Dante’s Footsteps, a new collection of poems and reflections from Paul Krause, offers a winding and artful overview of poetry’s place in the contemporary world. His erudition and clarity keep the work mostly compelling. The book includes his own poems and four reflective essays on poignant poetry. Krause underscores in the collection’s introduction that “poetry is at the heart of human nature and civilization,” and that “the very apogee of the civilization in question inevitably converges with the age of poetic acme,” a posture toward the arts that may be essential for the revival of genuine culture.

Building on this framing, Krause traces the roots of poetry and its enduring significance across civilizations. The rise of Hellenic civilization, Krause claims, began not with philosophy but with Hesiod, Homer, and Sappho. He sees the same pattern in Rome and in the flowering of English letters. This historical framing is persuasive, highlighting how poetry has shaped civilizations in ways that philosophical discourse alone could not.

For Krause, poetry has always been about love—about the heavens and the burning passion of the human heart that thirsts after the embodiment of Love itself. This longing, he argues, anticipates the coming of Christ, as books like Ecclesiastes, the Song of Solomon, and Sirach proleptically announce the Word made flesh. All of literature and poetry, in this view, gesture toward incarnation: “it has long been the desire for Love that has moved the poets to capture the universal yearning of the human heart.”

From this historical perspective, Krause argues that poetry’s purpose lies not merely in artistic expression but in orienting the human heart toward Love and the Divine. Krause further insists that language not oriented toward Love is dead language, destined to dissipate. While this assertion may strike some readers as idealistic, it underscores the spiritual and moral stakes Krause attaches to poetic practice. If there is to be a spiritual resurrection, it will come through this literary orientation to Love, which alone can heal the modern malaise. Such, he says, is the pattern of history: “a poetic civilization aimed at Love flourishes.” For Krause, the task of Christians and others who want to tend culture is to reclaim this poetic orientation toward Love as the key to cultural renewal.

Having established his vision of poetry in the essays, Krause turns to his own verse to embody these convictions. His poems fit into the categories nature, ballads, culture, and metaphysical. Throughout, Krause’s fixation upon the Heavens and embodiment of love sings through. For example, in “Dance of the Sky,” Krause writes,

As I look up at the stars That sing to me from afar I dwell in that spirit divine Giving life to this soul of mine

Throughout his poetry, whether he’s describing the night sky or glorious friendship or battle, Krause is oriented to the higher things: to the good, true, and beautiful. Perhaps the pinnacle of his poems, and the one from which the collection takes its name, is “Dante’s Footsteps.” The poem reads as a retelling of Dante’s journey unto the Heavens, of “Climbing towards Mother Mary.” However, the journey is treacherous, and the speaker’s “painful days never end / Trapped in darkness without friends, / Underneath rock and thunder, / Wailing screams without wonder.” The poem is not only an aesthetic success but also encapsulates the transgressions and tribulations, in the case of Dante the mountain that must be climbed to reach the Divine, that characterize human life.

