The following is a talk given at the annual conference of The Academy of Philosophy and Letters on June 16, 2012 in Baltimore, MD.

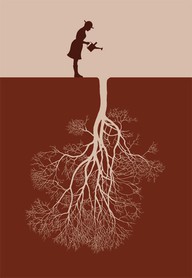

In her book The Need for Roots, French writer Simone Weil states that “to be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul. It is one of the hardest to define. A human being has roots by virtue of his real, active and natural participation in the life of a community which preserves in living shape certain particular treasures of the past and certain particular expectations for the future.” If this is the case, then a society characterized in large part by its restless mobility would be ill-equipped to provide one of the central human needs.

According to Weil, modern rootlessness is not merely geographical or even cultural but spiritual as well. Writing of mid-twentieth-century France, but sounding as if she could be writing to twenty-first-century Americans, she describes “a culture very strongly directed towards and influenced by technical science, very strongly tinged with pragmatism, extremely broken up by specialization, entirely deprived both of contact with this world and, at the same time, of any window opening to the world beyond.” This suggests that humans have a need for physical or geographical roots in a particular place embodying particular traditions, habits, and practices. But equally, humans require roots in a transcendent world, a world of spirit, a world of moral truth. In short, the uprootedness of many today is both spiritual as well as geographic.

Spiritual rootedness is a significant challenge where secularism has been steadily advancing for several centuries. For the Medieval mind, all of creation was connected in a great chain of being that extended from the highest creatures, the angels, down to the lowest, most insignificant atom. Humans, created “a little lower than the angels,” had a distinct place in the order of creation. All things were arranged in a hierarchical fashion with the infinite and eternal God presiding over all. This vertical chain unified all of reality under the authority of God, but it also provided a means by which all classes of things could be properly categorized as distinct from all other classes of entities. Thus, both unity and diversity were captured in this conception of reality. According to this vision of reality, humans belong to the creation but, because they are the highest of the embodied creatures, they are also tasked with ruling the rest of the physical creation. Thus, humans had a clear place in the order of reality, and they had a clear responsibility that accompanied their privileged position.

With the collapse of the medieval world, the great chain of being slowly crumbled as well. The order of reality was lost to the imagination and the hierarchical arrangement was replaced by a flattened conception of reality. No longer did all parts of creation have their neatly assigned places in the created order. In the process, humans lost sight of their clearly delineated privileges as well as their responsibilities. Set adrift on the tides of a seemingly limitless universe, the sense of place that existed in the medieval world was exchanged for alienation and uncertainty. Yet, the longing for a place remained intact. Modern restlessness is, at least in part, the product of a world where the chain joining all things has been severed and each person finds himself striving to find his own place in a seemingly dis-integrated world.

Skepticism about transcendent reality tends to lead in the direction of philosophical materialism, and philosophical materialism in our age has opened the door to the more general materialism of consumerism. After all, if we are merely pleasure-seeking creatures who cease to exist with the demise of our physical bodies, then our chief concern will be the enhancement of our personal pleasure, and, to be sure, personal pleasure is greatly enhanced, if only temporarily, by the things money can secure. When members of a society make material gain their central concern, that society will embrace an ethic of mobility, for each person will be quite willing to relocate in pursuit of affluence. Thus, we see “communities” of transient individuals each committed primarily to the acquisition of material gain and the betterment of their immediate family members. Home tends to become merely a launching place for economic and hedonistic endeavors, and individuals tend to lose any abiding concern for the long-term future of the local community. In such a setting, any notion of community membership, which evokes ideas of commitment and loving concern over a lifetime, is replaced by the much narrower concerns for personal affluence and individual pleasure.

Skepticism not only undermines commitment to a geographic place, it also eliminates any idea of a heavenly home, which can serve to moderate and even redirect the sort of consumerist passions engendered by modern society. Thus, it seems that the same set of beliefs that create geographic homelessness also create a spiritual homelessness as well. Too many people today find themselves without a place either in this world or the next.

