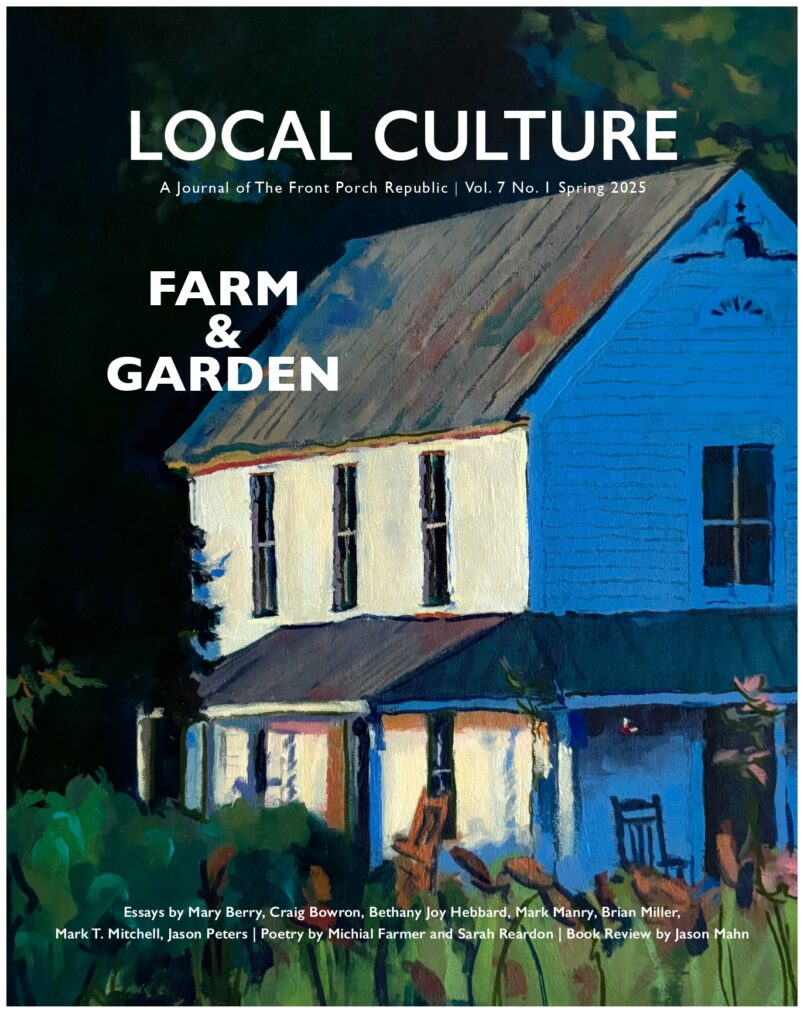

This is the editorial introduction to the latest issue of Local Culture. You can peruse the table of contents for this Farm and Garden issue, and if that whets your appetite, please subscribe.

The discipline of ends is no discipline at all. The end is preserved in the means; a desirable end may perish forever in the wrong means. Hope lives in the means, not the end.

—Wendell Berry, “Discipline and Hope” (A Continuous Harmony)

The spring rains this year wrote a message on the land: they told us, as they often do, where the waterways in the fields are. In my county a few of those waterways have been in grass for a long time and will remain in grass. That’s to someone’s credit. Many more waterways have been plowed straight through, fencerow to fencerow, as the saying goes, and planted in the rotational crop of the year, which, here as elsewhere, is either corn or soybeans. Wheat fields, though few, are in slightly better shape, and the fields in hay, though fewer still, give hope by holding fast to the loamy glebe. By holding fast they hold it in place.

But for the most part the collusion of water and gravity has done little to remind us, whether husbandman or onlooker, of a first principle: keep the ground covered. If you don’t, it will disappear.

Consider the lovely fertile state of Iowa, which, instead of feeding itself, imports about 90 percent of its food. (This did not change when one of its former governors became the U.S. Secretary of Agriculture.) Since the advent of industrial farming Iowa has spent nearly half of its original endowment in topsoil. Spent capital can’t produce interest, and almost everyone except politicians and other wastrels knows that you don’t touch the principal.

