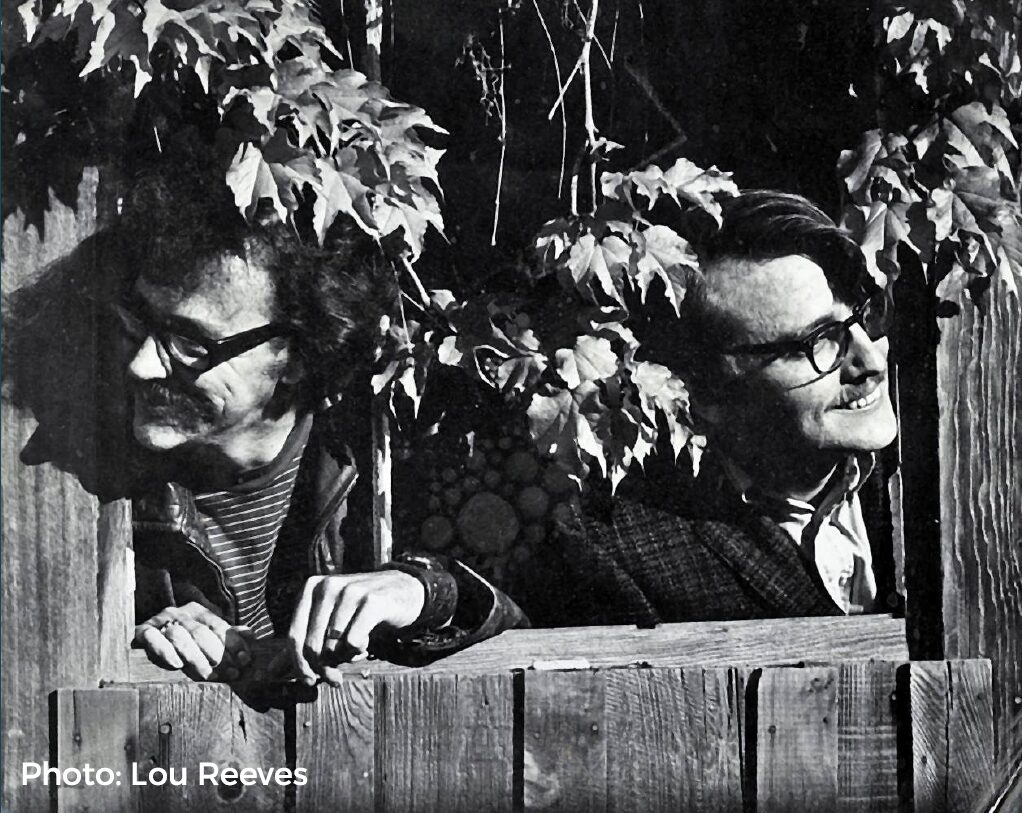

I cannot remember precisely when I first met Gurney Norman, who passed away this past Sunday, October 12, 2025. I do know it was while I was a graduate student in history at the University of Kentucky in Lexington. And I do recall that it was at a party at the home of one of my committee members, Kathi Kern. Though I was aware of and had met his wife Nyoka Hawkins, I did not know who Gurney was. I simply remember sitting in Kathi’s living room talking with this older man who asked questions about me (and my research interests) and who shared wonderful little stories about growing up in eastern Kentucky. His questions, though, are what stand out the most in my memory. Or more accurately his manner of asking the questions in a way that was uncommon for much of my grad school years. He asked and then genuinely listened—deeply and intently. Over the next year or so, I found myself talking with and being listened to by this kind-eyed man with memorable stories. It wasn’t until a few years later when I made a deep dive into the poetry and nonfiction of Wendell Berry and saw the name Gurney Norman constantly showing up that I all-too-slowly realized who I had sat across from and been in conversation with at those parties. And I realized I hadn’t stopped and genuinely listened enough to him.

A few years later, when Ed McClanahan, one of Gurney’s longtime friends, invited me into a recurring conversation and friendship throughout much of the last decade of his life, I made certain to learn from Gurney’s example. I set out to listen more deeply and intently. My conversation and friendship with Ed spurred an interest in the counterculture movement in Kentucky as seen in the writings of several of its most prominent writers, a group that included both Ed and Gurney. Hoping to learn more from them, I reached out to Gurney in preparation for my stint as a fellow in the Kentucky Historical Society (KHS) and asked if I could host a conversation with him and Ed. Before being willing to agree to such a public conversation, Gurney requested I call him for a talk. When the morning for our phone call came, I sat in the KHS parking lot for more than an hour listening as Gurney wove a web of connections between localism and regionalism, Kentucky mountains and rivers, Appalachian culture and counterculture. In the end, he enthusiastically encouraged me to continue my pursuits and offered to assist me in any way he could. Furthermore, he agreed to join Ed and I for what promised to be an exciting time of talking and listening. On June 12, 2019, then, the three of us sat in front of a packed room at West Sixth Brewing in Lexington for what we had dubbed the “Gurney & Ed Show.” As I asked a few questions and tried to get out of their way as quickly as possible, the community of writers, artists, scholars, and students gathered made it clear that more than a few other people wanted to listen, as well.

