About this time last year, Mitch Daniels, the Republican Governor of Indiana, stirred some controversy by calling on conservatives to declare a truce on so-called “social issues” so that they might concentrate their political energies on seemingly more pressing matters such as federal deficit reduction. At the time, many political commentators considered these statements as an effort on the part of Daniels to position himself as a national leader of his party in preparation for a 2012 presidential bid. Still, Daniels’s sense that social issues—abortion and gay marriage in particular—were distracting conservatives from their primary duty to keep government fiscally responsible speaks to a long standing tension present at the birth of the modern conservative movement in the 1950s. That tension, in a nutshell, has been between the libertarian and traditionalist wings of the movement. Libertarians understand conservatism as fundamentally a philosophy of individual freedom, particularly freedom from government constraint in matters economic. Traditionalists understand conservatism as primarily a defense of the values that have historically shaped Western civilization; traditionalists embrace some conception of liberty as one of those values, yet tend to subordinate negative liberty (freedom from constraint) to more positive, substantive values that they generally referred to as virtues. So, to take a hot-button “social issue” like abortion: the libertarian is content that government does not impose abortion on individuals, while a traditionalist would insist on prohibiting abortion in order to foster what George W. Bush, echoing Pope John Paul II, called a “culture of life.”

The locus classicus for this debate in early conservatism is L. Brent Bozell’s 1962 National Review article, “Freedom or Virtue.” Bozell is one of the most significant intellectuals of the early postwar conservatism, though largely forgotten today. By the late-1960s he had largely recused himself from the movement, yet his departure has received scant attention in mainstream histories of conservatism. Bozell left because he could no longer reconcile his commitment to traditional values—in his case, traditional Catholicism—with the libertarian freedom that seemed to steer the conservative movement as a whole. Bozell never saw freedom and virtue as mutually exclusive, but instead argued that conservatives needed to see them as hierarchically ordered, with virtue as the base, guide, and end of freedom, rather than simply a choice exercised (or not) by free individuals. His intellectual career raises troubling issues for those who would link modern conceptions of negative liberty to some notion of tradition.

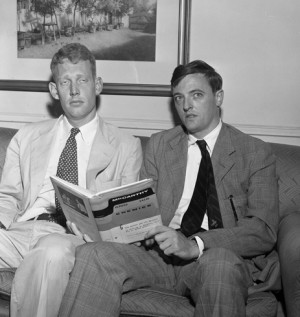

As Bozell is largely a forgotten figure, I would like to start with a little biographical background. He was born 1926 in Omaha, Nebraska. Bozell converted to Catholicism while attending Creighton Preparatory School, the high school connected with Omaha’s Jesuit-run Creighton University. He served in the Merchant Marines during WWII and after the war attended Yale University. At Yale, he met an aspiring young conservative Catholic intellectual, William F. Buckley. In Buckley, Bozell found a kindred spirit. The two quickly proved to be champion debaters and defenders of political conservatism at an institution known for political liberalism. Buckley would make his first national splash as the author of God and Man at Yale (1951), a scathing expose of what he saw as the rampant secularism of the Yale professoriate.

If Buckley’s defense of Christianity—or at the very least, some generic, deistic “god”—gave him a footing in what would become the traditionalist wing of the conservative movement, we should recall that his book could just have easily been titled “The State and Man at Yale.” His first chapter exposes the Yale professoriate’s attack on Christianity, but his second chapter addresses his teachers’ attack on individualism and their promotion of statist collectivism. With a consistent tone of moral outrage across these chapters, Buckley gives divine, Christian sanction to an economic individualism that rose to dominance in the nineteenth century at the very time in which Christianity was losing its public standing in the West. Here we see an early instance of an effort to link libertarianism and traditionalism.

The two orientations would not, however, stick together by their own power. They needed some external bonding glue and found it in the third strain of American conservatism, anticommunism. After graduation from Yale, Bozell and Buckley went to work for the most controversial conservative anticommunist in American politics, Senator Joseph McCarthy. McCarthy made headlines by making unsubstantiated accusations of domestic subversion by Soviet communist agents at every level of American government and society. In 1954, he finally fell from political grace after accusing the U.S. Army of harboring communists. Bozell and Buckley (now his brother-in-law) remained committed to the cause and published a defense of McCarthy entitled McCarthy and His Enemies. The two argued that although McCarthy’s tactics might have been extreme, his cause was just, and his enemies seemed willing to let the government be overrun by communist spies.