Or conduct an experiment with death. Find a hundred-year-old cemetery adjacent to a corn field and consider the elevation drop as you step from the dread abode to the Roundup-ready fields—that abode of even greater dread. Such studies in contrast are ubiquitous. There are three in my immediate vicinity. They are available to anyone who can be bothered to go out of doors and use his legs for something other than sitting on, and twice recently I have read accounts or heard of other wanderers among the mute inglorious Miltons who went sober in an instant when they saw the unmistakable signs of poor land-use and utter disregard for the earth’s precious outer layer. In one instance the field was a full 12 inches below the cemetery; in the other even more than a foot. The dead, who keep their soil in place, are trying to teach us something, and there is a way of articulating it: we ask the land to overproduce so we can (1) offset (but also further depress) low commodity prices and (2) pay for the machines and the energy that keeps the machines running. Thus do we enrich the corporations by impoverishing the land. The cost for this is topsoil. We export our own land in order to pay for the imports that destroy it.

This is the story, all over again, of the Trojan Horse and how it is that a whole people, dragging the treacherous thing through its own gates, invites and proves accomplice to its own destruction.

For a little perspective consider this: I recently removed a rain barrel near our henhouse in order to clean it. It had been in place for about 12 years, and on its top, where leaves and other organic matter and moisture had gathered all those years, there was a beautiful layer of black humus about an eighth of an inch thick. If my calculations are correct, building one whole inch of this humus would require, mutatis mutandis, another 84 years, for a total of 96. This accords with the generally agreed-upon estimates (though variable, certainly) that nature unaided can make an inch of soil in a century. That is more time by about two decades than it has taken Iowa to lose nearly half of its capital in topsoil. At nature’s pace, and assuming the most conservative estimates of total loss, restoring that endowment will require more than half a millennium. Grassed waterways or not, that’s a tall order for a nation untroubled by its own vast weedless annual monocultures.

It is worth pointing out that nature, left to herself, never farms this way. She prefers perennial polycultures and never excludes animals.

In preparing this issue of LC I wanted to corroborate some statistics on a chart that I keep tucked in one of my copies of The Unsettling of America, which everyone with a personal library should have a well-thumbed copy of. The chart is on a piece of paper, 8.5 x 11, and hand-written in pencil. Its main purpose is to remind me of the decline in the number of farms and farmers especially since the Second World War but also dating back to Civil War times. (I reproduce the chart, for what it’s worth, on page xx.) But since I don’t remember when I put the chart together and didn’t make a note of the sources from which I compiled it, I figured I should check its accuracy.

What did I find? Or, rather, what did I find instead?

An article in Forbes from 2024 reduces the data from the 2022 USDA Census of Agriculture to “nine takeaways,” which is good news for anyone happy to have the Explainers do his thinking for him: all the data have been distilled and interpreted. “What you need to know” is right there in pie charts, the McParagraphs of journalism.

Of course there is some useful, if alarming, information here. For example, 82.5% of farmland is held by farms of over 500 acres, and “although 70.5% of producers live on the farm with which they are involved, only 42% classify farming as their primary occupation.” Nearly 40% of farmers “say their work-life involves 200 or more days of an off-farm job.”

Someone to whom the “country” and “countryside” are not abstractions might be more than a little worried about the implications here, namely, that too much productive land, almost all of it in annual monocultures and Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), is in the hands of too few people and that for at least 40% of farmers the price of goods leaving the farm apparently can’t keep pace with the cost of goods coming onto it.

But on these matters the Explainer is silent.

We are also assured that “a good deal of farmland is rented[,] and that can be ok”—because the assurances of kindly land-use are as certain in rental- and lease-agreements as they are in actual ownership. Forget that this is a fantasy plainly false to anyone who has ever rented and then owned a house, or who has owned but also rented a car. Care and ownership go hand-in-hand.

