Ambition has always held a complicated place within Western political life. Today ambition is almost a dirty little secret—a drive we are encouraged to veil, much like the Victorian who blushes at any unseemly subject. Those who openly declare their ambitions are either praised for innovation and self-reliance or denounced as power-hungry and dangerous, with little variation between these poles. If there exists a tradition that sees ambition as “the grand enemy of all peace,” a disruptive and potentially ruinous force, how can it ever be redeemed?

Yet ambitious figures continually arise. However warily they are received—or however artfully they attempt to disguise their drive—they are needed to inject energy into political life. Politics, at its best, requires those willing to risk greatness.

Aristotle’s framework offers an instructive starting point. Philotimia—literally, the love of honor—can denote both a virtuous ambition and its vicious excess. There is no distinct word for ambition rightly ordered and ambition gone awry; both wear the same name. Only the deficiency—lack of ambition—is separately labeled. This ambiguity reflects an enduring difficulty: how can a liberal and egalitarian society make peace with those individuals driven by an intense hunger for honor?

The American experience is no exception. Abigail Adams, writing to her husband during the birth of the republic, observed:

How difficult the task to quench the fire and the pride of private ambition, and to sacrifice ourselves and all our hopes and expectations to the public weal! How few have souls capable of so noble an undertaking

Even at the founding, ambition was recognized as both dangerous and necessary. The key lay in tempering the love of honor with love of country.

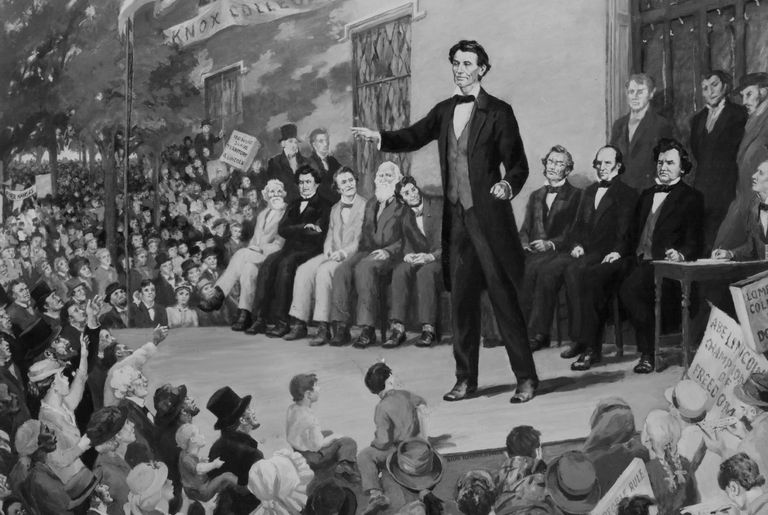

Perhaps no American figure better embodies this tension than Abraham Lincoln. Lincoln himself was no stranger to ambition. As one contemporary remarked, his drive was “a little engine that knew no rest.” He admitted as much early in his career, writing that every man has his peculiar ambition, and that his own was “to be truly esteemed of my fellow men by rendering myself worthy of their esteem.”

Yet Lincoln’s ambition was not a naked thirst for power. He publicly submitted his fate to the judgment of “the independent voters” of Sangamon County. If they elected him, he would labor unremittingly; if they did not, he would accept their verdict with humility. His ambition, he insisted, was inseparable from service to the people and the republic.

In his famous Lyceum Address, Lincoln gave a chilling warning about towering ambition:

Towering genius disdains a beaten path. It seeks regions hitherto unexplored. It thirsts and burns for distinction; and if possible, it will have it, whether at the expense of emancipating slaves or enslaving free men

Lincoln understood that ambition could build or destroy. He knew from early on that the drive for distinction could either save the republic—or shatter it.

Lincoln understood that ambition could build or destroy. He knew from early on that the drive for distinction could either save the republic—or shatter it.

The tragic dimension of Lincoln’s ambition has often been noted, not least by Lincoln himself. According to some biographers, Lincoln could “easily identify” with Macbeth, because he too possessed ambition “on the grandest scale.” As Matthew Pinsker has suggested, Lincoln fits the rare category of those who knew they were destined for greatness—not merely those who wanted or needed success.

