Berliners love the Mozartsaal cinema. Its Art Nouveau style and glittering chandeliers remind audiences of grand old concert hall days. The First Massive Theater for Select Audiences, posters proclaim, and tonight, Friday, a packed house believes the hype. Lights dim for the 7 p.m. show. A drum roll, a black screen, “Carl Laemmle Presents . . .”

Then the catcalls begin. “Disgraceful!” hoarse voices yell. “An insult!” Soon house lights come up. Stink bombs fall from the balcony. Sneeze powder. And mice. Windows are smashed and fights break out.

Joseph Goebbels is screaming from the upper level for his storm troopers to shut down the picture. People flee the auditorium. Adding insult to injury, National Socialist demonstrators demand refunds for the three hundred tickets they had bought earlier that day—about one third of the theater’s seats. “The cinema was a madhouse in ten minutes,” Goebbels gloats in his diary that night. “They cancelled the first screening and the second. We won.”

It’s December 5, 1930. For six more days systematically choreographed assaults on movie houses continue across Germany. Nazis organize a protest march of sixty thousand people, most bused in from outside Berlin, including a large number that are paid to participate. The scheme works. On December 11 the German Board of Censors bans the film.

It doesn’t stop there. When this same picture premieres in Vienna’s Apollo Theater on January 3 1931, National Socialists marshal some two thousand demonstrators in protest. Mayor Karl Seitz will not be cowed. He deploys an equal number of police officers. But pressure has been building since 1929, when the movie’s source novel was banned by minister of military affairs Carl Vaugoin. Christian-Socialists pushed a resolution in December 1930 to prohibit the book’s Hollywood adaptation from appearing in federal provinces. Finally the minister of interior gives in and bans the film throughout Austria in what the Manchester Guardian calls “a capitulation before an organized mob . . . for a German crowd only has to make a great deal of noise and get any film, play, book or picture suppressed.”

The movie, All Quiet on the Western Front, does not play across Germany or Austria in 1930. Nazis exploit the premier of one of the world’s most popular films—winner of two Academy Awards for best director and best picture—to demonstrate that a minority can successfully assert its will over the majority. Goebbels’s campaign is a test case in how street terror can be used to destroy democracy with its own civil liberties: free speech and public protest. He observes that after Germany’s humiliating defeat in the Great War, inflation is rampant and people feel bitter about the imposed peace. He capitalizes on these emotions with cries of a return to morality and national greatness. With his victory over All Quiet on the Western Front, Goebbels writes, he controls Germany’s memory of World War One: “The National Socialist street now dictates the actions of the government.”

When the film is re-released in Berlin a year later, no one cares. The Nazi damage has been done. But the Great War’s impact remains.

World War One sees seventy million people called to arms from 1914 to 1918. Nine million die on the battlefield, two million of them German. Another twelve million return to Germany disabled or psychologically scarred or both. All Quiet on the Western Front presents these unsettling realities from a soldier’s point of view. Anton Kaes (University of California) says this kind of shell-shock cinema presents “experiences of loss and grief, experiences that resonate against a background of shared wartime memory.” Yet such deep-seated trauma remains taboo in post-war Germany. Silence about their surrender and its emotional cost has disastrous consequences for the nation’s first democracy, the Weimar Republic. “Unspoken and concealed, implied and latent, repressed and disavowed,” concludes Kaes, “the experience of trauma became Weimar’s historical unconscious.”