Though we shared time in Lexington and in the Patterson Office Tower on the university’s campus, Gurney was never officially my teacher. That said, as seen above in the ways he encouraged me to listen more intently, Gurney did provide some clear instruction, especially as I pored over his writings and documentaries to learn more about him, his influence, and his place in Appalachian literature and in bringing countercultural ideas to the Commonwealth of Kentucky. Thus, I gladly count myself one of Gurney’s students. Unlike most of his students, I don’t write fiction. I do, however, write stories. And I remember vividly the moment in 2019 when I read Gurney’s “Storied Ground,” in which he insisted that “Stories are meant to be told and retold, again and again, not just by the original tellers but by others in a family or community who have recognized them as living treasures to be cared for and handed on.” As a historian, then, I learned from Gurney that it is okay to be one of those who is telling and retelling a story.

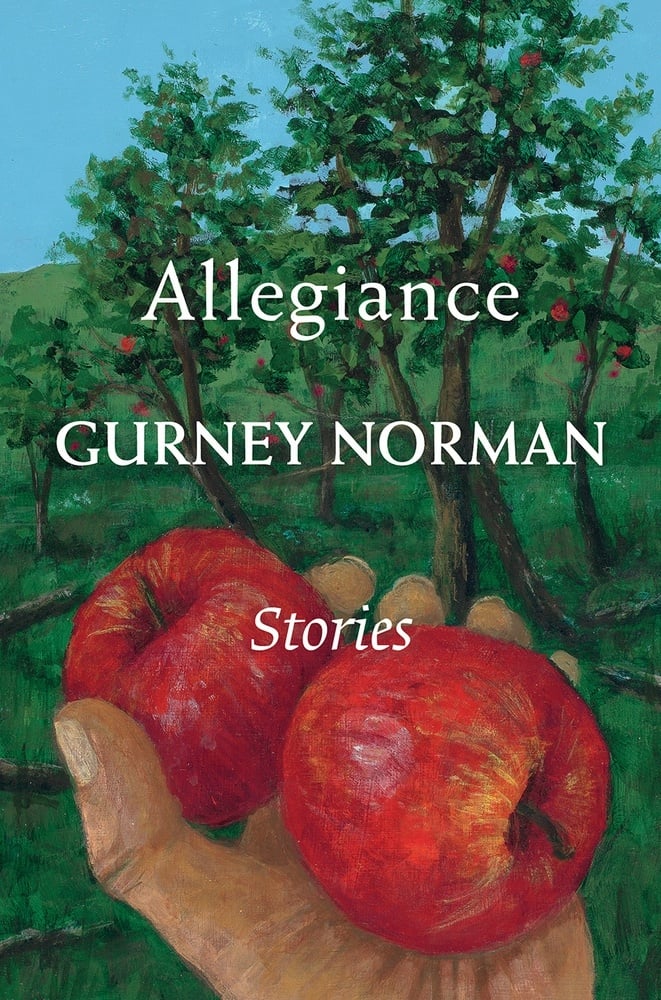

Sometimes that telling of the story means to stress more of the subjectivity of the story and less of its objectivity. Gurney reminded me of this truth near the end of his “stream-of-conscious piece” that closes out his short story collection, Allegiance. “Since we are in a confessional mood here,” he writes, “let’s face the fact that in the grand scheme of things subjectivity is as interesting and useful and important as objectivity what’s going on out there is equal to what’s going on in here and vice versa.” As I continue writing toward the end of my study of the counterculture in Kentucky as seen specifically in the ways in which Kentucky’s Fab Five of writers—Wendell Berry, James Baker Hall, Bobbie Ann Mason, Ed McClanahan, and Gurney Norman—address specific themes in their writings, these passage from Gurney’s “Shattered Jewel” remains a reminder that harvesting their fiction for insights into their lives is an appropriate way to get at both the subjectivity and the objectivity.