Bozell, like many conservatives, saw the Cold War as nothing less than an all out battle between good and evil, a battle for the survival of Western civilization. Many liberals saw it the same way, but differed from Bozell and other traditionalist conservatives in their understanding of Western civilization. So-called “consensus” liberals understood Western civilization through the lens of the philosopher John Locke; for them, Western civilization meant the development of respect for individual rights and tolerance of religious and cultural diversity. Against Locke, traditionalists invoked Edmund Burke, the British/Irish critic of the French Revolution, who saw the insistence of the primacy of individual rights as a threat to family, religion, and indeed all that was sacred in traditional society. Burke attacked the whole social contract tradition—the thought of John Locke as well as Jean Jacques Rousseau—for its misunderstanding of society as being created through the consent of individuals. He argued that society was by nature organic, not contractual; the product of centuries of natural growth yet having no clear point of origin in consent. For Burke, social relations were an extension of family relations; just as you cannot choose your relatives, so you cannot create society.

Traditionalist conservatives had a hard time conveying these ideas to a popular audience. It was one thing to inveigh against godless Communism abroad; it was another to convince Americans of the danger of godless liberalism at home. Outside of elite institutions such as Yale, America in the 1950s seemed like a very godly nation. In 1955, the sociologist Will Herberg highlighted the specifically religious dimension of the liberal consensus with his classic Protestant, Catholic, Jew. Americans shared not only the Lockean values of individual rights, but also a common Judeo-Christian religious tradition. If Herberg was distressed by the superficiality of American religiosity, most Americans seemed content with Eisenhower’s famous quip, “our government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.” Agnostic liberal intellectuals like Arthur Schlesinger, Jr. thought religion good for democracy; liberals and conservatives alike participated in the baby boom, with suburban domesticity perhaps the real religion of 1950s America.

Despite the generally religion friendly climate of public discourse in the 1950s, religion and tradition proved to be divisive issues in the early years of the conservative movement. Bozell and other conservatives staked out their claim to leadership not on their credentials as defenders of tradition, but on a strident anticommunism and an uncompromising commitment to free market economics against the legacy of New Deal liberalism. William Buckley had made a name for himself first of all by attacking liberal secularism, and his National Review provided space for traditionalists to air their particular understanding of conservatism. Whittaker Chambers, whose Witness was something like the bible of conservative anticommunism, viewed the radical libertarianism of Ayn Rand, with its reduction of social and political life to the will to power, as the moral equivalent of totalitarian communism itself. At the other end of the spectrum, Max Eastman, a Marxist-turned-strident (but secular)-anti-Communist, resigned from the editorial board of the National Review in the early 1960s because of the magazine’s openness to traditional religious perspectives. The debate between libertarians and traditionalists was constant and often bitter with each group more than willing to write the other out of the movement. In the early 1960s, Frank Meyer, a former Marxist, secular libertarian and founding board member of the National Review, devised a strategy for reconciliation he dubbed “fusionism.” Meyer maintained that freedom was the ultimate goal of politics and that the state should have no say in promoting individual virtue or any substantive values. Freedom is, in a sense, the primary virtue, and end in itself; nonetheless, it also serves as a means to achieve any other virtuous end an individual may desire. Meyer allowed that conservatives could, and perhaps should, make full use of their individual freedom to promote virtue in the private sphere, but should never seek to marshal government power to enforce particular moral values on other free individuals.

Bozell’s 1962 essay, “Freedom or Virtue?,” remains the most powerful traditionalist response to Meyer’s fusionism. In essence, the question Bozell poses in his title demands a choice not of values, but of priorities. For Meyer and his fellow libertarians, freedom comes first and our actions are “virtuous” only to the degree in which we freely choose them. Speaking for traditionalists, Bozell concedes that freedom is essential to virtue, but insists it is not the primary or ultimate value. Freedom has value or meaning only in terms of the objects or ends that it serves. No minor debating point, the question of priority has profound implications for one’s vision of a just and free society.

Bozell illustrates this philosophical distinction with the example of divorce. He posits the case of two men, one an American (Mr. X), one a Spaniard (Mr. Y), both of whom are dissatisfied with their marriages. In America, divorce laws are comparatively lenient and there are possibilities for remarriage. Mr. X moves in fairly liberal social circles and divorce would carry no stigma from his friends and business associates. Still, at the end of the day, he decides against divorce because he feels it is wrong. The case of Mr. Y, the Spaniard, is very different. Spain does not permit divorce. Mr. Y could possibly travel to France to get a divorce, yet this would be expensive. Upon returning to Spain, he would face tremendous social ostracism and have little or no chance for re-marriage. In the end, Mr. Y decides to remain married. Bozell concedes that between these two men, most of us would consider the American Mr. X more virtuous: he could have gotten a divorce but did not as a matter of personal virtue.