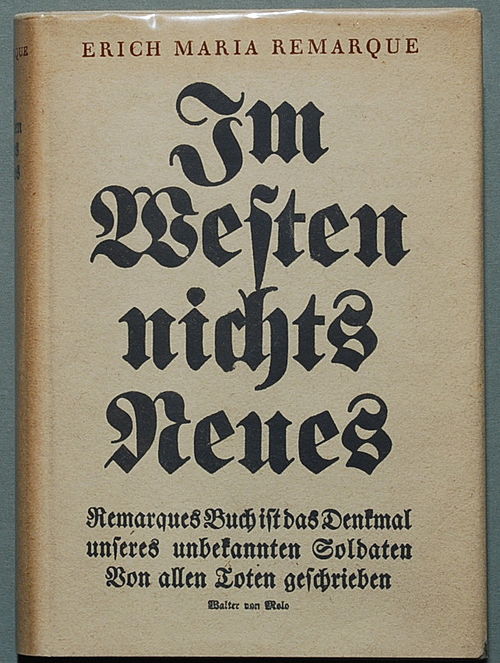

The film is closely based on Erich Maria Remarque’s global bestseller All Quiet on the Western Front (Im Westen nichts Neues). Producer Carl Laemmle with Universal Studios is eager to see it brought to the screen. His son travels to Germany to seal the deal. There Carl Jr is struck by the author’s good looks and star appeal. “He was very elegant,” writes Remarque’s friend of many years Marta Feuchtwanger. “He was very much an homme à femmes: the ladies liked him; he liked the ladies.”

Laemmle Sr asks Remarque to play the film’s lead character. The author declines. His casting surely would add fuel to the Nazi fire. But his novel’s intent remains intact. The film’s director, Lewis Milestone, is known for a commitment to source material: “I’ve tried not so much to express a philosophy as to restate in filmic terms my agreement with whatever the author of a story I like is trying to say.” Laemmle deliberately has Milestone begin filming on Armistice Day, 1929. It is the first major “talkie” about the war. Sound brings the battles to life, writes film historian Andrew Kelly (University of the West of England), with a violence that can be seen, heard, and almost viscerally felt.

All Quiet on the Western Front is released in April 1930 and is a worldwide box-office hit. Past British prime minister Lloyd George praises it as “the most outstanding war film I have ever seen.” Film critic Sidney Carroll, who served with the 2nd Light Horse Regiment at Gallipoli, writes in the Sunday Times, “It brought the war back to me as nothing has ever done before since 1918.” Nazi detractors insist that both film and book are filled with anti-German sentiment. They are not. “My work is not political, not pacifist or militaristic in intent, but merely human,” Remarque explains. “I simply hope to rouse understanding of a generation that above all others must make its arduous way back from four years of death, struggle, and horror.”

“Memories are like light shows, they deceive us,” Remarque tells an interviewer in 1963. “Harsh and cruel memories don’t remain, only the endurable ones.” His memories turn cold at an early age. Remarque is only three when his five-year-old brother Theodor Arthur dies. He barely remembers the event but acknowledges that this first brush with death informs everything that comes after.

He is born Erich Paul Remark to French émigré parents at 8 p.m., June 22, 1898, in the provincial maternity hospital of Osnabrück. In November of 1916, at age eighteen, he is conscripted into the German army. The following year, on June 12, 1917, Private Remark is transferred to Flanders during some of the most brutal fighting of the war. On July 31 he is wounded by shrapnel in the neck, right arm, and left knee. He is evacuated and sent to hospital in Duisburg.

A little over a month later, his mother Maria dies of cancer on September 9, 1917. Then his beloved mentor and friend, artist Fritz Hörstemeier, dies on March 6, 1918. This dual loss combines with his memory of mass deaths at the front to cause a deep emotional crisis in the young man, according to biographer Wilhelm von Sternburg: “Death has entered Remarque’s life and it will never again leave his thoughts.”

Remarque writes that “the pain still burns, the wound still bleeds” when he thinks of his mother and Hörstemeier. This is coupled with regret over time lost. To a war comrade he pens a letter from hospital that is as telling for its laconic tone as its underlying pain: “Pardon my long silence. My mother died while I’ve been away on vacation here and I haven’t thought about writing.”

He reveals a deeper grief in his private thoughts. “I haven’t seen you but five days total in the last two years, Fritz,” he writes to his dead mentor in a diary entry. “And the pain of my mother’s death weighs heavy on me.” By all accounts the young man’s mother was a lively, friendly person. His next action speaks eloquently of his sorrow. In 1920 he formally changes his name from Erich Paul Remark to Erich Maria Remarque, honoring his mother’s name and French origins in a way that will stay with him for the rest of his life.

Remarque remains in hospital until October 31, 1918, when he is transferred to the 78th infantry reserve regiment in Osnabrück. A week later the war is over.

The twenty-year-old feels listless, confused. He wanders from job to job: sports journalist, poet, teacher, opera and theater critic, tombstone salesman, church organist, a race car driver. It is as an ad copywriter that he first starts signing his name Erich Maria Remarque.

