A new issue of Local Culture: A Journal of the Front Porch Republic is heading to the printer. Below, you can read the editor’s prefatory letter. The Table of Contents can be viewed here. If this whets your appetite, you can subscribe to the journal; subscribe by Monday May 8th to receive a copy of this issue in your mailbox.

Perhaps you amuse yourself by imagining that the Ilium of good eating and drinking, long under siege, has finally fallen. The Trojan mare has spilled out all the chain restaurants and fast food secreted within her. She’s been delivered of microwaveable chicken alfredo and frozen pizzas and the plastic packaging it comes in. The home kitchen, once a festive leisurely place awaft with garlic and onion, amply provisioned with cocktails préparatoire and alive with bodies playfully bumping to the music as a white-wine reduction slowly thickens, has been breached at last, its pass-through set ablaze, its larders leveled by the brutish meat-headedness of the “food economy” and its vulnerable systems of transport. The old communal regard for pastured animals and nature’s law of return has been Haber-Bosched into oblivion. Smoke rises. The sunset over the backyard grill is as colorless as an aluminum fishing boat.

And perhaps you imagine hopefully, as I do, that at the moment of collapse your children prove worthy of their upbringing and refuse the proffered forkful of Soylent Green. They have been properly schooled after all and they take you on their shoulders, together with the household gods of skillet, roux, and rocks glass, to settle in the new Latium, that promised land of rich soils and vineyards that knows nothing of the McNugget or the Bacon Double Bypass or the drive-thru.

But then again when you look at those you’ve entrusted the project of civilization to, it’s never easy to be sanguine, is it?

Nevertheless, when you find people who know where they are and who know that the place has a past worthy of affection, you will also find in them an abiding sagacity concerning the future. Such people, generally unschooled in the hollow claims of politicians and advertisers, will frequently express that sagacity by not expressing it at all, which is only to say that they have no need to yammer on and on about “the future.” They understand that the unending but joyous task of securing a future requires of them not an obsession with its likely gizmos but the willing and sturdy shoulders of communal memory on which to carry its abiding hopes out of the present ruins.

That is to say, among such people you will find the local customs and the familial recipes, the barbecue pits and the game-day traditions and the festive holiday tableware, reminding everyone that each of us was made for better fare than Jumbo Cheese Doodles and the disenchanted mystery box of calories abandoned on the stoop by Door Dash. It is a great comfort to know that the various and repellent enterprises of frenetic modernity, poised to convert the gross laziness of the many into the gaudy lucre of the few, find no purchase among such as these.

A good image of what I’m gesturing toward is that spacious back yard on Easter, year after year, and the spit whereon the paschal lamb turns, around it men and women in whose memories the past isn’t ever dead, isn’t even past, and about them their children running and hollering with delight in the spring sunshine, not yet aware of what they stand to lose should they one day choose to leave.

There are many such images, as many images as there are places where good folk deep in this life perform the communal rites of place. Several of them are collected here in this issue of Local Culture, the first and I hope not the last devoted to food and drink.

But without the home kitchen and the family that eats from it there is no hope that these rituals of local life will survive. Those who care about all this might do well to be watchful; they might wish to defend the walls around the Ilium of home kitchen. The bizarre trend among young people to remain single, or to cohabitate and keep rescue dogs rather than have children, will not do for the civilized heirs of good custom. It won’t do for the inheritors of xenia and its lenient yoke of obligations. It won’t cut the mustard.

By singling out the home kitchen and the family that eats from it I don’t mean to say that there’s no place for the public house or local eatery or ethnic restaurant. Far from it. Such places are all a part of what the chattering classes ought to mean by “diversity.” Bardolph, Poins, Peto, Falstaff, Prince Hal—they all had their favorite houses of sack and the barmaids in them to banter with.

But when you choose to be fed and watered over feeding and watering yourself there is always a risk involved. For starters, not all bartenders are created equal. In my experience not three in a hundred can make a martini to suit even my pedestrian palate. Then there’s the risk that attends the food itself. When I took the best of gals to dine at an old standby to mark (rather than celebrate) her last birthday in the nifty fifties, that distinctive and never-dull decade of the quinquagenarians, I paid rather more than I now wish I had for a repast that turned out to be about as memorable as the musical careers of Ann Murray and David Hasselhoff combined. The lesson on offer, if we are attentive to it and willing to learn its moral, is this: in the main we should prefer to cook and dine at home, where culinary mistakes are ours humbly to endure, where comestible successes are ours modestly to celebrate, and where we live with the daily reminders of what freedom consists in: being equal to our needs and competent in the arts of making-do.

Plus we’re at home, where we belong.