The comparison to Macbeth is striking. Both men were driven by vaulting ambition. Both understood the terrible loneliness of leadership. Both met untimely deaths, viewed by their enemies as tyrants. Yet the differences are just as telling.

Where Macbeth’s ambition curdled into murderous vanity, Lincoln’s was tempered by a belief in something higher: the Union, the Constitution, and the cause of human freedom. Macbeth seized power by betrayal; Lincoln rose by consent. Still, Lincoln was fascinated by Shakespeare’s portrayal of ambition, guilt, and destiny.

To take a different play, Lincoln’s favorite passage from Hamlet was not the well-known “To be or not to be,” but Claudius’s anguished reflection on guilt:

O, my offense is rank, it smells to heaven… Is there not rain enough in the sweet heavens to wash it white as snow?

The weight of blood and guilt resonated with Lincoln as he presided over the bloodiest war in American history. Though he fought for a righteous cause, Lincoln—empathetic to the core—felt the heavy burden of the nation’s suffering.

Late in his presidency, Lincoln confessed:

Doesn’t it seem strange to you that I should be here? Doesn’t it strike you as queer that I, who couldn’t cut the head off a chicken, and who was sick at the sight of blood, should be cast into the middle of a great war?

In the Shakespearean sense, Lincoln understood leadership as a tragic role: greatness entwined with sorrow.

More haunting still was Lincoln’s affinity for Macbeth’s final soliloquy:

Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time.

Here Macbeth laments the futility of human striving—realizing too late that even supreme political power cannot stave off despair. Lincoln, facing the horrors of war and the limits of human control, found himself drawn to these lines, perhaps recognizing that destiny, once unleashed, cares little for individual intentions. Unlike Macbeth, Lincoln bore no conscious guilt. But he shared Macbeth’s realization that leaders are caught in vast, impersonal forces beyond their making.

Lincoln’s fatalism was no literary pose. Throughout his life, he articulated a deep belief in what he called the “Doctrine of Necessity”—the idea that human action is shaped and constrained by forces beyond our control. As he once put it:

Things were to be, and they came, irresistibly came, doomed to come… Men are made as they are made by superior conditions… [Man] is simply a tool, a mere cog in the wheel.

Lincoln saw himself as an accidental instrument, temporarily elevated by circumstances rather than personal merit alone. In an 1864 letter he confessed, “I claim not to have controlled events, but confess plainly that events have controlled me.”

Yet Lincoln did not use fatalism as an excuse for passivity. He acknowledged his own ambition, admitting he had “never professed an indifference to the honors of official station.” But he also insisted that his highest loyalty was to “the republican cause” not personal glory.

Lincoln’s ambition was vast, but it was yoked—by conviction, by circumstance, perhaps by grace—to the service of something greater than himself. If human beings are indeed cogs in a vast machine, Lincoln’s faith held that the machine itself was animated by providence. His ambition, then, was not simply personal striving but participation in a larger, almost divine drama. Like a tragic hero, he fulfilled his role, even at the cost of his life.

Lincoln’s life reveals the double-edged nature of ambition in democratic governance. Ambition can destroy republics—but it can also save them. Democracy cannot thrive on mediocrity alone. It requires leaders willing to risk greatness. Yet that greatness must be tempered—by devotion to the common good, by humility before the people, and by loyalty to principles that transcend personal fame.

Lincoln’s ambition, rightly understood, was not merely a private hunger but a profound act of faith: faith in the Constitution, in the Union, and in the enduring potential of democracy itself. His assassination, carried out in tragic, almost Shakespearean fashion, sealed his legacy as both hero and sacrifice.

In reflecting on Lincoln, we are reminded that ambition is not an alien threat to democracy. It is democracy’s greatest risk—and its greatest hope. The challenge is not to extinguish ambition but to educate it, channel it, and bind it to the service of the common good.

Politics, at its best, requires those willing to risk greatness. Vaulting ambition can destroy. But rightly ordered, it can also lift a nation from darkness into new life. Lincoln’s life stands as a testament to that uneasy, necessary truth.

1 comment

Mark Botts

Well done, Raleigh. I plan make this essay of yours required reading for students of mine when they study Macbeth and several of Lincoln’s works. The argument brings to mind, also, David of the Old Testament and Paul of the New Testament. Really enjoyed the piece. Thank you.

Comments are closed.