He spends a few weeks strolling through Osnabrück in a lieutenant’s uniform with unearned medals, including the Iron Cross. He carries a riding crop and walks a shepherd dog named Wolf. One reason is purely pragmatic: returning officers are treated well by the public, which might include free beer or even a meal. Remarque also observes, as he tells a friend, that in society appearances often matter more than reality: “If you hope to get ahead in life, always pay attention to your clothes.” It’s all something of a lark for him. At the time he has a teaching position. The school board insists he stop this nonsense, which he does, but the action is indicative of profound distress. Remarque’s mother and mentor are dead, he is wounded, and he is traumatized.

Returning veterans often face behavioral problems and feelings of remoteness from family and friends, write sociologists Pamela Moss and Michael Prince with the University of Victoria. They observe that discharged soldiers confront employment challenges and prolonged unemployment: “The affective distance between their traumatized self and their previous self produces intense anguish, grief, and despair.” Remarque is no different. Moss and Prince quote him in the epigraph to their essay, “Soldiering On.”

I know this much: everything that sinks into us like a stone now during the war will resurface when the war is over, and that will mark the beginning of our true life-and-death struggle.

Remarque expresses a sense of alienation from people who weren’t at the front with him and cannot grasp the grotesque nature of combat. “His inability to relate to his former life deepens his solitude,” notes researcher Arpita Singh. The war is over but soldiers cannot flip a switch and rejoin society. “You can’t put everything back, forget everything, with a single command,” Remarque says. His pain seems to have no end.

Bessel van der Kolk, professor of psychiatry at Boston University School of Medicine, suggests that we are better equipped to endure pain that we know is finite. The opposite is also true: suffering that seems endless can become intolerable, overwhelming, unbelievable, and unbearable: “Terrible grief is typically accompanied by the sense that this wretched state will last forever.” Lawrence Langer (Simmons University) agrees. “Life goes on, but in two temporal directions at once, the future unable to escape the grip of a memory laden with grief.”

This is the experience of another soldier who serves in the Great War. British Army Colonel T. E. Lawrence, known as “Lawrence of Arabia,” advises Bedouin forces revolting against the Ottoman empire from 1916-1918. “The body was too coarse to feel the utmost of our sorrows,” he writes. “We learned that there were pangs too sharp, griefs too deep . . . for our finite selves to register.”

Remarque feels distant from nearly everyone he meets, family and strangers alike. “Only those who did not return, who can no longer speak, may fully grasp what war really is,” he says. “The dying are alone, always alone, completely alone.”

Memory plagues Remarque. Within weeks of his return, he notices that public memory, along with his own, is slowly embracing the proverbial rose tint of nostalgia. “You see, the war—those who escaped, those who survived—is gradually, slowly but inevitably, remembered as something that it was not. Now it is like some great adventure and not its reality: you go to war to die.”

Remarque decides to write about his experience. Two earlier novels were dismal affairs that would make him wince in later years. But now in 1927, over the course of a few months (perhaps as quickly as five weeks), he fills each page with pain and sorrow. “Like a Pandora’s box of human struggles,” says Robert Neimeyer, director of the Portland Institute for Loss and Transition, “the grieving heart pours out a vast and varied torrent of troubles.” Remarque pens a tale of narrative precision steeped in relentless grief.

The resulting novel, All Quiet on the Western Front, is rejected by some of Germany’s leading publishers. By 1928 the plethora of war literature has reached its peak in the Weimar Republic. Editors fear reader enthusiasm is waning. Prestigious S. Fisher tersely dismisses the book out of hand. Remarque receives more callous rejections before Ullstein, an established liberal German Jewish house, serializes the novel between November 10 and December 9 1928 in Voss’s News (Vossische Zeitung).

All Quiet on the Western Front is an instant success, hailed as a modern classic by the Berlin literary establishment. Ullstein quickly publishes it in book form on January 29, 1929. Within six months the volume sells over half a million domestic copies—the first German title to do so in so short a time. The novel is then translated into twenty-two languages and sells 2.5 million copies in its first eighteen months. By 1930 it has sold twenty million copies. Philosopher Walter Benjamin isn’t surprised. “Wasn’t it clear at the end of the war that men returned from the trenches in silence? Not richer—but poorer—in experiences that could possibly be explained to others. What flowed forth ten years later in the flood of war books was anything but the kind of experiences that could be shared in conversation.”