But I say let there be gathering places nevertheless. I would not have the old Mayfair bar bulldozed, that sacred temple that back in the ’80s, golden age of mullets and big hair and wide lapels, was a place of peaceful coexistence for the blue-collar men who built the houses around it and the sturdy women who hit homers on the local softball diamonds near it. Longnecks weren’t the only shared interest there, nor was politics the only thing no one obsessed about. This watering hole was a place of familiarity and laughter and the crack of pool balls. And at the end of the bar was old B— W—, one of the local soakers, red-eyed and happy and amiable. He lived off the seventh green at a nearby golf course and was eager to offer a can of Olympia beer to anyone coming up the fairway, no matter the time of day. Thus did he ensure that he wasn’t drinking alone of a morning—not the best way to inhabit a place, I’ll warrant, but at least B— W— inhabited his place, all blurry and under-water though it must have seemed to his old and friendly eyes.

Let there be many variations on Dottie’s Diner punctuating what’s left of the landscape—Swedes, for example, a hole-in-the-wall breakfast joint in a little town called Sunfish not too terribly far from where I write this. Who couldn’t be fond of its aversion to the possessive apostrophe? Or who could grudge the price of a lunch to that distinctive west Illinois establishment, now a casualty of a downtown improvement project, that managed two charming grammatical impertinences on one sign: “Soup and Sandwiches at It’s Finest”? How is that not preferable to a Holstein Friesian on an interstate billboard telling me to “Eat Mor Chikin”? I say long live King’s Place and its baseball-themed burgers! And may East Lansing’s revered Peanut Barrel outlive me and mine, tous aionas ton aionon, as the Greeks around that paschal lamb are fond of saying.

I live outside a small-ish town that, notwithstanding its size (fewer than 4,000 residents), has several distinctive and locally owned restaurants, one of which in particular I have developed an affection for. Now of course it has its regrettable features, such as the odd over-the-top cocktail you invariably see in places that covet the anti-Applebee’s and anti-Olive Garden dollar—cocktails apparently intended to assist ex-sorority girls in bringing back their hour of splendor in the grass. But that covetousness is a low-level offense in the pageant of bibulous and gustatory sins, and so I don’t begrudge the nostalgic patron her “Lavender Martini,” even though, as the ingredients plainly show, it is not a martini in any sense: its base spirit is “Absolut Vanilia” profaned by lemon juice and lavender syrup.

(What I mean to say is that the word “martini” should not be used to denote a cocktail that lacks gin and the merest suggestion of vermouth, no matter the shape of the glass. Nor should “Vanilia” be in any localist’s vocabulary.)

But when on occasion I leave those two sons on whose shoulders I have placed so much hope—and there is some reason to hope, since they both happen to be built like Aeneas, if not possessed of his piety—when, as I was saying, I leave them to trash the home kitchen in their pursuit of an inscrutable preferred “caloric intake” of steamed rice and about six pounds of unadorned ground beef, wolfed down without regard for flavor, texture, or appearance, specks of half-masticated starch and protein airborne during their endless chatter about weight-lifting, usually transacted without regard for non-deaf creatures in the township and beyond; and when I close the passenger-side door of my ratty old car on that best of companions, sainted mother of these incipient (we hope) humans; and when in the sudden silence afforded us by the mechanical Jacobin I drive her away from the clamor and chaos, pointing my front bumper to the south of our little acreage populated by lambs, hens, and pigs both animal and human; when I motor toward this local and locally owned eatery and then in short order arrive—when in the fullness of time all of this comes to pass, then in advance of the mussels in Cajun cream sauce or the excellent club sandwich, I usually avail myself of a local special: a Makers Mark Manhattan the garnish of which is not one of those satanic store-bought Maraschino cherries, which not even rot-gut bourbon should ever have congress with, but a very thick slab of bacon that has been soaking up maple syrup tapped from Michigan sugar maples. I wish the bartenders could get the ice right. I wish they could get the rocks glass right. But this is our thing, here in our place, even as the swinish boys who at this moment are turning our kitchen into a sty are nevertheless ours. (Or would that be “our’s”?) I make no special claims about bourbon bottles with red wax on them, but I love the oursness of the place and the cocktail and the possibility of seeing friends and acquaintances at other tables. It’s pretty to eat so.

Across from the Manhattan with its bacon garnish there is a breakfast joint that descends from late antiquity. The interior walls are adorned with crosscut and bale saws and awls and other equipment from the old sun-powered farm economy. Thirty-seven years ago—in our first rambunctious year of marriage, about eight years before we left home and 18 more after that before we found a way to return—I would walk to this joint from our small apartment that in its early life was not an apartment at all but the as-yet unconverted choir loft of the old Baptist church (since perversely relocated to the city limits), across from which a dull new Catholic church rose from the charming ruins of the old. (A nun lived below us newlyweds, and we could hear her yawn!) On my way to the small office where I tapped out stories about the city council and the school board for the local paper I would stop at this joint for coffee and “home toast,” and during that year I developed a prejudice that I have tried to pass on to my sons, who so far do not seem to care about my perfectly reasonable throw-away opinions, such as, “When you go to a breakfast joint, you have until 6:29 to get there, otherwise, you don’t go.”

