For those who value limits and place, people and communities, tradition and things divine, not only are there few viable options within the higher education landscape today, but the very educational institutions themselves actively work against the health of communities and defy the realities of limits and locality. It is even more so for Christians, for whom love of one’s neighbor and place is inseparable from their faith. The Lord himself lived among us, in a particular place, with particular people, loving them, walking among them, and healing them. In doing so, he healed the whole world. Love of neighbor and place must therefore be central to each Christian’s life. To be formed in institutions that neglect limits, place, and community, formed not only ideologically in the classroom but even more powerfully by the institution’s way of living, is not a small thing. The effects of such formation are even weightier for young adults. Higher education at such a young age sets—or resets—our loyalties, our hopes, and our loves.

It is clear enough that the large public universities are far from valuing limits, place, and people. Students there are known by their numbers: a number gets a book checked out at the library desk, gets you registered for classes, and gets you help at the IT department. Unknown by advisors, students are slot into a class schedule that fits the degree track—not who they are, and what they need. They move unknown through classes, past professors, and across the stage where “We are Proud of our Students” is expressed for the hundredth time, without the president or representatives quite being able to say what they would be particularly proud of in each of their students. The continual emphasis on global change, global solutions, and a global mindset makes clear that the vision for these universities is not a local one, but one that grasps hungrily at the entirety of the globe.

On the website of a major public university in Texas, one of the first lines on the front page advertises “Our Next Frontier” and proceeds to outline the next satellite campus the university is planning to develop on a ranch in West Texas where “the horizon’s wide and the opportunities even wider.” There is no mention of the city or the wider county in which the current university resides. No mention of the people native to its place. In fact, aside from seeing the name of the university and the address at the bottom of the front webpage, one would not know in what place this university was located at all. But such a pattern is not particular to this university, and its example is not exceptional. Universities across the nation hold to the same pattern. There is an undergirding belief that what is out there is better than what is here. What is here is debasing, while what is out there is bright, if only we can move fast enough, and have the power to bulldoze any obstacles in our way. Just recently, an ad for a university in Arizona urged students to “Apply today to make tomorrow great.” Even this present moment is given up to tomorrow, a brighter future. The statement quietly assumes today is not great. This time and this place are not enough. These people are not enough. And perhaps something more is needed in this moment. But is applying to the university the panacea? Does the institution have the solution?

Elite private institutions are, most often, just smaller versions of these public institutions. Promises of high-quality education, bustling campus life, careers beyond college, and accolades of prestige give a sense that these colleges are formative places. And perhaps they once, in some measure, were. But today they often wrap the assumptions and aspirations found at public institutions in a more glittering package. Surely in some, the education, or at least the comforts and mode of living, are of higher quality. But just because students are in a more bedecked boat than those who attend public universities does not mean they are not floating down the same river. Even the reform-minded, “new” institutions—places like the University of Austin—aren’t challenging the deracinating assumptions that shape higher education. These institutions sell the same value of beyond here. They look to impact the world, even for good, yet forget their own place and its souls.

But what about the smaller Christian liberal arts colleges? The situation with these colleges is a bit more complex, and the difficulty with them varies from college to college. Some Christian liberal arts colleges are simply so by name, and run on the same river as the public and private institutions. Some are very sincerely committed to a Christ-centered, virtuous formation of the individual. This time, though, forgetfulness of place and one’s people is excused by higher, loftier purposes—even “Christian purposes.” Changing the world for the glory of God allows one to forget one’s loyalty to home and the people who formed them and know them. The pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty forgets its higher purpose—love, a lived out love—lost in intellectual inquiries and lofty goals of helping mankind. While sincere, seeing formation of a virtuous person as an end in itself, without being attached to the flourishing of place, is abortive and rejects its own assertion of following the liberal arts, the arts that enable one to live generously.

The pursuit of truth, goodness, and beauty forgets its higher purpose—love, a lived out love—lost in intellectual inquiries and lofty goals of helping mankind.