Mary O’Neill with De Montfort University suggests that creative expressions such as All Quiet on the Western Front offer permanence and understanding in a society that too often denies sorrow: “When a culture no longer provides adequate forms of mourning, these works can act as a means of engaging with bereavement, disenfranchised grief and ambiguous loss.” Brian Murdoch (University of Stirling) suggests that the novel’s success and longevity are due in part to its double historical context: the setting of the Great War and those tortuous years in the Weimar Republic before Adolf Hitler assumed power.

Remarque does not intend his novel to be autobiographical. “It’s simply a collection of stories, really, that my friends and I shared over drinks as we relived the war.” But the book contains truths that transcend fact. “It is not artful construction of fancy,” writes T. S. Matthews with The New Republic, “but the sincere record of a man’s suffering.”

All Quiet on the Western Front avoids unnecessary flourishes or purple prose. Later, Remarque returns to the Great War in his 1936 novel Three Comrades (Drei Kameraden). Through his main character, Robert Lohkamp, he speaks calmly and plainly of mourning and love:

I felt a dull grief that had sunk in me like a stone, awash again and again with wild hope, changing and strangely blending, one becoming the other: grief, hope, the wind, the evening . . . yes, for a moment I had the uncanny sense that in a real and profound way this is life and maybe even happiness: love with so much sorrow, dread, and silent knowledge.

Fame earns Remarque an interesting place in history. Goebbels, now Minister for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, condemns All Quiet on the Western Front as “a literary betrayal of soldiers of the world war.” He pushes for other authors to write nationalistic novels throughout 1929-1930 to distract from Remarque’s popularity and Germany’s slide into economic depression. Then on May 10, 1933, a little over three months after Hitler is appointed chancellor, All Quiet on the Western Front joins works by Albert Einstein, Helen Keller, F. Scott Fitzgerald, H. G. Wells, Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Victor Hugo, Sigmund Freud, Thomas Mann, Heinrich Heine, Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Leo Tolstoy, and others in the infamous book burning before Berlin’s opera house. Erich Kästner watches from the crowd as Nazis toss his children’s mystery novel Emil and the Detectives into the flames.

Twenty thousand books are burned that day in Berlin and university towns across Germany. Fire marks the start of a Nazi campaign to purify national culture of anything Goebbels deems “un-German,” “an enemy of the German spirit,” or “degenerate” (entartet). But modern memory sees things differently.

Walking through Bebelplatz square in the central Mitte district of Berlin, you may come across a transparent plate set among cobbles. Under the glass, far below, are rows of bare, white, empty bookshelves—enough to accommodate twenty thousand volumes. Mischa Ullman created this monument in 1995, calling it “Bibliotek” or “Library.” For his commemorative plaque, the Israeli sculptor chose words from Heine’s 1821 play, Almansor, in which a character witnesses the burning of the Qur’an and exclaims: “This is but a prelude: where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people too.”

Remarque leaves his homeland in 1932. “I am no more German,” he says, “for I do not think German or feel German or talk German.” This distancing is part and parcel of many soldiers’ post-war experiences. And it’s not permanent. On May 9, 1957, he writes to his childhood friend and fellow veteran Hanns-Gerd Rabe: “Osnabrück is as close to my heart as it is to yours.” He adds that they were both born and reared there. Their old hometown companions may call him a modern child of the world, but his new friends know him as the Osnabrücker. “We can never deny anything. One look at my books and you can see that each has a piece of Osnabrück.”

Over the years Remarque’s love life is filled with joys and disappointments. In 1925 he marries actress Ilse Jutta Zombona. They divorce in 1930, only to remarry in 1938, more or less in name only, to help Ilse escape Nazi Germany. That same year Remarque meets Marlene Dietrich in Paris. They have an open affair for many years after they both move to the United States in 1939. Despite this and many other romantic assignations, his writing never suffers. “You have to work,” he tells himself. “Build your world, shape yourself, it’s important.” He defines his life credo with three words: Independence, Tolerance, Humor.

But Nazi hatred for Remarque doesn’t abate. They continuously repeat an absurd lie that his birth name was not Remark at all, but Kramer, a Jewish surname spelled backwards. After the author leaves Germany, they lie in wait to arrest his younger sister, Elfriede Scholz, a Dresden dressmaker. They have their chance in 1943 when Elfriede’s landlady and a customer denounce her to the Gestapo for making critical remarks about the government.