Why this should be seems plain as sausage to me: After 6:30 men wearing white shirts and dress pants start trickling in. There’s an earlier brotherhood, I tell the boys, and it’s the only fraternity you ever want to be a part of. Before the joint’s poorly-hung door opens its members are already waiting outside in the morning darkness, anticipating a diurnal sight as lovely as the sunrise itself: an egg sunny-side up with a few specks of black pepper on it. (Such artistry!) And when the door finally does open you can be sure that it will shut clamorously behind you after you pass through it. This is a calculated defect of the place and of all places like it. The noise of the door is a signal that everyone already on the inside should turn and look at the slacker who obviously wasn’t man enough to get up on time. And as for the slacker: he should be prepared to take his ribbing.

I wouldn’t willfully cast scorn on “fine dining,” which I like as much as the next bloke, but you can’t order a croissant or muesli at my old haunt, and if you ask for an omelet with pesto you should be prepared to pound the pavement. The streets nearby bear the names “Elm” and “Maple” and “Oak”; their cross-streets are “River Drive” and “Church,” and “Main.” It stands to reason that any breakfast joint that doesn’t open in the dark, even in high summer, is a joint made for another kind of creature altogether. The open-24-hours national chain isn’t even part of the discussion. If the men inside aren’t carrying pocket knives, I tell my sons, it’s no place for you.

Back in the day people smoked in the breakfast joint—it was one of those places, like a baseball stadium or a philosophy department, where you could count on smelling the pleasing aroma of tobacco. The early patrons were mostly men. The only woman in the joint was the waitress, and she was an excellent sport. It was a place of denim and flannel shirts and steel-toed boots and men who knew something about the best part of the day and a woman who could take a joke and dish a better one out.

And there it stands to this day, across the street from the slab of maple-soaked bacon. There is one difference: the daily special is no longer $1.49. Inflation has seen to that.

How will the succession fare? It’s difficult to tell. I think the boys have inherited my disdain for newspapers, and they have an appetite for good food so long as there’s someone nearby patient enough to prepare it. But my love of breakfast joints and my rules concerning them have so far failed of their effect: by the regimen of powdered protein drinks in the “morning,” which is nearly evening according to my watch, each boy aspires by unnatural means to become a dutiful Aeneas. It might take an ill-hung door and some well-timed trash talk to change this.

Nevertheless, I have hope for the household gods and the shoulders that will carry them. Those trapezius muscles were born of a good woman, a mother non pareil. Not altogether poorly will the succession fare.

* * *

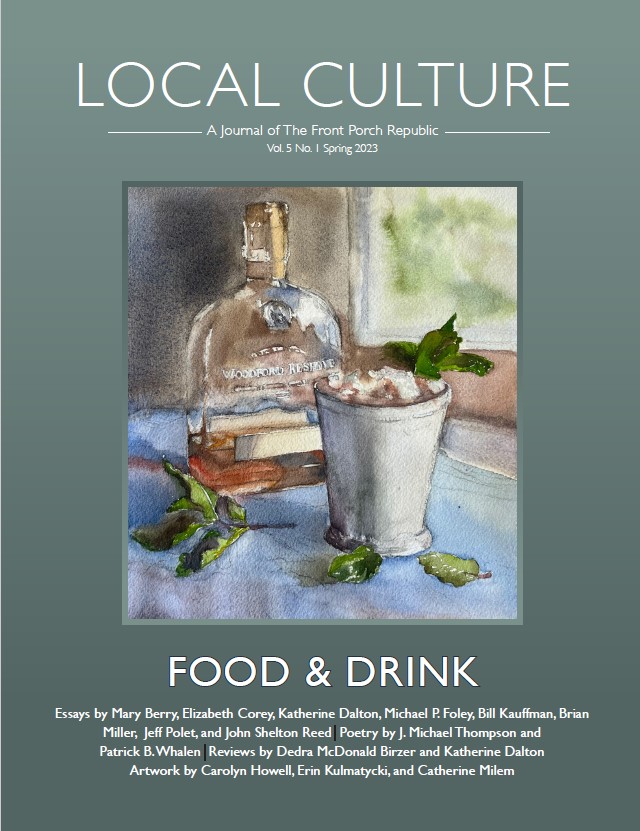

I am pleased to include in this issue the work of three talented young artists, all of them students of mine at Hillsdale College: Carolyn Howell from Miesville, Minnesota, Erin Kulmatycki from Perrysburg, Ohio, and Catherine Milem from Owensboro, Kentucky. I am especially grateful to them for agreeing to work, like the rest of us, for free. If anyone wishes to make a handsome donation to LC, I will divide it three ways and pass it along to these splendid and deserving young women.

— JP