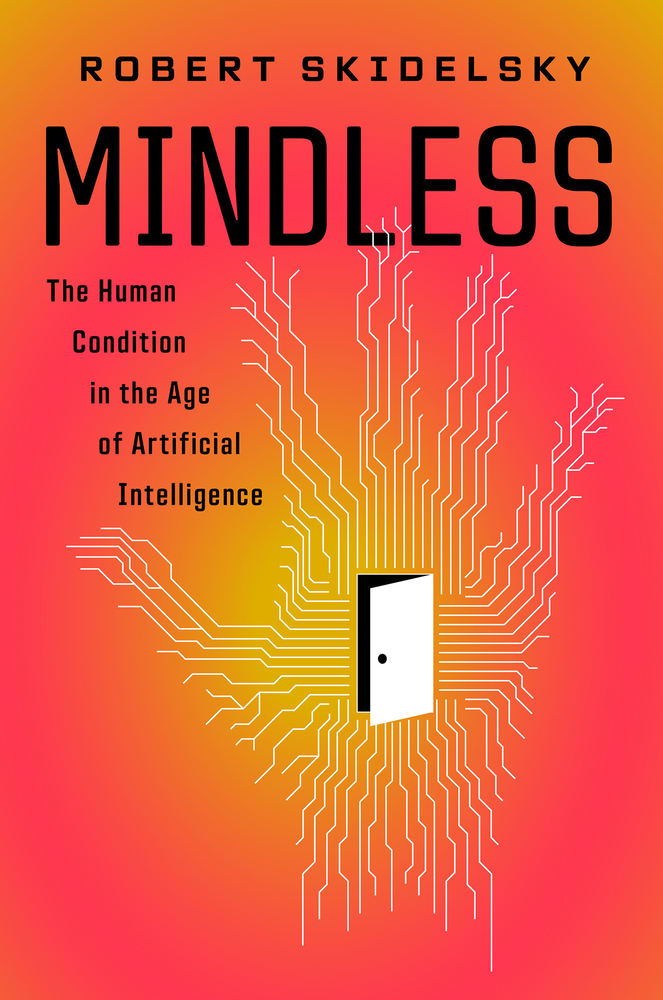

Internationally recognized economic historian Robert Skidelsky has thrown his hat into the ring on the question of AI and the future of civilization. Mindless: The Human Condition in the Age of Artificial Intelligence is a sweeping treatment of the history of economic change and technological advancements and how such things intersect with political and religious systems, art and literature, and human nature itself. Skidelsky’s expertise is on full display as he tells the story of the impact of machines on the human condition. He highlights three primary lanes of impact: “on the way we work, on the way we live and on our possible future” (1). Throughout he draws attention to what we might call a technological paradox: “every increase in our own freedom to choose our circumstances seem to increase the power of technology to control those circumstances” (1).

Having reached the twilight of his long academic career at the University of Warwick, Skidelsky reflects on what advice he should give his grandchildren, and sees two alternatives. “We can either urge them to seek technical solutions for the variety of life-threatening risks which present technology will bequeath to them or we can urge them to reduce their dependence on machines” (5). He argues throughout the book that “the first endeavor, while it might salvage fragments of human life, will destroy everything that gives value to it. The second alternative is the only one that makes human sense, but it requires the recovery of a framework of thought, in which religion and science both play their part in directing human life” (5).

He is not optimistic, however, for a wide-scale adoption of the second alternative which he hopes his grandchildren pursue. And that was the sense I had when I finished the book. This frequently happens with books in this genre. To a certain extent, the easy part is diagnosis; the hard part is what to do about it. It was the same feeling I had when I finished Antón Barba-Kay’s stinging critique of digital technology in A Web of Our Own Making, which ends with no real answer.

