Cleeve Hill, Gloucestershire. On the way to St. Martin’s I walked a fine road, shaded by oak and ash, lined with handsome dry-stone walls and wooden fences which trellised vines dotted with bursts of summer color. Cottages, attractive and fitted in their Cotswold stone, hugged the hedgerowed hills, nestled into lush, varied vegetation where even the shrubs are of interest. The road wound politely around homes with apparent deference to their primacy. The way hardly even resembled a road by American sensibilities, which I grew up experiencing as straight, sweeping, immovable, expedient things too dangerous to walk. Mathematical ideals dissolved delightfully before me as the road unfolded, calling Burke’s war on symmetry to mind. The gradual development of this place revealed a character tangible and indisputable, more stirring than all the pleasing sharp lines and perfect ratios in the world.

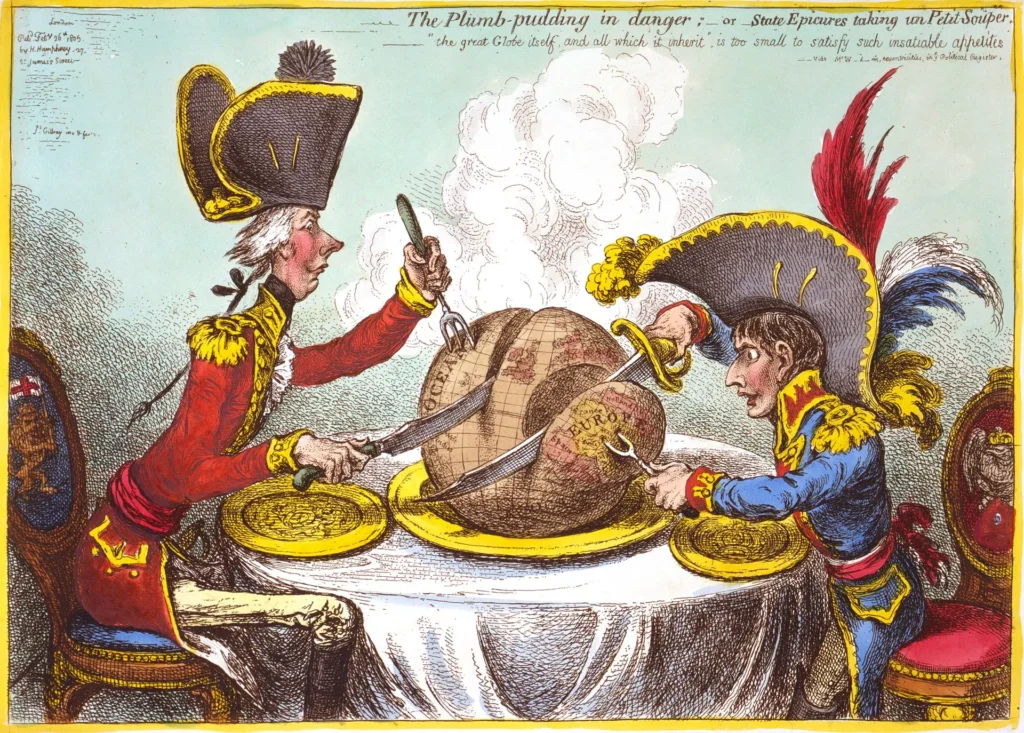

I had resolved not to romanticize a place not my own, not to indulge the dream that I could escape the deficiencies of my Pittsboro, where—at that very moment—comically evil developers are carving out her heart in a reenactment of the Plumb-pudding in danger. My first walk laughed in the face of this resolution, though I had not yet seen a sunset on Gloucestershire soil. Having succumbed to the enthralling pull of this beautiful place, the dissolution of my resolve promised an escapist fantasy but instead left an inescapable reminder of loss. I bridle at my disloyal nature, reminding myself that my hometown is not to be faulted for the lustful avarice of her assailants. I suffer at the bedside of a long-dying loved one facing the last, a perfidious wretch left with the warring pangs of wanting the misery over with and the putrid shame of willing the end…love is not love/Which alters when it alteration finds,/Or bends with the remover to remove…

I had a map, a destination, and miles to go on unfamiliar ground to meet a local friend at St. Martin’s Church. Without any means of contacting him or GPS to lead me, the question of my arrival remained unsettled as the sun sank and the miles wore on over unfamiliar roads. I walked on, hoping to soon see the tower of the church on the lone hill where it ought to be. Brambles bid me stay as I pressed on through the village of Bishop’s Cleeve. There was no orchestra of Carolina summer creatures, the cicadas and crickets of home; only the occasional mournful calls of wood pigeons broke the silence. This journey had worn in my imagination like a well-loved record, and reality’s remarkable resemblance to my visions did not help to ease the disquiet of walking through a dream. Gloucestershire was just how I had thought it would be, only now it was before me and around me and in me, feeling both more real and more fantastic. My heart quickened with each twist in the road as daylight softened into twilight. A break in the wood to my right and the tower suddenly stood above me, stark and close and real.

My journey from St. Martin’s was entirely different, led by my friend familiar with the land and the ways of moving through it. When we left the churchyard, he guided us off the road without delay, onto footpaths and through woods, fields, and streams. A world within the margins of roads emerged, a world with thick undergrowth and changing terrain. Britain’s rights of way and land access customs, like the common land tradition, give citizens the “right to roam” across the country, including (in some cases) private land. This tradition brought us along footpaths through golden wheat fields, stiles, gates, and other obstacles designed for overcoming. Small signs marked some of the footpaths at their entrances, but others bore only the marks of past presence. When the wood deepened, the clean wearing of the earth itself wore away into indistinguishable concord. But that doesn’t matter much when you know the paths, when you know your place, when your familiarity bestows free movement and easy, thoughtless steps because your body knows the way.