And just when we think we might be coming upon an important observation—that there is “limited diversity” on farms—we learn that this has nothing to do with a variety of crops mixed with animals or of woodlot management and supplemental crafts. This paragraph is about race and sex—or, as we now say, “gender.” It’s about whites, blacks, males, females, Hispanics, Asians, Hawaiians, and “other Pacific Islanders,” etc., etc. In other words, it is not about biodiversity—the real diversity on which the fashionable manufactured academic sort depends.

Not content to be in high dudgeon, I kept reading. Without too much work I found another article also intended to keep us from thinking, this one “charting the essentials” of “ag and food statistics” and produced by none other than the USDA itself. It assures us that “rapidly falling farm numbers” between 1935 and the 1970s “reflected growing productivity in agriculture and increased nonfarm employment opportunities.”

This bland language, set in motion by the imprecise verb “reflected,” is little more than a tax levied on us by numbers-mad prevaricators and equivocators. Notice the complete lack of both agency and responsibility here. Notice the glaring absence of political culpability. The phrase “nonfarm employment opportunities” isn’t even shorthand for the official U.S. policy that caused the farm-to-city migration in that earlier period. The phrase is subterfuge. It is a cover for what actually happened, which was the introduction into farming of cheap energy, cheap money, manufactured fertility in the form of nitrogen-based fertilizers whose feedstock is natural gas, and especially large machinery. All these account for that “growing productivity,” and all were backed by the coercion of the “get-big-or-get-out” threats issuing from the federal government, a policy that was nothing less than a crime perpetrated by a government against its own people. All this and much more is entirely missing from an official publication of the USDA. And thus the history of farms, farming, and farmers gets elided by “nonfarm employment opportunities.”

Or, to put it another way, in the statistical measurements and in the mad endeavor to account for “gross cash farm income” from “commodity cash receipts, farm-related income, and Federal Government payments”—also known as Big Ag’s government-sponsored money-laundering program—there is no mention of the people, the actual people on the actual land, almost all of whom are perforce price-takers instead of price-makers.

But where are the people? What are they doing now that they’ve been liberated from their farms? What has happened to their communities and the businesses they supported and were supported by? They simply do not exist in the minds and imaginations of the Deciders and Explainers. And in a highly centralized bureaucratic state, in an economy with hoards of middlemen that keep producers and consumers out of sight and mind of each other, they hardly exist at all.

Insofar as the Deciders and Explainers know nothing or close to nothing about the land, the forests, the watersheds, the land-using people, the land-using communities, and the “neighborhoods” in the full sense of that word; and insofar as the governing and chattering classes refuse to acquaint themselves with the contingencies of the country not as an abstraction, and not as a dumb sum total, but as a mosaic of individual places, regions, and sections, each as distinct as a row in a backyard garden among many distinct backyard gardens; and insofar as the Deciders and Explainers have decided that they may legitimately live indoors forever, far from the weather, exempted from every part of the food economy except buying, eating, and excreting their food—insofar as they have committed these and many other offenses against nature and nature’s economy, they put the country, both the real country and their favored abstract one, in a bad way. Insofar as we all refuse to know the country, and I mean the extent of it, not the parts visible from airplanes and interstates, we behave badly.

Apparently technologically advanced adults have no need of Dante or the cultural tradition. They have AI.

Now it is a fact of the moral life that bad behavior is what puts you in a bad way. Children are supposed to learn that their misery—being sent to their rooms, for example—is a consequence of their behavior. The two things are related. The lesson here, which is nothing less than a first principle of the moral life, even as keeping the ground covered is a first principle of good farming, is that happiness correlates to obedience. Obedience leads as much to the beatific as disobedience to the miserific life. On this our cultural tradition is clear. Consult Dante for starters. But apparently technologically advanced adults have no need of Dante or the cultural tradition. They have AI. Someone should tell them they are putting themselves in a bad way; a bad way assuredly awaits them.