I can relate to this challenge of offering an answer and alternative to our technological dilemmas. In writing Are We All Cyborgs Now? with Robin Phillips, we were cognizant of this general weakness of the tech-critique genre and were intentional in offering real advice and alternatives. Yet a large part of our book was still taken up with diagnosis rather than cure. Perhaps this happens so easily because the cure is so mundane. It is not glamorous or exciting to tell people to make hard decisions, to opt-out of certain things, to choose the path of more resistance, to do the hard work of life together, to maintain their friendships, to develop their human capacities, to care for one another. Yet it is in such boring, slow, and simple things that we grow as people and are formed in virtue and wisdom, which is exactly what we need to withstand the machine age. And Skidelsky’s book points us in that direction, too.

Highlights

Skidelsky’s expertise in economics and history make for a compelling storyline that traces the impact of mechanization and automation on human work and life. And he seamlessly ties together such economic and historical changes with art, literature, and religion. Though I consider myself a lifelong student of the history and philosophy of technology, I found myself writing down new names and new book titles to explore further. I especially liked his chapter explaining the role of utopian and dystopian literature in responding to technological change, which wove together a fascinating and wide-ranging tour of the genre. His summary: “it is easy to slide from democracy to dictatorship because the technology of power creeps up so invisibly and becomes so pervasive that most people remain blissfully unaware that it is happening” (206).

The British professor highlights how the current wave of automation “differs from that of previous technological upheavals by automating mental work in addition to manual work. Not only does technology bite ever deeper into cognitive work, but it does so at an accelerating rate” (109). He wonders “what effect the structure of employment in a country has on its political system” and if this wave of automation in the AI age “promotes a structure of occupations inimical to the survival of liberal democracy” (112). He warns that “we have scarcely yet faced up to the psychological and political consequences of creating a partly redundant working-age population” (253).

Skidelsky wonders if Frederick Winslow Taylor’s scientific management applied to our digital ecosystem has turned us into nothing more than electronic representations of human beings, data bits to be mined, information-terminals to be optimized under the reign of “digital Taylorism.”

Skidelsky challenges the assumption of techno-optimists that “machines will enhance human capacity,” arguing that “the world of work in the machine age is a world of lost skills” (114). He contests the tacit idea built into the push for automation that efficiency is the highest good. And he wonders if Frederick Winslow Taylor’s scientific management applied to our digital ecosystem has turned us into nothing more than electronic representations of human beings, data bits to be mined, information-terminals to be optimized under the reign of “digital Taylorism” (117).

The author also points out how the Enlightenment, Scientific Revolution, and Industrial Revolution all in concert made a certain understanding of the world and of human beings seem intuitive and natural. Namely, a mechanistic view of the universe, with man as machine. He writes, “the mechanical metaphor was especially seductive because it introduced a vocabulary for discussing human problems as engineering problems” (130). Over time, this mindset makes everything a problem of information or data, of scientific measurement and analysis. Farewell religion, art, theology, and philosophy, and make way for Big Data.

But what once seemed like only a dream or metaphor, became a reality as computing technology advanced. Skidelsky deftly tells the story of “the steady realization by computer scientists that virtually anything can be represented digitally—as a series of discrete variables—and thus, that virtually anything can be represented by a computer. Conversely, anything which cannot be computerized—like a belief system—was robbed of ‘value’” (212). As computational power has surpassed human ability in many domains, the push to turn everything into data focused on data-fying the human being—especially the “behavioral surplus” data from their online activity, an information-commodity desired by governments and companies.

In a certain way, all this finds its current apogee in AI, which Skidelsky deals with more directly in the book’s final sections. He contends that there is still a unique role for humanity based on consciousness. “Intelligence of the kind we recognize as human is inextricably associated with consciousness—not just being able to do something or many things efficiently, but being aware of what one is doing, having an attitude to it, positive or negative. The distinction we are looking for is between a brain and a mind. The question is whether it is possible for a robot to have not a brain of its own, but a mind of its own” (22).

He points out the materialist shortcoming of many AI advocates. As the weaknesses of “this kind of hard-line materialism becomes ever more clear, philosophers and scientists have had to work overtime to fit consciousness into their physicalist schema. One can’t help but feel that someday soon the house of cards that they have built will come tumbling down” (225). He also offers strong criticism of attempts to reign in AI by programming it in accord with ethical limits or moral rules. When our society functions in large part on subjectivist morals, where each person has their own truth, there is no objective moral basis upon which AI could be trained.