Bozell then he draws a disturbing inference from this judgment:

And it follows—does it not?—that if we are seriously interested in maximizing opportunities for virtue, something will have to be done about Spain. Her laws, traditions, customs interfere with freedom. They are ‘crutches’—kick them away. And in the United States, conditions are not entirely satisfactory either. We will want to make our own divorce laws even laxer. We will also want to launch a public education campaign (privately endowed of course) aimed at breaking down residual social prejudices; and perhaps, to overcome the mechanical difficulties, a special fund could be set aside for periodic newspaper notices advising dissatisfied spouses of the most convenient cut-rate agency or mail order house. We will do our best, in other words, to reduce the ‘constraints’ of ‘superior power,’ confident that if Mr. X can stick by his guns under these conditions, he will really be virtuous. It is not that we favor divorce, mind you; it is just that we want virtuous men.

What Bozell presents as satire reads today as prophecy. Those who at the time might have argued Bozell was being unfair and taking libertarian principles to an illogical extreme would live to see the divorce scenario he extrapolated from libertarian principles become the law of the land in America. History has borne out the traditionalist understanding that law is normative, not neutral; it reflects and promotes certain values against others.

Still, in defending the permanence of marriage against divorce, Bozell was no precursor to “family-values” conservatism or the Christian Right. Aside from the fact that no Christian conservative today talks seriously about outlawing divorce, Bozell’s critique goes much deeper than anything we hear from so-called cultural conservatives today. Divorce was simply one example of a broader misunderstanding of freedom as freedom from constraint. In affirming virtue, Bozell refused to reduce it to a set of moral constraints, such as the prohibitions of the Ten Commandments. He pulled no punches and concluded his essay by invoking the Christian notion that to save your life, you must first lose it. Bozell charged that the urge to freedom for its own sake is a rejection of God and nature: “true sanctity is achieved only when man loses his freedom—when he is freed of the temptation to displease God.” Stated positively and substantively, man is only free when he acts in such a way as to please God. This is positive liberty, with a Christian vengeance.

Though one could easily read Bozell’s essay as an ultimatum to libertarians, it did not succeed in breaking the back of fusionism. Practical politics and the transcendent principle of anticommunism continued to hold the fledgling conservative coalition together. Defeat notwithstanding, Barry Goldwater’s 1964 presidential campaign marked a turning point in conservative political mobilization, one that would bear fruit sixteen years later with the election of Ronald Reagan. Liberal outrages against the conservative vision of America only intensified during the mid-sixties and provided at the very least the common bond of a common enemy. As the streets exploded in waves of riots, liberal judges saw fit to extend the spirit of the Civil Rights movement to criminals, granting them protections and immunities conservatives were convinced only exacerbated the lawlessness of the times. These developments helped Bozell to maintain a connection to mainstream conservatism at a safe remove from the contentious issues of fusionism. In 1966, he published The Warren Revolution, one of the most systematic and influential conservative critiques of liberal judicial activism. Bozell accused Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren of betraying the Founding Fathers and the original intent of the Constitution in order to advance a liberal social agenda (a critique that remains central to American conservatism).

Still, The Warren Revolution was in many ways Bozell’s last positive contribution to mainstream conservatism. Bozell may have been able to wax patriotic about the Founding Fathers, but he had for quite some time found America itself all but uninhabitable. Since 1961, he had been spending a good deal of time living as a kind of cultural exile with his wife and children in Spain. For Bozell, the Spain of Francisco Franco offered a rich, organic Catholic culture that embodied all the principles of the traditionalism he had argued for against Meyer and the fusionists. Such organic unity had to a large degree once characterized urban, ethnic, ghetto Catholicism in America, but the twin ruptures of suburbanization and the Second Vatican Council undermined the ability of the Church to stand as any kind of united traditionalist front in liberal America.

Bozell found himself increasingly at odds even with the self-styled conservative Catholics at the National Review. When his brother-in-law William Buckley endorsed abortion as a legitimate legal option for non-Catholics and provided a platform for Catholics to speak out in favor of contraception, Bozell and a group of like-minded Catholic traditionalists broke with the National Review to found a new journal, Triumph. Though still in dialog with American conservatism, Triumph drew its intellectual bearings from the traditionalist Catholic culture of Franco’s Spain. The relationship between the two journals was at first cordial. Explicitly Catholic, Triumph devoted a lot of space to decrying the liberalization of the Catholic Church, especially in America. Buckley welcomed Triumph as an antidote to liberal Catholic journals such as Commonweal and America; of course, since theological liberals tended to be political liberals, Triumph’s screeds had a certain political usefulness.