A mulish willed myopia at the elected end is no excuse for a lazy passivity at the voting end, and so, after all of this, I would remind myself and say plainly to others that nature, who tends to work from the ground up, has plenty to teach us about starting from below, whatever the Deciders and Explainers are doing up above. In this she is like the spring rains and the dead asleep in their raised beds. We can hope that people who like to eat will listen to her, that they will reenter the given world, acquaint themselves with the economy of nature about which the likes of Sir Albert Howard (The Soil and Health) and Gilbert White (The Natural History of Selbourne) were so articulate, and maybe even learn something—as did Howard and White—about the extent of their country. I would in no wise disparage that elegiac stroll through the elevated ground of a country churchyard or the single herb growing in a windowsill pot. “There is value in any experience,” Aldo Leopold wrote, “that reminds us of our dependency on the soil-plant-animal-man food chain, and of the fundamental organization of the biota. Civilization has so cluttered this elemental man-earth relation with gadgets and middlemen that awareness is growing dim”—or has all but gone out.

Although I see disturbing evidence of erosion all across the three contiguous counties that I traverse in going to and from home and classroom, the trek itself, because it is longer than I could wish it to be, and certainly longer than it should be, reveals to me other farms as well, other kinds of farms. Men in black broad-brim hats tend them. These are small, diversified, and lovely places. No derelict vehicles rusting in the weeds mar the view, and as you pass by you cannot help but think of the expense and trouble you yourself could save if you refused to buy, insure, license, maintain, and constantly gas up a mechanical Jacobin. I at least think this as I look out the windows of my own four-wheel revolutionary, my own tin tyrant.

There are pies and other goods for sale on front porches, and eggs too—better ones for less money than you can get them for at a grocery store, that enormity so different and so less humane than “your local grocer,” also a victim of erosion, though of another kind. Sheets and clothing dry at no expense on clothes lines, even in cool weather. No one farms without animals, and of course each farm keeps animals for traction. What few fields that are exposed are small enough to be worked by teams, and the soil is black and teeming, not gray like tree bark. The furrow lines lack the dull uniformity that suggests a large indifferent machine guided by GPS and satellites, the low blinking but untwinkling stars in our new astrology, more superstitious than the old. The people here live not only on but also in large measure from their farms. And this means they all have gardens. We who motor by might be tempted to call them Victory Gardens, inasmuch as the nation is perpetually at war and shows no signs of changing course, except you don’t get the sense that the war-faring state has anything to do with these gardens or the self-reliant people who keep them as a matter of course. Search how you may you will find few gadgets and no middlemen.

The news, in other words, is not all bad.

Spring can be niggardly in these parts, and this year she was about as stingy as I’ve seen her. But the place was ready for her when she finally did arrive. And now the spring lambs and the hogs are here. Every day the hens do the one thing we ask of them, and in exchange they receive room and board, nature herself providing most of the board. The garden is in. And, just to join the numbers-mad Explainers for a brief moment, I’ll add that 91.6% of the plants in the starter trays, planted in late winter, germinated. Until the weather turned warm enough for transplanting, they all stood in an east window, turning and leaning toward the light. Biologists claim to have discovered the “mechanism” that explains this phenomenon, but I think that, like the dead

Beneath those rugged elms … Where heaves the turf in many a mould’ring heap,

There is no law preventing us from being worthy pupils of the spring rains, the dead, and the plants.

the plants just wanted to teach us something. There is no law preventing us from being worthy pupils of the spring rains, the dead, and the plants. We can mind first principles; we can keep our hands off the principal.

The work of farm and garden always lies before us. It lies before anyone with soil and a pot and a seed. That work reminds us of our contingency and the need for vigilance, but it is joyous work. There is hope in it. Of course we hope for a harvest and for animals that fatten toward the supper table. But inasmuch as the ends are uncertain, we proceed according to the hope that lives in the means.

This issue marks the end of Sophie King’s tenure as my editorial assistant. I use the occasion to thank her for her excellent work, to wish her the best as she ventures off to graduate school, and also to welcome a new contributing artist, Mary Hannah Runge. This little publication, still yearning for a shoestring budget, has been blessed with a lot of unpaid talent. That includes the writers, current and past, whom I also wish to thank. And, as always, my sincere thanks to all of you faithful subscribers.

1 comment

Rob G

Bravo, Brother Peters. This will be getting wide circulation, at least from me.

Comments are closed.