“Be sober, be vigilant; because your adversary the devil, as a roaring lion, walketh about, seeking whom he may devour.”

— 1 Peter 5:8

I lost count of how many times someone quoted Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance when I mention I ride. Usually they grin, as if Pirsig’s book finished the conversation on motorcycles, philosophy, and the open road. I’ve rolled my eyes more than once. The clichés arrive fast: wind therapy, two wheels one soul, freedom on the highway. T-shirts and bumper stickers stamped them flat until they lost their sting. And yet, clichés keep circling back because they hold truth.

I never climbed onto a bike for slogans. I turned to riding to mend myself after years as a child protection investigator—one of the hardest tours I survived. Day after day, I sat in kitchens and courtrooms where the worst stories surfaced, and children endured what no one should. The walls of my community felt thinner after that job, the air darker, as if the shadows in those files crept into every hallway and waiting room. I carried those stories home in my bones.

What drew me toward motorcycles wasn’t a craving for speed. It was a biker group in my own community—ordinary people, patched and loud, who volunteered to stand with abused children so their voices could reach a courtroom. They gathered around kids whose families had failed them, shielding them with the simplest strength: presence. Their machines weren’t symbols; they were guardians. They didn’t erase wounds, but they showed me how to ride through them. The bike wasn’t just waiting in the garage. It walked me back to myself.

The rides I know best don’t stretch across the country or end in cinematic revelations. Outside of Rockford, IL, they snake through Shirland and Rockton, bend with the Sugar River, and run alongside the Rock River when it widens under the sun. These aren’t roads people put on postcards. They belong to farmers, truckers, kids heading to football games, and a few of us on two wheels who slip between it all.

Take Shirland, for instance, where Stumpy stands—a seven-foot tree stump a farmer keeps dressing for the seasons. One week it wears green beads and a shamrock hat for St. Patrick’s Day, another week a Santa suit. It doesn’t mean anything profound, but you notice it every time. Local riders mark their bearings by it. Some places offer monuments or scenic lookouts. We get Stumpy. Maybe that’s better: a reminder that survival sometimes just means standing where you’ve been planted, even if you’ve lost everything above the roots.

Out here the road doesn’t speak theory—it breathes. It hums with fields, leans with old farmhouses, flashes with hawks cutting sky. The road doesn’t hand out philosophy. It throws weather, pavement, wind, and the steady pulse of an engine between your legs.

Zen tells you to empty your mind. Motorcycles force you to sharpen it. Riding demands survival before it whispers meditation. Every curve insists on attention. Every patch of gravel or oil threatens to undo you. The survival scan roots itself: mirrors, shoulder checks, throttle control, the tilt of your head catching what others miss. On a bike you sit still and stay watchful, the way scripture commands: “Be sober, be vigilant.” Zen preaches release, but survival says: keep your eyes open.

Perhaps this is why I treat every car like an assassin. Drivers wrapped in cages lecture me on danger, but their machines carry the real menace. I’ve seen it too many times: the one with a phone propped on the wheel, the one drifting across the yellow line with a coffee in hand, the polite commuter who waves in the grocery store but forgets I exist on the bypass. Riding strips the paint from politeness. Behind calm eyes hides carelessness, even malice, revealed when someone pretends not to see or swerves close for sport. They call motorcycles dangerous, yet their inattention spills the blood.

And then the noise. Complaints usually come wrapped in questions: “Why do they have to be so loud?” The sound irritates them not because it deafens, but because it refuses to stay hidden. If you’re not staring into the illusion of safety inside your car, maybe you’ll hear me. Maybe the sound itself warns you: I ride here, too. Some people resent that reminder, but I trust the rumble more than their mirrors.

Birds teach the rest. They never perch as decoration; they signal. Sparrows scatter to warn of something unseen. Crows perch on fence posts, counting who passes. Hawks carve silent circles above prey that never looks up. Even starlings, those dark clouds that ripple and fold in the sky, move like living scripture, teaching vigilance through their endless adjustments. Scripture uses them this way too: sparrows known to God, ravens feeding Elijah, doves crossing impossible waters. Fragile and fierce, they bless and they warn.