All this changed in the late 1960s. The Vietnam War broke the last solid link between Bozell and mainstream conservatism. Anticommunism no longer covered a multitude of sins. At its founding, Triumph was still well within the anticommunist consensus. Vietnam disabused Bozell of his illusion that the fight against communism was always and everywhere a fight for God. Though he would never endorse Ho Chi Minh or embrace communism, Bozell came to see American intervention in Vietnam as an unjust war. Perhaps even more provocatively, the man who in 1966 attacked the Warren Court for coddling criminals had by the end of the decade come to defend black riots in American cities as a protest against capitalism and materialism.

Still, no issue set Bozell against America more than abortion. If Bozell’s views on war and capitalism seemed to place him at the left end of the political spectrum of the time, his opposition to abortion left no doubt that he had moved well beyond the conventional spectrum of American politics. For Bozell, the growing acceptance of abortion in the late 1960s convinced him that America lack the moral, religious and cultural resources to save itself. In two 1968 Triumph essays, “The Death of the Constitution” and “The Autumn of Our Country,” he renounced his earlier argument that the disarray in contemporary America stemmed from a betrayal of the principles of the Founders. Extending his earlier critique of libertarianism to the whole American political tradition, Bozell argued that the American Constitutional system had not only failed, but that it had to fail. Rejecting the distinction between liberal and conservative, Bozell insisted that America had been liberal right from the start. The American Creed—that is, any philosophy one could derive from the Constitution—had been from the start a revolt against God, an affirmation of the human power to shape the world apart from divine guidance. What was implicit in “Freedom or Virtue?” became explicit in these later articles: without belief in God (more specifically, Jesus Christ) it makes no sense to talk about values or the “permanent things” or any of the other warm fuzzy words traditionalist conservatives threw around in ecumenical settings. Americans had always placed freedom first, and that demonic impulse was now bearing its bitterest fruit in the affirmation of the freedom to destroy human life in the womb.

At the peak of his alienation from America, Bozell remained enough of a “movement” conservative to believe that this problem could be addressed through some form of political action. In 1970, Bozell and a group of anti-abortion activists who dubbed themselves the “Sons of Thunder” staged an event they called “Action for Life,” a protest outside an abortion clinic at the George Washington University hospital. The National Review was appalled. Its editorial assessing the event is revealing:

Viewed politically, it was probably worse than useless. Spanish Carlism, whatever its virtues in its local habitat, is surely exotic in the District of Columbia and the Sons of Thunder can have moved precious few of the unconvinced over to their side.

There are several issues here. First, Buckley and his editorial board had long been skittish on the issue of abortion; then as now, it is an issue mainstream conservatives would rather avoid. Second, the tactics the Sons of Thunder employed smacked of the black power and anti-war protests conservatives had railed against for years. Finally, and perhaps most interestingly, the National Review objected to the introduction of foreign symbols and slogans into American politics—Bozell and his fellow protestors wore red Carlist berets and shouted Spanish Catholic slogans such as “Viva Christo Rey!”

This last criticism, seemingly the most petty, actually speaks most directly to the vision of cultural politics emerging in Bozell’s struggle with America. The editors at the National Review were in effect accusing the anti-abortion protesters of being un-American. Bozell himself was beginning to see that the conservative tendency to make some notion of America as the ultimate arbiter of all moral and political issues was part of the problem. Anticipating some of John Paul II’s thinking, Bozell realized that positive, meaningful change on the abortion issue would not come simply by changing abortion laws. Unlike the contemporary Christian Right, Bozell rejected the idea of advancing legislation to restore a Christian America. Instead, he proposed a politics that would work toward building up communities that made it possible to be Christian in America. Bozell called this the politics of “the Confessional Tribe.” His own tribe was Catholicism, but his political vision could apply to any traditionalist community: “If Christians wished to offer a program to America, it would be spiritual lebensraum (breathing space). It would be freedom to work a soil, to breed a culture in which the Christian seed could grow. It would be the opportunity to build a city hospitable to Christian living.” This city, or really tribe, would have the Church as its foundational institution, followed by the family and then the school. The tribe would be a community of persons first and laws second. It would be based on affinity rather than coercion; exclusive, it would nonetheless be open to new members. It would, moreover, be a movement in, but not of, America: “Its purpose is not to reform the American system. It is not to destroy the American system. The movement’s purpose is to be the Christian system.”

