As I drove into a hotel parking garage one afternoon, I mentioned to the attendant that I had come for a conference on John Milton. “Milton?” he replied. “Wasn’t he the one who had Satan say it’s better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven?” Yes, I said, that’s the guy!

If I had any doubts that Milton’s twelve-book, epic poem Paradise Lost was still relevant in twenty-first-century America, this parking garage attendant dispelled them entirely. However challenging the poem might be to read, Paradise Lost is a book that still matters.

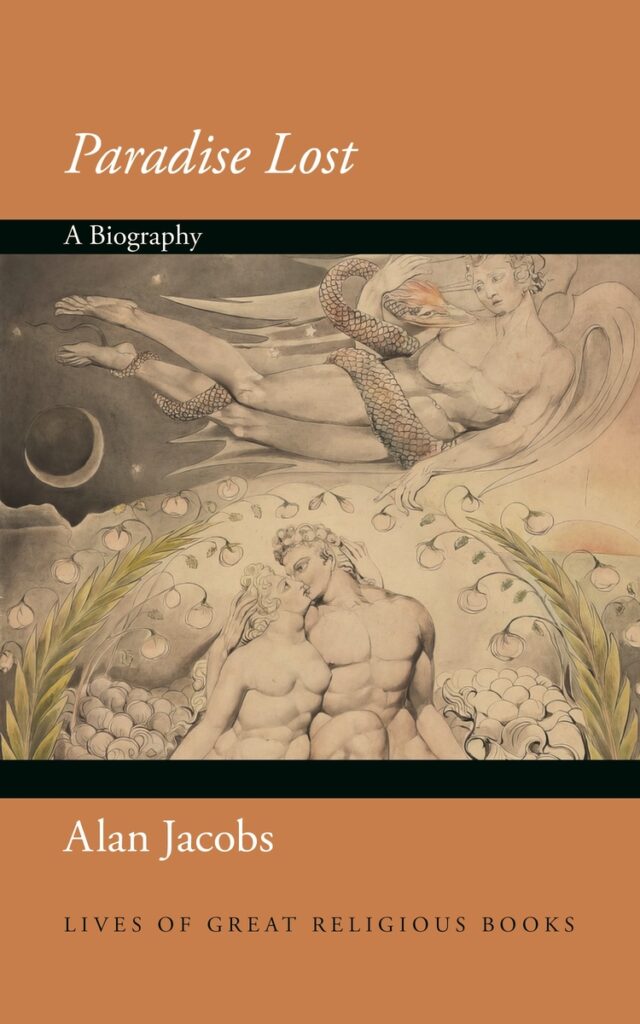

Fortunately, for new and veteran readers of the epic alike, Alan Jacobs has published a superb introduction: Paradise Lost: A Biography. For anyone who endeavors to read or teach Paradise Lost for the first time, I could hardly imagine a better single-volume guide to the work’s author, context, themes, and significance. Jacobs’s book isn’t a running commentary on the text of the poem, but it is an accessible and engagingly written overview of why and how Paradise Lost has been read since its first publication in 1667.

Although the book is part of Princeton University Press’s Lives of Great Religious Books series, Jacobs admits that Paradise Lost is not a devotional work yet maintains it is nevertheless a profoundly religious book. Surely Milton hoped that his epic would be received not so much as an aid to prayer but as a work of theological insight into the nature of God, Satan, humanity, and the Bible.

But as Jacobs acknowledges, the epic is seldom read even religiously now. Paradise Lost has been confined to a literary canon where poets and novelists riff on its imagery while scholars argue about the significance of particular passages. As Jacobs demonstrates, those who take Paradise Lost most seriously have not generally been the epic’s most pious readers. In an ironic twist of fate that Milton surely never saw coming, his epic has been taken up largely by heterodox or even anti-religious literati, from William Blake to Philip Pullman. Jacobs deftly tells us how that happened.

The book begins with a biography of John Milton himself. Judgments of the epic, Jacobs observes, have often been bound up with judgments of what we know (or think we know) about its author. Jacobs also succinctly explains the political and religious context of Milton’s life in seventeenth-century England—no small feat, that! Milton’s overarching concern, Jacobs argues, was always the defense of liberty, an ideal that would endear Milton to a fledgling American experiment over a century later.

Jacobs’s brief overview of the poem itself is remarkable. He compares the poem’s structure to the four parts of a symphony: the first movement (books 1-3) begins andante but concludes in a presto mood. The large central movement (books 4-8) moves at an allegro pace. The third movement (book 9) is the tragic largo maestoso hinge of the whole symphony, and the fourth movement (books 10-12) brings us through the andante denouement. Milton was a lover of music, and I think he would have approved of the analogy.

Like a symphony, the epic is deliberately and beautifully constructed. Yet when readers approach the epic for the first time, they may well feel that it is haphazardly arranged. Like its epic predecessors—the Iliad, the Odyssey, and the Aeneid—the plan of Paradise Lost is not obvious, and it takes a good deal of reading through it (and probably teaching through it) before one can confidently point out the great movements, the hinge points between them, and how the big pieces fit together. Jacobs’s symphonic analogy should help readers keep the greater plan of the epic in view as they read.

From his overview of the poem, Jacobs proceeds to tell us how Paradise Lost almost didn’t become a classic of English literature. Early readers agreed that it was a literary masterpiece, but many objected to the politics of its author. Eighteenth-century Torries like Samuel Johnson, for example, could not forgive Milton for supporting the execution of King Charles I at the end of the English Civil Wars. Critics also questioned Milton’s use of the epic genre to retell the story of the Fall of Man. Adam does not seem heroic, either in Genesis or in Paradise Lost. All he does is make a single wrong choice that inadvertently dooms the whole human race to misery and death. How is this character heroic, exactly?

The English Romantics had an innovative answer. For the poet and illustrator William Blake, it was not Adam but Satan who was the great unsung hero of Paradise Lost, despite Milton’s conscious intentions. Readers of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, on the other hand, will remember what an important part Paradise Lost plays in that novel. The monster, having learned human language, stumbles upon a copy of Paradise Lost and identifies with Adam, understanding himself as a new creation. But when Dr. Frankenstein refuses to make him a mate, he decides that he is not a new Adam but a new Satan, and he goes on a vengeful crime spree to destroy his maker and everything his maker holds dear. For the Romantics, Milton became the champion of artistic power and freedom from tyranny, including what the most radical of them construed as the tyranny of God.

Jacobs shows us how, in the centuries that followed, Paradise Lost migrated from the revolutionary’s bookshelf to academic conferences. Although modernists like Virginia Woolf and T. S. Eliot denounced Milton for both his substance and his style, it was partly the Inklings, Charles Williams and C. S. Lewis in particular, who rehabilitated Milton for a modern, academic readership. From there, Jacobs briefly introduces us to the main threads of Milton criticism that followed—C. S. Lewis, William Empson, Stanley Fish, and a few others—but without getting us lost in the mazes of contemporary Milton scholarship.

Jacobs ends the book by asking whether Paradise Lost has any future outside of academic scholarship. He suggests that yes, it might. Although Christianity seems to be shrinking culturally in the West, it is growing in the Global South. Who knows what new readers of Paradise Lost might emerge in those contexts, especially where the English language is widely spoken? After all, if a parking garage attendant in an American city still knows who Milton is, there is hope that Paradise Lost will continue to find admiring readers in the twenty-first century.

Image Credit: Plate designed and engraved by John Martin. “The Paradise Lost of John Milton with Illustrations by John Martin” (1846) via Wikimedia.