, but ultimately to his place in life and to his place within the membership of his community. This re-membering wasn’t a given. Andy had to choose it. And it was a choice made out of hope—his own hope and the hopes of others.

He thinks of the long dance of men and women behind him. Most of whom he never knew, some he knew, two he yet knows, who, choosing one another, chose him. He thinks of the choices, too, by which he chose himself as he know is. How many choices, how much chance, how much error, how much hope have made that place and people that, in turn, made him? He does not know. He knows that some who might have left chose to stay, and that some who did leave chose to return, and he is one of them. Those choices have formed in time and place the pattern of a membership that chose him, yet left him free until he should choose it, which he did once, and now has done again.

Andy’s realization of those choices and his place in that membership remind him of a hope he’d enjoyed before, though maybe he had never taken joy in it before. Now he can. Now he does. When asked on the flight home if he is all right, Andy replies, “Yes. I’ve been all right before, and I’m all right now.” In the end, those hopes and choices, dangerous though they were, led Andy back to his wife, his family, his farm, his place, and himself.

Seeing the significance of hope for Andy Catlett and Hannah Coulter shouldn’t surprise Berry’s readers. And when asked about the subject of hope, his answers often reflect the experiences of Andy, the character who often mirrors Berry most clearly. For example, in a 2014 interview with Yale Environment 360, Berry addressed why he prefers the language of hope over that of optimism. His answer sounds much like the Andy found at the end of Remembering.

The issue of hope is complex and the sources of hope are complex. The things hoped for tend to be specific and to imply an agenda of work, things that can be done. Optimism is a general program that suggests that things are going to come out swell, pretty much whether we help out or not. This is largely unjustified by circumstances and history. One of the things that I think people on my side of these issues are always worried about is the ready availability of cynicism, despair, nihilism — those things that really are luxuries that permit people to give up, relax about the problems. Relax and let them happen. Another thing that can bring that about is so-called objectivity — the idea that this way might be right but on the other hand the opposite way might be right. We find this among academic people pretty frequently — the idea that you don’t take a stand, you just talk about the various possibilities.”

This passage sounds strikingly similar to a portion of a conversation Berry had at Yale University. In preparation for Berry’s 2013 Chubb Fellow lecture, Jeffrey Brenzell, then head of Timothy Dwight College, asked Berry how he sustained a sense of optimism. Berry replied that he’d be a fool to be an optimist and that instead he lived on hope, a very different thing from optimism. Asked to explain this idea a bit more, Berry stressed that he optimism and pessimism are reductive programs with predetermined ends. Hope, however, is about the “reality of good possibilities,” including the “possibility that you can do better.” Optimism leads to talking and waiting. Out of faith and love, hope acts.

Right now, in the spring of 2020 (and most likely for the foreseeable future), there isn’t too much about which one ought to be optimistic. Believing that the future promises to be swell isn’t always easy—what with the daily news briefings about the coronavirus (or at least the ones from Washington DC), the need to wear a mask to go to the grocery store in order to attempt to purchase toilet paper, or the loss of artists like John Prine. Thankfully, though, hope is something different. Hope, as Berry maintains, is “the opposite of despair.” It’s that reliance on the reality of good possibilities that has one walking hay fields and finding an envelope with a letter and some money under a specific rock.

In hope, Del Ray accepted the danger. In hope, Andy Catlett embraced “the long dance of men and women behind him.” In hope, Andy Dufresne/Peter Stevens encouraged his friend Red to join him in a town in Mexico, reminding him “that hope is a good thing, Red, maybe the best of things, and no good thing ever dies. I will be hoping that this letter finds you, and finds you well.”

Red remembers the name of the little Mexican town, Zihuatanejo. And he decides to violate his parole to get there, knowing he must either get “busy living or get busy dying.” And the ability to make that choice comes down to something else he learned from Andy Dufresne over the years.

“I hope Andy is down there.

I hope I can make it across the border.

I hope to see my friend and shake his hand.

I hope the Pacific is as blue as it has been in my dreams.

I hope.”

6 comments

Mark Haas

Richard,

Just a simple note to say thank you. Your essay is deep and rich and plentiful like the Good Earth. I read it with tears and joy and peace. And I ended it with hope: with renewed and bountiful hope.

with many thanks,

Mark

Richard A. Bailey

Thanks you so much for sharing this encouraging comment with me, Mark. I am grateful.

Anthony Oughton

I read Different Seasons as a teenager, Berry as soon to be family man in my thirties, and appreciated your article. I also thought of the story that became ‘Stand by Me’ and the hope of friendship, as well as Eric Miller’s book on Christopher Lasch.

If Dr House looks back this way, I valued your book on Bonhoeffer, and wondered if you had got around to doing something on liberal arts education as hinted at in the beginning of the book on seminary.

Finally, I write from England – there must be other front porch visitors here, and I wonder how we might connect.

Richard A. Bailey

Thank you, Anthony. I agree with you completely on Paul’s work (and will make certain to draw his attention to it).

Paul R House

This is good work by a good man on an essential topic. I am not sure what Norman Rockwell would think, but I like this piece.

Richard A. Bailey

Thank you, my friend, for this comment here, as well as your regular comments in my life.

Comments are closed.