Criticism

The book’s grand narrative approach is both a strength and a weakness. On the one hand, it provides a compelling storyline that connects the dots between various fields of study and various movements and innovations over time. However, it runs the risk of being too simplistic, or becoming history on paper. Any reader with a specific area of expertise might quibble with some of his generalizations or the causal links he suggests. As a student of theology and church history, I found some of his theological commentary and perspectives on church history or doctrine sloppy or simplistic (especially on the Fall, Augustine, Luther, and the Reformation).

Skidelsky readily acknowledges that his generalist approach “trespasses on highly specialized fields of study and is open to the criticisms that scholars usually level against intruders into their protected domains” (6). But he argues that his book’s topic is ideally suited for a generalist who can bring to bear the insights of history, economics, philosophy, and theology. I agree that the questions we face in the digital age converge at the intersections of all these fields and require us to do inter-disciplinary work. I attempt to do some of that work myself, and am sure I open myself to the same criticism I’ve given here.

Another spot I thought was an oversight was in his concluding section when he describes the major potential catastrophes we might have to face down. He focuses on four existential challenges: nuclear proliferation, global warming, pandemics, and dependency on network technologies (249). Especially considering that the book is a treatment of technological change and its impact on societies, it would seem that a major relevant existential threat is what we are seeing signs of in countries like Korea, Japan, and many technologically-advanced nations, where population is declining, and marriage rates and family formation are in freefall as people are turning to digital replacements and simulations for human relationship, companionship, and even sex. The role of digital technology and AI as a major contributor to this development could have fit within his narrative.

There are many other lines of argument the book advances and worthwhile discoveries for readers as Skidelsky gives his telling of the story of humanity and technology. But I hope we can come up with more to say and do about it.

Image via pexels

2 comments

Grant Castillou

It’s becoming clear that with all the brain and consciousness theories out there, the proof will be in the pudding. By this I mean, can any particular theory be used to create a human adult level conscious machine. My bet is on the late Gerald Edelman’s Extended Theory of Neuronal Group Selection. The lead group in robotics based on this theory is the Neurorobotics Lab at UC at Irvine. Dr. Edelman distinguished between primary consciousness, which came first in evolution, and that humans share with other conscious animals, and higher order consciousness, which came to only humans with the acquisition of language. A machine with only primary consciousness will probably have to come first.

What I find special about the TNGS is the Darwin series of automata created at the Neurosciences Institute by Dr. Edelman and his colleagues in the 1990’s and 2000’s. These machines perform in the real world, not in a restricted simulated world, and display convincing physical behavior indicative of higher psychological functions necessary for consciousness, such as perceptual categorization, memory, and learning. They are based on realistic models of the parts of the biological brain that the theory claims subserve these functions. The extended TNGS allows for the emergence of consciousness based only on further evolutionary development of the brain areas responsible for these functions, in a parsimonious way. No other research I’ve encountered is anywhere near as convincing.

I post because on almost every video and article about the brain and consciousness that I encounter, the attitude seems to be that we still know next to nothing about how the brain and consciousness work; that there’s lots of data but no unifying theory. I believe the extended TNGS is that theory. My motivation is to keep that theory in front of the public. And obviously, I consider it the route to a truly conscious machine, primary and higher-order.

My advice to people who want to create a conscious machine is to seriously ground themselves in the extended TNGS and the Darwin automata first, and proceed from there, by applying to Jeff Krichmar’s lab at UC Irvine, possibly. Dr. Edelman’s roadmap to a conscious machine is at https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.10461, and here is a video of Jeff Krichmar talking about some of the Darwin automata, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J7Uh9phc1Ow

Rob G

Just a note to say that Mindless was originally published in 2023 in the UK under the title The Machine Age, and can be easily obtained from online sources under that title as well.

And speaking of Skidelsky, FPR readers might be interested in looking at his fine little book from a few years back, What’s Wrong With Economics?

Comments are closed.