In contrast, a healthy local community comprises particular people inhabiting a particular place and sharing local customs, activities, and stories. In short, they participate in a complex web of relations that are flavored by the particular history, geography, and culture of that place. When we describe a local community in those terms, it becomes clear how a massive national community is simply an impossible ideal. Even more fanciful is the notion of a world community. To be sure, because we share a common nature and many common needs and desires, we can empathize with and render aid to humans from radically different communities. But the cosmopolitan ideal that one can be a “citizen of the world” is only imaginable if we strip down the rich notion of community to mean something like “the brotherhood of man.” The idea of universal brotherhood is appealing and, as far as it goes, it is true, but abstract brotherhood is not the same as living in a local community with men and women of flesh and blood. Local communities include, along with the images of pleasant hominess, the rude woman at the market, the town drunk, and the idiosyncratic recluse who lives at the end of the lane. Ivan Karamazov, in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, gets at this distinction when he declares that he loves humanity but hates human beings. Oddly enough, it may be easier to love the world than to love our neighbor. Ultimately, when love for a particular place and the people inhabiting that place are lost, community is lost as well. Love itself becomes an abstraction.

The loss of commitment to a particular place results, at least in part, in the restless mobility that characterizes so much of American life. And even when particular individuals stay put in one place, the very possibility of easy mobility makes it possible for people to inhabit the world of the potential future rather than the concrete present: “I must keep my options open” means, in practice, refraining from committing to any particular place. Of course, potential communities are far more desirable than actual ones. We can always imagine a place better than our present one. Holding out for the perfect situation is, in some ways, easier than getting involved in the conflicts and irritants that inevitably exist in reality. But though the temptation to stay at arm’s length, to inhabit a place with ironic detachment, is alluring, the implications for a robust and healthy local community are grave. Indeed, if a critical mass of such people occupy a certain place, they are merely a collection of individuals rather than a community. They are mere residents and not stewards. In such a situation, local stories and traditions that are only kept alive in the telling and the practice are lost. But these are the very things that provide context and meaning to our social lives. They provide us with guidelines for acting together. They are the source of manners and customs that make life in a community possible. With the loss of common traditions and shared stories, we lose the cues that help us navigate a particular local world.

In the end, where commitment is feared and deracination is seen as a virtue, living contentedly in one place is a counter-cultural act. It is an act born of gratitude, for it recognizes the subtle and simple gifts native to a place, many of which are visible only to those who love the place and are committed to its future. Grateful creatures, living together through time will necessarily be mindful, perhaps only intuitively, of the kind of scale that is necessary to both enjoy the gifts inherent in a place and care for those gifts in a way that preserves them. Contentment is the offspring of humility, for humility seeks not to dominate or exploit but to steward good things well. The practical result is lives constituted by propriety, where the human world of artifacts and relationships complements the geography, flora, and fauna of the natural world. Lives constituted by propriety are lives well lived in the context of a particular place, lives where harmony, not dissonance, is evident in the wisdom and affection that characterize the actions of individuals.

Wendell Berry—a farmer and a writer—understands the intimate connection between rootedness and a properly framed human life. Unlike those who use the term “community” rather loosely to refer to anything from a collection of houses situated in the same suburban development to the grossly abstract notion of a global community, Berry argues that a meaningful community must include the ideas of rootedness and human scale. “By community, I mean the commonwealth and common interests, commonly understood, of people living together in a place and wishing to continue to do so. To put it another way, community is a locally understood interdependence of local people, local culture, local economy, and local nature.” Berry identifies the corrosion of flourishing communities as the result of an excessive individualism that places rights ahead of responsibilities and economic gain ahead of meaningful and durable relationships—relationships with neighbors, with local customs and practices, with the land itself. As he puts it, “if the word community is to mean or amount to anything, it must refer to a place (in its natural integrity) and its people. It must refer to a placed people….The modern industrial urban centers are ‘pluralistic’ because they are full of refugees from destroyed communities, destroyed community economies, disintegrated local cultures, and ruined local ecosystems.” Ultimately, according to Berry, “a plurality of communities would require not egalitarianism and tolerance but knowledge, an understanding of the necessity of local differences, and respect. Respect, I think, always implies imagination—the ability to see one another, across our inevitable differences, as living souls.”