Gurney also taught me that as a historian, I need to remember not to take myself too seriously. Or at least not any more seriously than any other storyteller. All storytellers are important. I encountered this lesson in the epilogue of his wonderfully weird novel Divine Right’s Trip: A Novel of the Counterculture. In that chapter, which details the wedding of the protagonist D.R. Davenport and his bride Estelle, a whole host of the couple’s friends from California and Oregon arrive in Kentucky for the impending nuptials. One member of that somewhat motley crew was the Captain, “an utter freak in purple velvet and long mustache and a conductor’s hat too small for his shaggy head [who] held a tape recorder mic” as he interviewed everyone around him to start an archives for the couple (if you want to see Ed McClanahan in that description, well, you wouldn’t be wrong). When the Anaheim Flash hears of the Captain’s assignment, he nonchalantly replies “I can dig it.… Archives are the minestrone of history, and history is the spaghetti of cosmic time.” Admittedly, I don’t know that I rightly understand what that statement means, and I wish I had asked Gurney. But listening to him in the “Author’s Note” in Allegiance helps me somewhat. “I wanted to end this collection,” he writes, “with a stream-of-consciousness story because it returns us to that place which has not been ‘worded’ yet, a place of imagination and dream life and memory. The human mind is restless and curious. Anybody can feel that there is something beyond just what we know. And some of us want to know what that next things is, or what that further realm of thought is … we are venturing into the border regions of the psyche where human consciousness flows into cosmic consciousness.” Thus, as I remind myself that history, as a work of imagination and memory just beyond what we know, is the spaghetti of cosmic time, I realize that there is so much more to the story than the facts of history.

A final lesson Gurney taught was the significance of friendship. I first saw this in the relationship between Gurney and the writings of Wendell Berry, his friend of nearly seventy years. Gurney regularly shows up in Berry’s poetry and essays, such as his essay “My Conversation with Gurney Norman” and his poem “Grace.” Ed McClanahan regularly regaled me and the rest of our weekly salon crew with Gurney stories from their times in California, in Oregon, and in Kentucky. A few such instances can be found in classic McClana-style in his “The Day the Lampshades Breathed” and “Me and Gurney Goes Out on the Town.” Bobbie Ann Mason, the youngest of Kentucky’s Fab Five of writers, included Gurney in the dedication of her most recent novel Dear Ann. Since learning of his passing early this week, I have read the tributes of other friends of his. From his wife Nyoka to Johnny Lackey to Silas House to Crystal Wilkinson to Robert Gipe (to name only a few), they to a person remember with gratitude the man who valued them and honored them with his friendship. Re-reading his “Shattered Jewel” this morning, this passage near the end helped me understand a lesson Gurney taught us all about friendship. “Which approaches,” he writes in the stream-of-consciousness style he promised, “knowing there is a limit to your days inspires appreciation allegiance faithfulness to those and what you love all the people gone and around me still sweet family dear friends colleagues associates the days are sweeter as there are fewer of them. Society does not exist just for the people who are alive.”

When a young Wilgus Collier’s grandfather entrusts Wilgus (an analog for Gurney) with one hundred dollars to give his grandmother along with the news that he is leaving her with the intention of divorce, Wilgus struggles mightily with the weight not only of the task, but also of the news he must share. So the boy decides maybe he ought to leave, as well. By becoming a mystery to her, he thought he “might save her from the terrible thing he knew.” His decision to leave “would be tough on them all, but even so, even if they all were sad and lonely the rest of their lives, still they’d be lonely inside a web of love.” As Gurney’s family and friends wrestle with the loss of their friend, I hope they—or more accurately we—will lean into being lonely inside a web of love.

Some Suggested Reading (and Viewing)

Let me invite you to get entangled in this web of love that Gurney wove over the years by spending some time with a few of the many words he wrote and spoke. If you are so inclined (and really you ought to be), here is a list from which you might make your way into the world Gurney shared and narrated.

Divine Right’s Trip: A Novel of the Counterculture (1972): originally published serially in the Last Whole Earth Catalog in 1971, this novel follows its protagonist, D.R. Davenport, as he travels cross country in his 1963 VW microbus, christened “Urge” in true Merry Prankster fashion. With no clear place ahead him, D.R. finds himself drawn to his “place” in Kentucky, countering Thomas Wolfe’s claim about not going home again.

Kinfolks: The Wilgus Stories (1977): a masterful collection of ten short stories about life in Appalachia through the eyes of Wilgus Collier and his family. Silas House, poet laureate of Kentucky from 2023-2025, claims that “Kinfolks by Gurney Norman is to Appalachia what Dubliners by James Joyce is to Ireland.” Three of these stories were also made into short films, known as “The Wilgus Stories,” which can be found on Youtube .

Ancient Creek: A Folktale (2012): a story following the hero Jack as he leads a revolution against an industrial colonizing empire. Listening to the 1975 recording of Gurney reading this at Appalshop, a nonprofit arts and education center in Whitesburg, Kentucky, is also a delight.

Allegiance: Stories (2021): another collection of mostly Wilgus stories, these autobiographical stories reveal more about Gurney’s and Wilgus’s lived experiences in Appalachia, documenting the disintegration, the determination, and the resilience of the region and her people.

“The Kentucky River” (1987): A Kentucky Educational Television (KET) documentary written and presented by Gurney in which he treats the role of the Kentucky River in the settlement and development of the state. This documentary can be found in four parts on Youtube, as well.