The remaining options, then, for higher education are junior colleges and online education. The system of education at junior colleges takes after the same pattern as the public institutions, just with a generally poorer quality. So, although they are often a local option, they are not one in which a student could dependably expect a good education even by modern standards, which are low enough. Online education, which does allow students to remain in their local communities, actually guts out the most important part of local education: relationships with people and place. Strangely, although students may remain physically in their own places, online education takes their presence away from their community, or any community at all. A student’s mind and heart dwells in another world, their senses becoming mute and their bodies absent from the living world around them. Thus, being disembodied by nature, online education cannot offer a genuinely local education.

* * *

If we are going to be Christians, or any lover of place and people, we must, at least, begin to see and name how deeply the modern higher education industry subverts the very nature of embodied, placed, limited humans.

There has been creative work to reimagine secondary institutions in recent years, but higher education has resisted similar efforts. Maybe that is because it is considered out of reach of the “average” person. Only the specialists—those certified—can touch that space. Or perhaps the university has not been touched because it is so ingrained in our belief of “growing up” and “living the good life” that we are afraid to touch it. Or perhaps it is because the very people that are going there, the young ones, are no longer home, and we cannot quite see what is happening day by day enough to really be sure that the universities are, this time, as destructive as we suppose. But, for whatever reason, the deep issues of the university system today have resisted imaginative reforms, and the suffering that has ensued as a result is only deepening.

It seems that amidst this ongoing breakdown, the cry for help has sounded loud enough and we have begun to hear a response. Some responses are quiet, though, and can’t be documented in an article. And this brings us to a very important point in terms of ‘solving’ this higher-ed issue. In a world of Progress, calculable, documentable “solutions” are always for sale. But the Christian (and the majority of pagan and ancient cultures) believes that a man alone praying in the desert can send ripples of change throughout the entire universe. That solution can never be commodified or institutionalized.

With no way to measure prayer or quite express in material forms what comes from the soul into the world—as prayer, as a cup of water handed, as the sparkle of a soul bursting through into a smile—with no way to capture in numbers or even words this impact, there is no success in Progress’ books. But in other books such gestures constitute reality.

It is not that projects or things that are capturable in numbers are not worth anything. Certainly not. But the idea that this is all that matters, or what matters most—the thought that well yes, having tea with your neighbor is good and all, but really, we need to get to work at some point and solve this mess is quite a different thing. It is these thoughts that have allowed us to degrade in our culture the work of care, such as the work of a mother, in favor of the work of ‘progress:’ celebrities, businessmen, politicians.

The humble appearance of genuine transformation should discipline any discussion of “solving” higher education (or any current cultural issue). The reality can also remind us that the university system is a living expression and perpetrator of something much more all-encompassing. It is the living out of a Story. The Story of the individual, of freedom as breaking limits, of success as documented, credentialed, degrees, careers, and institutions. This Story is anti-nature, anti-human, anti-Christian. And we tell it by living it. No tweak in curriculum will fix this. We must enact a different Story.

So this is the first thing to note: The “solution” to the higher-ed problem might not be capturable in a plan and expounded in an article. It is too deep beyond the reach of these things. Words can gesture toward it, but they cannot capture and quantify it. Educating people to work and keep the communities to which they belong requires a conversion of the heart, it requires us to live in a different Story. That is the first thing I would like to say.

But some things can be expressed in an article and I would like to make mention of one because it is of great importance and is something quite encouraging. Over the last few years, people have begun forming small, local colleges that offer accredited degrees and trade programs, depending on what is needed and can be offered in the community they spring up in. The accreditation comes through university partnerships established by Christian Halls International, which was founded to support these small organizations. The hope of each hall is the same: to give the members a local group that offers deep, whole-person formation in the place they live. In short, an education. There are halls that have begun all over the US. Some are very small and just starting. Others are more established. Each one, though, is unique to its place and people. No one hall looks the same as another. And this is one of the most beautiful things about the halls. They shouldn’t look like Oxford halls—though they may be inspired by them. They are New Jersey halls. Texan halls. Kentucky halls. The mentors are professors, teachers, tradesmen, grandparents, businessmen in the community. Some halls have only a couple students, others may have many more.

The idea is not to mass produce local halls. That would be the same old Modern Story in another form. The ‘success’ of these halls will depend on local work. Local need. Local love. That’s it. There are no guarantees. It will be alive and dynamic.

