“The Art of the Commonplace: Wendell Berry’s Vision for a Grounded Life.” Starting next week, Dr. Jeremy Cowan is leading an online course that will discuss some of Berry’s seminal essays: “Wendell Berry’s The Art of the Commonplace calls readers to live with greater intention—rooted in place, connected to one another, and attentive to the land that sustains us. Over four weeks, this discussion series will explore eight of Berry’s most resonant essays, pairing his reflections on home, work, and faith with conversation about how these ideas might take shape in our own lives.”

“How I Became a Populist.” In a searing essay, Alvaro M. Bedoya, a former FTC commissioner, describes how he came to embrace populism: “If you focus on the conflict between left and right, if the most important thing is what you are—your party, your state, your race, your ethnicity—the people I met could not be more different. On the one hand, you have rural, white small-business owners, generations into building a life in this country. On the other, you have urban Latino, Haitian, African, and South Asian immigrants, every one of them a worker. The line between them is sharp, almost tribal. What could they possibly have in common? Everything—if you look at what they need. The people I met as a commissioner may look different, but what they need is surprisingly the same: They need a government that gives them a level playing field against the powerful and wealthy. They need the courts to check corporations when they abuse that power and wealth. They need basic dignity and control in their material lives.”

“Elites’ Long War Against the ‘Deplorables.'” Mary Eberstadt remembers Christopher Lasch’s prophetic warning against elite failures: “Ironically, as Lasch did not live to witness, the revolt of the elites is now eclipsed because the masses have come to return the favor. The resurgence of national feeling and populist revolt shouldn’t have come as a surprise, let alone as the existential shock that so many affrighted pundits have professed. It is a natural political reaction to what the social critic from Rochester identified early on: the vacuum of empathy and accountability at the top.” (Recommended by Bill Kauffman.)

“I’m a Proud Luddite.” Grant Martsolf defends Luddites from the slurs of the techno-utopians: “I have come to the conclusion that the smartphone is terribly anti-human. I see it as a device of endless distraction that places a prostitute in my pocket while spying on me and my family in order to sell us piles of cheap stuff we do not need and should not want. I have no interest in that. I also have no interest in looking across the table at my teenagers during family dinner to find them cackling slack-jawed at empty-headed nonsense videos that keep them from reading, praying, and paying attention to their baby sister. Yet somehow, because I refuse a smartphone, I am supposed to be a backwards Luddite.”