In those moments riding local roads—past gray barns leaning in Shirland, through Rockton’s main street, along the hush of the Sugar—I hear the road preach its own scripture, not words on a page, but lessons in motion: balance, risk, endurance. The bike grafts me into the landscape, even as it forces me to remember how exposed I remain. Survival doesn’t interrupt the ride; it defines it.

On the bike I practice vigilance, eyes alive for every curve and threat. On foot, I read the aftermath: the trails left behind, the remnants of a struggle already lost. Riding teaches me to endure the present; walking teaches me to face what the present has already claimed.

The longer I ride, the more I live inside contradiction: the machine that carries me corrodes the world. Fuel that powers me fouls the air. Petrol poisons, and yet the engine delivers clarity. Survival never arrives pure. It always costs. Always mixes, always shadows. I breathe the fumes and grip the bars anyway, because in that mix rides something honest. Maybe that’s why the trail of feathers by the Sugar River still clings to me: it carried the same truth in another language.

Recently, I stopped where the river bent low, the bike ticking as it cooled. In the grass lay a scatter of feathers, a trail pulling into the trees—not the neat loss of a molt, but the scar of a struggle, a hunted creature fighting to the last. Something had taken its time, patient enough to pluck and tear before finishing the work. I stood over it longer than I meant to.

My own feathers lay in that trail: the ones ripped off by loss, by years when work devoured me, by nights when exhaustion outlasted sleep. Survival rarely looks clean; it rarely bows to dignity. I remembered the children I sat beside, how they too walked back into their lives missing pieces, marked but still standing. Their survival asked no permission, only bore the raw fact of tenacity.

Later, on a path I had walked several times, my stomach growled loud enough to startle me. It was not hunger, not really. Just a reminder: you are still flesh. There in the mulch and memory lay another ring of feathers beneath a split log, dark, striped, and torn. Turkey, maybe. Something once proud and winged, brought down in a hurry. You can read a whole story in feathers if you learn how to see: the flailing, the resistance, the silence that follows. I kept walking, past another tuft of down, then another. Every twenty feet, another trace. Whatever had done the killing had not rushed. Perhaps it lingered. Perhaps it came back later.

And I thought of the things I have left behind: the arguments, the bruises that do not turn blue. The conversations where someone meant well and still drew blood. Not everything torn from me was wrong to lose. There are kill sites in all of us, the places where old selves met tooth and claw, where belief gave way to truth, where we stopped flapping and started listening. Today it was feathers. Tomorrow it will be something else.

Still, I walk and then ride. Because nothing in nature apologizes for surviving.

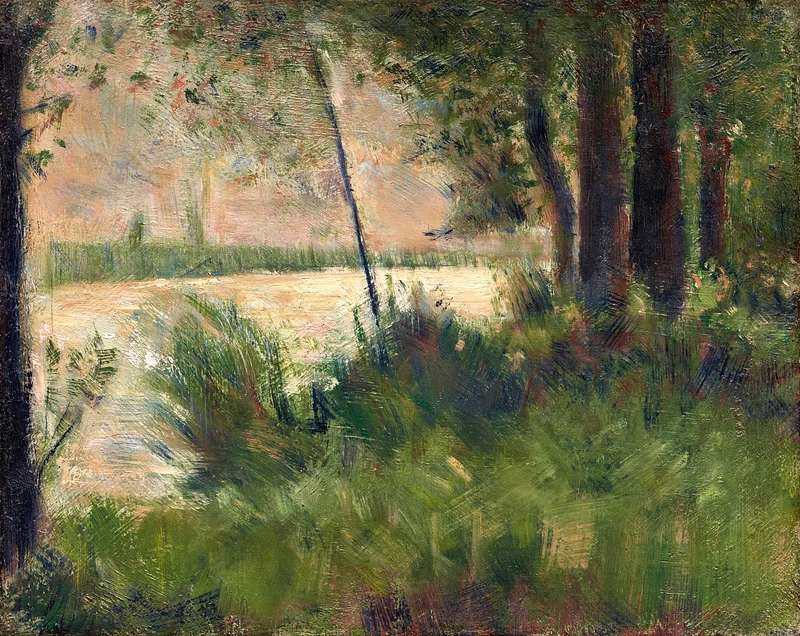

Image Credit: Georges Seurat, “Grassy Riverbank” (1881-1882) via rawpixel.