She is arrested on August 18 and jailed in the police station along Schießgasse in Dresden. Later she is transferred to Moabit Lehrter Strasse Prison in Berlin, where she is indicted by the President of the People’s Court Roland Freisler on October 29 for “publicly undermining the military might of the German people and thereby aiding and abetting the enemy.” Elfriede is imprisoned in a woman’s facility on Barnimstraße. Finally she is transferred to Berlin-Plötzensee prison on November 25, 1943 to await execution at five o’clock that evening.

Elfriede thinks of her brother living a life of luxury and renown. She’s not bitter, but as she waits for death, watching spiders crawl along the damp walls of her cell, she knows this came about because of his books. Prison chaplain Peter Buchholz visits to offer comfort and confession. His act of compassion reminds her there will be no escape. Alone now, she sees leaves falling outside her window. Autumn, she thinks, recalling Rainer Maria Rilke’s poem by that name which she had memorized years before:

Leaves fall, fall as from far away,

as from gardens withering above;

fall even as they resist falling.

And in the night, this heavy

earth falls into solitude.

We all fall. This hand, too.

Look: others fall, they all fall.

Yet One with infinite gentleness

holds this falling in His hands.

Perhaps our souls continue on, she muses. Maybe there’s hope, if not in this life, then the next. A prison guards enters her cell. “No execution today. The officiating officer has been delayed.” Shocked, Elfriede asks for how long? “No one can tell.” But her reprieve is short-lived. On December 16, 1943 Elfriede is led to the guillotine outside Berlin-Plötzensee prison. “Your brother managed to escape us,” they tell her. “You, on the other hand, will not.”

The news of his sister’s death is a heavy blow. Remarque had grown distant from his family over the years, but the thought that Elfriede was killed because of him is too much. He suffers a breakdown and falls into deep depression.

Yet in time Elfriede’s memory spurs him to action. The year of her death, 1943, Remarque becomes a naturalized United States citizen. In 1957 he and Ilse finally dissolve their marriage of convenience. The next year he weds Paulette Goddard.

Then, in 1963, the author whose work was once banned in Germany returns as a guest on Berlin’s SFB television. Remarque astonishes viewers with a revelation about his most famous book. His experiences inform much of All Quiet on the Western Front, he says, but one scene happened exactly as he wrote it.

In the novel, Paul Bäumer takes cover in a foxhole when French soldier Gérard Duval falls into the mud beside him. Bäumer knifes Duval and watches for hours as the man gasps for breath. Duval dies at three o’clock that afternoon. Bäumer finds the Frenchman’s wallet, his letters, and family photos. He realizes that Duval is not a demon, merely a man, as he is a man, against whom he bears no grudge. “Forgive me, my friend,” he cries to the dead man. “We always learn too late. Why don’t they tell us that you’re just like us, poor devils missed by mothers, who fear death as we do: the same dying, the same agony. Forgive me, my friend. How could you be my enemy?” In a paroxysm of regret, Bäumer swears to write the man’s wife. “She will not suffer, I’ll help her, and your parents, and your child—!”

Berlin’s television audience is mesmerized. Speaking quietly, as much to himself as the interviewer, Remarque continues: “I didn’t keep my promise to meet his wife. To appear before her, the man who killed her husband, would be cruel. It could only hurt her.”

Perhaps he’s right. Perhaps not. But it’s his decision to make, his life, his memory. “We cannot change the past,” says psychologist Karen Reivich (University of Pennsylvania). “All we can do is show up for the present and work toward the future.” Remarque does just that. He shows us how in his 1952 novel, Spark of Life (Der Funke Leben):

But he was also suddenly aware that the responsibility placed on him by the dead would not be an unbearable burden as long as it included this clear, strong sense of life. It would carry him and give him strength twice over: not to forget, nor to perish from memory.

__________

All translations from the German are by David Bannon.

Image via Wikimedia

2 comments

Kevin Marsden

Excellent post. I greatly admire All Quiet on the Western Front (and think it should be required reading for anyone running for political office), so it was nice to learn more about Remarque and how the novel came about.

David Bannon

Thank you, Kevin.

Comments are closed.