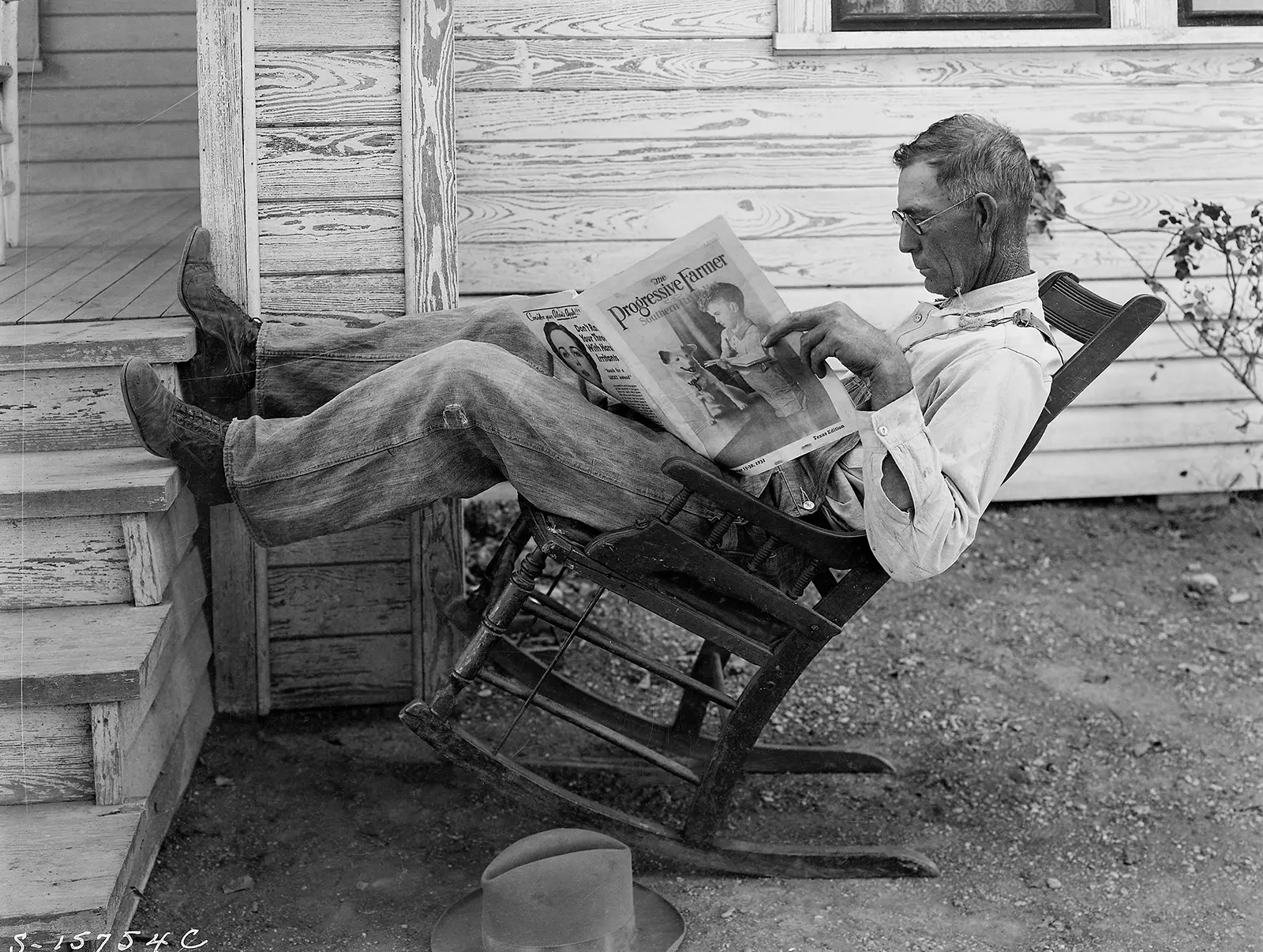

“To Read, or Not to Read?” LuElla D’Amico considers why Americans, like our current president, aspire to read but don’t actually spend time doing so: “Lincoln, Bush, and Obama carved time from their busy schedules—even presidential ones—to read. Trump, like many citizens today, says he loves reading but admits he does so only when he ‘gets the chance,’ which seems to occur more in theory than in practice. Indeed, according to a 2025 NPR/Ipsos poll, while 82 percent of Americans believe reading is a valuable way to learn about the world and nearly all parents (98 percent) want their children to develop a love of reading, only about half of Americans (51 percent) have read a book in the past month.”

“Postliberalism’s Reluctant Godfather.” I missed this fine essay when it came out this spring, so I’m linking to it now. Nathan Pinkoski offers a deft survey of Alasdair MacIntyre’s intellectual career and his unexpected legacy: “It is impossible to understand the new postliberal right without discussing Alasdair MacIntyre. There is, to be sure, considerable theoretical distance between MacIntyre himself and these postliberals. MacIntyre himself also tried to put as much personal distance between him and those rightists as he could, such as in his pronounced refusal to read Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option. In short, MacIntyre begat devoted children that he disowned.”

“Wild Oysters Make a Comeback in Maine.” Kirsten Lie-Nielsen tells the story of oysters returning to a warming Maine coast: “Jacqueline Clarke points out that while wild oysters have been missing from the Maine coast for many decades, they have been part of the state’s coastline longer than they’ve been absent. ‘They’ve been around for thousands upon thousands of years, everywhere, up and down the coast, and definitely in the Damariscotta,’ she says. To forage or eat a wild oyster along the mineral-rich waters of the Damariscotta is to bridge the centuries, to connect Maine’s ancient past with its present. In that sense, the new population is not just a harbinger of change, but a symbol of resilience.”

“Heather Cox Richardson’s Revisionist History.” I remain fascinated by the ways that influencers can build large audiences outside traditional institutional structures, audiences who are apparently hungry for someone to feed them simplistic, conspiratorial narratives. Blake Dodge and Katherine Dee report on one of the most popular Substackers: “Heather Cox Richardson may not be a household name, but she’s one of the most influential voices in American media. From her home in Maine, the Boston College professor has built a following of 2.7 million subscribers—that’s 1 million more people than Jimmy Kimmel’s average audience size, and just shy of the left-wing political commentator Hasan Piker’s 3 million streaming followers—who treat reading her nightly Substack, Letters from an American, as an act of patriotism. To her followers, Richardson is the last responsible adult in the room: calm, authoritative, devoted to the hard facts of history. She presents herself as America’s professor, neither a polemicist nor performer. Yet the history in her telling is never neutral. Each night, she offers a morality tale in which Republicans play the villains; Democrats, the weary defenders of reason.”

“How Higher Ed Should Engage with the Government.” For another perspective on why it’s important to rightly identify America’s root problems right now, see this from Danielle Allen: “What’s at stake in a judgment as to whether [America’s gravest danger] is authoritarianism or corruption? It’s crucial that we correctly define the fundamental challenge we face. . . . If we follow this path — if we strive to replace corrupt processes with constitutional ones — we will make clear that we are using every power at our disposal to strip our national institutions, and our own institutions, of corruption. That is the only way to steady this storm-tossed ship.” (Recommended by Adam Smith.)

“Should Universities Educate Students?” And speaking of higher ed, Scott Samuelson casts a Swiftian vision for academic institutions: “Universities should attract students with what they really want: concerts, sporting events, gaming stations, food courts, swanky dorms, fewer requirements, and so on. (At the same time, it’s savvy to put fees on some of these goods to generate more revenue for the university.) But the university shouldn’t just be an expensive four-year resort experience. There needs to be a value-add that justifies public support and the increasing cost of tuition and room and board. The ostensible value of the university needs to involve credentialing students for successful entrance into the economy.” (Recommended by Scott Newstock.)

“The Post-Literate Republic.” Adam Smith considers what post-literate politics might look like: “The end of literacy does not necessarily change minds or introduce new ideas, though we are certainly living through a period of ideological ferment and factional realignment. What it changes is not what people think but how they think it, how they come to think it, and how they communicate it to others. A post-literate America is one in which politics is made by people whose attention is not sustained by reading books but fractured by consuming bite-sized bits of infotainment, whose arguments are not disciplined by the expectation that they make logical sense but are simply accepted or rejected according to their marks of tribal identity, and whose communication style is neither calm nor impersonal but hectic and “authentic,” a style that aims not to persuade but to go viral.”