Perhaps some of us will find our work to be done in such a space. If we are able and see a place for it, it is deeply needed. But building a perfect hall is not the goal. The goal is simply being more alive, being human, becoming who we were meant to be in loving and caring for our neighbors. And a hall could very much be a part of that. But if we find ourselves sacrificing the first things (those that often seem little and insignificant) in our lives to a Big Solution or Project, it will be vital to see that perhaps we have altogether missed the point once more.

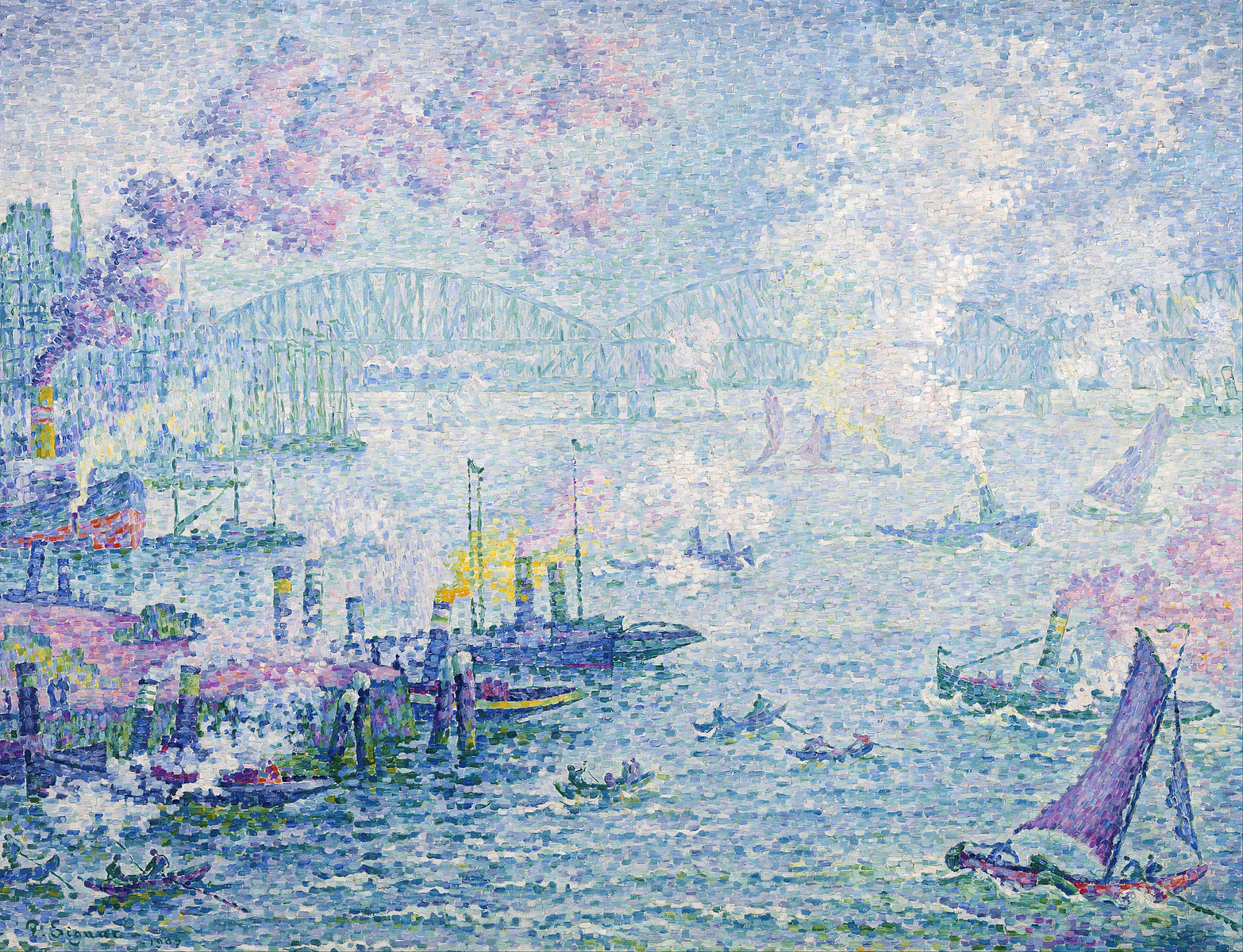

Image Credit: Paul Signac, “The Port of Rotterdam” (1907) via Wikimedia.