For Berry, community requires commitment to a particular place and the people, culture, economy, and ecology of that place. At the same time this localism is not tribalism, for it ultimately requires that people recognize other persons, whether members of one’s community or not, as living souls, biological creatures but much more: creatures who exist as members of both a physical world and the world of spirit, creatures capable of labor, of love, and ultimately of worship.

15 comments

D.W. Sabin

Not enough people plant anything……the urban population thinks it can simply shop to survive. Planting, particularly this year concentrates the mind. It leaves the mind little amused by the prevailing lies. Humans, it would seem, favor treachery over the more tame amusements of cooperation. But , it has always been thus. Review the history of Jerusalem should you doubt it. The environment and humanity would seem to be a couple of barfly drunks at last call. It would not be so depressing had humanity not held so much potential to love this thing we call the environment, instead of treating it to but another drunken debauch.

Mike Sims

The problem with this topic is the lack of a single word that captures the idea of “a complex web of relations that are flavored by the particular history, geography, and culture of place.” People cannot have a conversation about it because we cannot succinctly describe it. I’ve started using the word nanocivics because, like the word nanotechnology, it reminds people that something amazing is possible at the small-scale that is otherwise impossible. Just do a search for nanocivics, you’ll see what I mean. The Germans are great at this, we need nanocivics to be the current American zietgeist.

T. Chan

Amazona, the obstacles to the creation of community are formidable in many places, but one can still do what one can, at least with one’s family. Building up one’s extended family or clan would be a start, with a focus on the practical skills that are needed in the future, maybe even with an eye on eventual mass resettlement elsewhere.

amazona

This is all well and good. Everyone wants community but the barriers are real not just the choices of individuals. The piece appears to recommend individual decisions to stay in place for the sake of a community. You can literally stay in one place but the social, physical and economic structures of the modern city (where most of us live and will continue to live) are built to keep people apart. One person or even a group of committed persons can not overcome these obstacles. I have lived in one house for 22 years and I have seen many people come and go on our street. Staying put has not created community. The vision of an idillic past is romantic and unproductive. Those who defend the hierarchy of the past usually like to sidestep the basis (race, gender, wealth, intellect?) and forget that men love to lord over others- call it original sin if you must. How we are to remake the world we have inherited? It is about the structures that shape our lives not just our choices.

David Smith

Mr. Peters, you once again hit the nail on the head. Until we again place God in His rightful position as Pole Star, from and around which all our human activities and purposes revolve, we are only playing at Babel . . . yet again. What’s the old Hamilton Camp song? “O God, the pride of man, broken in the dust again!” What’s our purpose? What are our blessed limitations? Without these we might as well be fish out of water or trains without tracks!

T. Chan

” I placed medieval communities in quotations to acknowledge that the inherent injustice of medieval power structures give the lie to any idea of such communities fulfilling some sort ideal standard. ”

Inherently unjust, how so? Because they were not modern liberal democracies? Given the plurality of political forms in medieval Europe such a generalization regarding medieval communities might best be avoided. The temptation to power is a great one for fallen man — I believe it makes for a better understanding of human history and the growth of the state than standard reactionary intellectual history and its blaming of liberalism. Nonetheless, the existence of a strong central political power over all of a national region, much less all of Europe, was only a dream during much of the medieval period.

robert m. peters

Evil has been present in man since the fall and will remain his companion until all things are fulfilled; however, Providence in His mercy has mitigated evil with community and commonwealth, with competing and overlapping authorities, and with individuals integrated into those communities and commonwealths. One of the aspects of Modernity is that through the dual abstractions of the autonomous individual and of the Hobbesian state, an abstract corporation with a monopoly on coercion and with the ability to define the limits of its own power Modernity has set about and out to level the mitigating institutions, replacing true community with the collective. Also, Modernity is marked by unbelief, not just unbelief as it relates to the Christian faith, but unbelief that man is a creature in a created order whatever the nature of the Creator.