That kind of knowledge can’t be told but must be lived and acquired over time. I remembered my childhood forest, each differentiated paper birch, each fallen log, each dip of the creek, each patch of clay identical to outsiders, yet so distinct to me. The only byways in that wood were the ones we made, winding around trees and up rocks and back down again. With only the forest around me, getting home was as simple as if the heavens had illuminated the way. I no longer have that place, nor the familiarity of what had once been my wood, after a decade and several moves. The loss stung as I followed one who still had that sense of knowing movement.

There is a time and a place for roads. There are better roads and worse roads. The roads that took me to St. Martin’s were the best of their kind. By their very constitution, however, roads are not paths. As is so often the case, Wendell Berry puts it best:

The difference between a path and a road is not only the obvious one. A path is little more than a habit that comes with knowledge of a place. It is a sort of ritual of familiarity. As a form, it is a form of contact with a known landscape. It is not destructive. It is the perfect adaptation, through experience and familiarity, of movement to place; it obeys the natural contours; such obstacles as it meets it goes around. A road, on the other hand, even the most primitive road, embodies a resistance against the landscape. Its reason is not simply the necessity for movement, but haste. Its wish is to avoid contact with the landscape; it seeks so far as possible to go over the country, rather than through it; its aspiration, as we see clearly in the example of our modern freeways, is to be a bridge; its tendency is to translate place into space in order to traverse it with the least effort. It is destructive, seeking to remove or destroy all obstacles in its way. The primitive road advanced by the destruction of the forest; modern roads advance by the destruction of topography.

While the lovely roads got me to St. Martin’s, the paths blessed me with a taste of Gloucestershire’s true being, with how it might feel to know and love this place. A Native Hill tried to teach me this truth long ago, but like so much wisdom that’s often and lovingly wasted on me, I’ve only come to know it by experience. I know it now by the way from St. Martin’s.

I wonder what paths there are to explore at home in Pittsboro, or what paths I might make by habit and knowledge of my place. Though Pittsboro languishes towards her seeming end, perhaps she’ll outlive me. Is winter really death, and spring a rebirth? Are the trees that drop their leaves new trees by May? When Pittsboro falls to the fate of her Eastern neighbors, Cary and Apex, will she cease to be herself because she’s not as I want her? Burke asserts that we must obey the great law of change, that change is the means through which we conserve. After all, paths must balance respect for the past with needs of the future, adapting over time in a marriage of utility and habit. My place will change; perhaps it will die. My only recourse is love. Roger Scruton writes that “the transience of human goods does not make conservatism futile, any more than medicine is futile, simply because ‘in the long run we are all dead’, as Keynes famously put it. Rather, we should recognize the wisdom of Lord Salisbury’s terse summary of his philosophy and accept that ‘delay is life’.” Even while I grieve my changing home, the end of my place as I now know it, there are paths to be found and trod as we live together as finite creatures, rejoicing—however briefly—in the gift of our ephemeral being.

Image Credits:

Picryl

Wikipedia

Madeleine Austin

4 comments

Ralph Brown

We share experiences as students in Lex. Va. I at W&L at a time when there were fewer cars and walking was common and quite pleasant. More than fifty years later, I will think often of the charm and joy of sauntering the paths of Rockbridge City. Thanks for a the lovely scripted ramble.

Madeleine Austin

Thank you, kindly. Yes, all places change…I too love Lexington and Rockbridge. I’ve always wondered what it might have been like fifty years ago, and what it might be fifty years from now. Thank you for reading the essay; I’m so pleased that you enjoyed it.

Rob G

Lovely piece. It prompted a thought about the U.S. vs. the English landscape — we here in the States have roads and trails galore but not much by way of paths. And although I’ve had no time to think about it, there seems to be more going on here than just a difference in nomenclature.

When I was a child I lived next to a stand of woods with a small creek at the bottom, and there were three main paths through the woods, with several smaller offshoots. Nearly 60 years on those woods are still there, but I wonder about the paths. I’m still in driving distance of where I grew up. Maybe some clear fall day I’ll take a ride over and have a look.

I recall with some humor that one of the neighborhood boys, who was a bit of a rough-and-tumble outdoorsy sort (he was the lone Cub Scout in the neighborhood, if I remember correctly) had the last name of Pfaff, pronounced ‘Paff.’ We pre-readers all believed that his last name was ‘Path’ and that this was undoubtedly connected to his perceived woodsmanship. I remember declaiming at around age five that “His name is Chris Path, because he’s the one who finds all the paths.”

I’m also brought to mind of the fact that the UK publisher Little Toller, a wonderful outfit, has just reprinted Kim Taplin’s 1979 book The English Path, which I’ve bought but haven’t read yet. I’d heard of this book years ago but had forgotten about it, so was happy to be reminded by Little Toller’s news of the reissue.

Madeleine Austin

Thank you so much for this thoughtful comment, which gifted both a chuckle and a new reading recommendation! You’ve got it exactly–there is something more going on–and the same thoughts are bouncing around my mind. This is an attempt to parse some of them out. I really appreciate that you took the time to add to the conversation. I hope “Path” is doing well, wherever he’s wandered to.