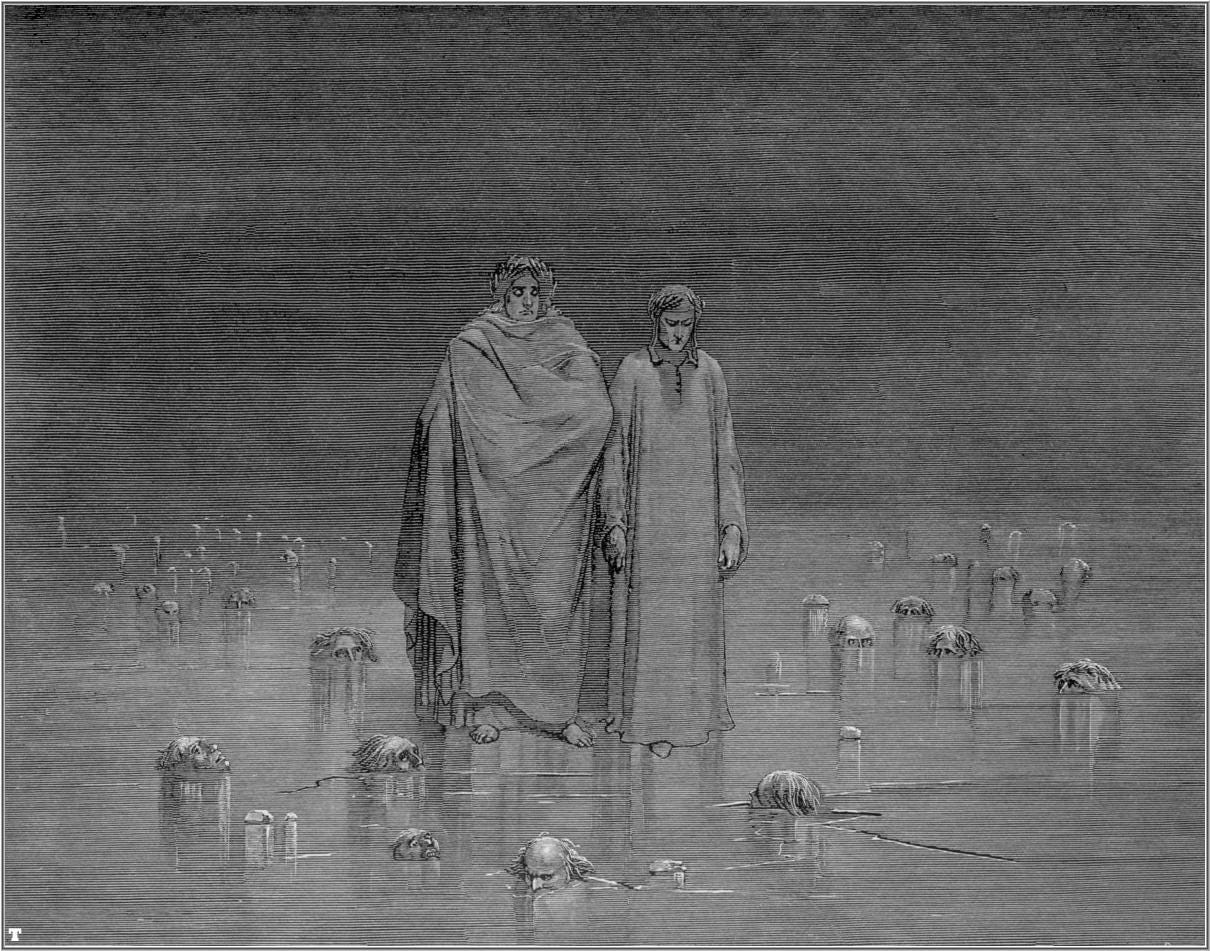

After exploring his own verse, Krause returns to reflective essays, connecting his poetic vision to broader literary and spiritual questions. The book concludes with four essays reflecting on “Homer and Love,” “Virgil and Christian Imagination,” “Dante and the Digital Inferno,” and “The Politics of Romantic Poetry.” The best of these essays is “Dante and the Digital Inferno.” This essay is particularly engaging, as it creatively bridges medieval literature with contemporary digital culture, demonstrating Krause’s ability to make classical texts speak into today’s concerns. As the title suggests, the essay revolves around the question of how “Dante is once again journeying through hell. This time without Virgil as a guide or a literate audience knowing his references, allusions, and cultural inheritance.” Rather, “the inferno of social media has Dante wandering astray, lost, in the digital forest of ignorance and animosity.” In the essay, Krause takes up the defense of the poet’s maligned name online: the ridicule that Dante invented hell of his own accord and the poor biblical education that proliferates across social media. Why, then, read Dante and the Inferno if it is so misunderstood and out of time? Krause posits that it is because Dante, through his journey, teaches us to pity the damned and find our own salvation within that experience.

Krause continues to explain that Dante is an exile—actually, spiritually, and poetically. His epic opens with his misaligned heart, one pursuing false loves. Krause goes forth to dissect the first layers of hell and Virgil’s relationship to Dante. It is through his, Virgil’s, guidance that Dante learns to embody forgiveness and compassion for sinners, in fact for everyone. Continuing to play upon the theme of ultimate Love, Krause concludes that “If we cannot love and cannot forgive then we really will entrap ourselves in hell, for hell is a loveless place created by the pride, passion, and deceit of the self which reign supreme at the expense of all others.” It is through learning to love, Krause compellingly argues, that we may escape our self-made hells, jokingly even for those who misinterpret Dante.

“Dante and the Digital Inferno” brilliantly situates Dante within the disorienting landscape of modern digital life. By comparing the social media “forest of ignorance and animosity” to Dante’s inferno, Krause highlights how timeless human struggles—pride, deception, and the difficulty of moral discernment—are amplified in our contemporary, hyperconnected world. The essay suggests that Dante’s guidance toward compassion and forgiveness remains urgently relevant: even in the swirl of online misinterpretation and hostility, the cultivation of love and moral clarity can rescue us from the self-made hells of modernity. In this way, Krause draws a compelling line from the medieval poet’s vision to our present digital condition, showing how the spiritual and literary imagination can illuminate contemporary cultural challenges.

The final poem, “The Night of Christ’s Nativity,” epitomizes Krause’s point that all poetry, all written word, is oriented to the embodiment of Love, Christ himself. It leaves the reader, through the point of view of the wisemen, with the proclamation that:

The star you see which captures your gaze You will follow for nights and days Till you find, in a mountain cave, The newborn king who will become a slave And save the world and your soul Whom you and the nations shall extol

These ultimate lines are a bookend to Krause’s introduction, that “every great monument that enchants the soul has love at its heart and can move the heart to the Good, True, and Beautiful.” Krause thus offers not only an anthology of verse but also a manifesto for the renewal of culture through poetry. His conviction that all true poetry orients the soul toward Love gives the collection both coherence and urgency. While some may find his sweeping claims idealistic, the fusion of history, theology, and personal verse makes the work a serious contribution to the ongoing conversation about the place of the arts in contemporary life. At its best, Krause’s writing reminds us that poetry is not a luxury but a vital mode of human knowing, one that can re-enchant our disenchanted age and direct us once again toward the Good, the True, and the Beautiful.