The only legitimate ideal is the coming Kingdom of God, the Republic of republics; however, when we live creaturely, i.e. without unbelief, and when we live Christianly, i.e. with faith in Christ, knowing our limitations and accepting them, i.e. living in community, we best foreshadow and become the point of the spear of the coming Kingdom. That is why community is so important; and that is why, in the era of unbelief, community is so rare and precious and needs to be nurtured.

Tim

I can certainly see the merit in defending the Medieval Period from those who would portray it as a lost era. My point is more to demonstrate that, although the medieval world does not represent a dark era in the world’s history, we should also be careful not to remember it as the halcyon days which predated the evils of modernity. Medieval living is not the antidote to modern exitenstial struggles. I placed medieval communities in quotations to acknowledge that the inherent injustice of medieval power structures give the lie to any idea of such communities fulfilling some sort ideal standard. Indeed, both modern and medieval communities fall far short of this ideal, but for different reasons, hence, labeling them as such is somewhat misleading.

Rob G

In his book Standing by Words Berry has himself written of the inescapability of hierarchy, that it is natural and an aspect of the created order, and thus both necessary and good. The error of modernity, he states, is to reject the notion of hierarchy per se because of the existence of unjust hierarchies. The real problem, according to Berry, lies not in hierarchy but in injustice.

robert m. peters

Tim,

All true communities within the created order – including those of ants, bees, wolves and men – are communities based on hierarchies, those hierarchies varying in nature and design from created community to created community. One is not sure why you placed medieval communities in parenthesis, their being no less valid as communities than any other. Some communities within the thousand or more years which we have very erroneously labeled “the Middle Ages,” thereby betraying the very “progressive” liberal arrogance of our own Modernity, implying there is enlightened “Antiquity” and enlightened “Modernity” with all of that dark stuff in between, were quite flexible and some more ridged. No community of the Middle Ages functioned autonomously. Medieval communities, with all of their variations and diversity, flourished in the framework of the classical Christian tradition and the informing, in the denotative sense of that word, authority of the Church. A close reading of Simone Weil and her late apologist A. J. Conyers reveals that the eternal is always revealed in the particular, i.e. there is an inextricable link between the two, so that the truly transcendent is to be found in the local and in the sense of place. Conyers points out that the difference between a pilgrim and a wanderer is that a pilgrim has a sense of place from which he is called to another place by that Voice of Voices operating in an through the created order. The wanderer has no sense of place and no sense of calling. I do indeed agree with you that reality deserves more consideration.l

Tim

Many important insights here, but I wonder about the implied relationship between Berry’s idea of community and that of Medieval Europe. One of the most fundamental aspects of medieval “communities,” to the extent that they can be labeled as such, is that their human relationships were also built on established hierarchies. The rigid structures of that particular way of living do not reflect the sort of cooperative pursuit of living well embodied by the Port William membership. Furthermore, we should be careful not to assume that communities may achieve autonomy anymore than persons. It is a vain myth that any community can function autonomously, separate from the world in which it is situated. Not even medieval communities existed apart from complex transnational networks, commercial and otherwise. This reality deserves more consideration.

DOD

It may be paradoxical to affirm the abiding importance of actual, particular, local community via the com boxe of a blog on the internet. Where, however, except in the alchemy of Weil’s “roots” and real community can we learn the truth and use of such paradox. An essay well said and true. Thank you.

David Smith

“In the end, where commitment is feared and deracination is seen as a virtue, living contentedly in one place is a counter-cultural act.”

And so we mindlessly and frantically labor for the next thrill, the next titillating and heart-rending drama as seen on “news” channels that occurs half a continent away, while ignoring our neighbors next door. I have often thought this post-modern obsession with “extreme” sports a substitute for living vitally in the present; the quest for connectedness via local tragedies as seen on tv, mere emotional pornography.

You correctly go to the heart of the spiritual malaise that besets our society. I’m sure as you know, well-written words from you or Mr. Berry aren’t enough; too many people today regard this as a foreign language. However, the “counter-cultural” act of living out community will hopefully call folks back to their proper relationships with God, each other, and the earth they are supposed to be connected with.

Thank you!

Comments are closed.