Bozell’s tribalism proved too extreme even for the cadre of traditionalist Catholics that remained affiliated with Triumph into the mid-1970s. His mental health difficulties (bi-polar disorder) impaired his editorial abilities, and the audience for his unique blend of anti-communist, anti-capitalist conservatism continued to dwindle; Triumph folded in 1975. During intermittent periods of lucidity, Bozell continued to write perceptive essays on America politics and culture. Anticommunism remained his last link to mainstream conservatism, yet here again his writing reflected the old divisions between libertarians and traditionalists. Bozell observed the collapse of Soviet communism with delight, yet understood it as the triumph of virtue rather than freedom. The virtue he saw rising from the ashes of the Soviet Union was, moreover, the distinctly Catholic virtue of solidarity as articulated in the writings of Father Jozef Tischner, the philosopher of Poland’s Solidarity Movement. As a philosophy, solidarity proceeded from the assumptions that “every man is expected to help carry the burdens of the other man” and the only meaningful social action comes through sacrificial self-denial. The vision of true freedom Bozell invoked as far back as 1962 was a dream no more, but found real-world expression in Poland’s struggle against communism.

Such a reading of the greatest triumph of the conservative movement suggests little common ground between Bozell’s traditionalism and libertarianism. For the last thirty years or so, the conservative movement has achieved political success without having to find any common ground. Republicans have successfully moved mainstream politics to the right in terms of conservative ideals of free market capitalism and foreign policy militarism, yet on the cultural front, lip service to traditionalism has left abortion on demand the law of the land and offered no serious resistance to the advance of gay marriage. For intellectual conservatives who seek a traditionalism more robust than “family values,” Bozell’s vision remains an inspiration.

10 comments

Jacob

A year late, but I just came across this. I’ve been reading about L. Brent Bozell, Jr. for awhile now after discovering his writings while doing research for something else. I have a few points to offer.

Regarding Mr. Bozell, his collaborators at Triumph and Ultramontanism, it is important to remember the times in which they moved. The Catholic clergy and laity were rebelling in the wake of Vatican II. Sisters were leaving the convent and embracing radical feminism. Catholic universities were sending out declarations stating that they were no longer bound to upholding Church teaching. The papal encyclical on contraception was met with outright disobedience and condemnation from even the bishops. I see the Triumph editors’ sticking with the Pope more as fighting back against the tide of rebellion than any kind of actual ‘the Pope can do no wrong’ mentality.

As far as the reference to Bozell’s attachment to Franco and the idea of Catholic monarchy, Bozell was no idiot, though he was attached. I’ve never gotten the impression he was totally enamored with Franco; rather, it was more an admiration for a confessional state such as Spain where Catholics were still free to live out their faith lives with the state as an ally rather than an antagonist. The Habsburg Spain that represented the apex of that state was quite subsidarist in its approach to government, with the regions of Spain being more or less autonomous. It was only later under Bourbon government was absolutism imported from France. A man of Bozell’s intelligence was no doubt aware of such distinctions.

Fane

It’s fortunate that mainstream conservatism is closer to classical liberalism than traditionalism in this day and age. It seems to me that liberty and the industrial society have been the main forces behind the booming prosperity of the last few centuries – I’d hate to live in one of the distributist communes Bozell II proposed. The traditionalist’s rejection and hatred of liberty and industrialism is, in my opinion, unrealistic and stupid. I can only imagine the political and economic stagnation that would occur in a state guided by the traditionalist worldview.

Bozell was one of the more extreme traditionalists. Moving to fascist Spain to escape the evils of American liberty, and employing Carlist symbols and uniforms in protests on American soil seem pretty over the top to me. He also holds a contradictory political view similar to that of traditionalists today, who admire the strong, centralized Catholic monarchies and authoritarian regimes of the past, but go on and on about the virtues of subsidiarity.

It’s very disturbing that his son has some influence in the conservative movement today through the extreme, sensationalist, and journalistically subpar MRC Network. Though, ironically, MRC seems to identify more with conservatism as understood today, with its support of free markets, use of pro-freedom rhetoric, and pro-war stance.

JA

Thank you for this read. I had never heard previously of L. Brent Bozell. It’s comforting to know that there are fellow travelers who remain a remnant amongst so many Christians domesticated by the “mortal God” of the state and the worship of the self in liberal individualism.

Christopher Shannon

Thanks for your comments, Ray. My work on Bozell is part of a larger history of traditionalist/localist thought in twentieth century Europe in America. It is still very much in the early stages, but I hope to be publishing pieces from the work in the next few years.

I would also like to thank the other readers who took the time to respond. I agree with John Gorentz on Bozell’s poor choice of words, but agree also that the concept of breathing room is essentially sound. Like Joseph Harder, I do not share Bozell’s attraction to Franco (though the traditional Catholic culture that Bozell celebrates existed before Franco and could exist without him in the future), but I don’t think its fair to call him a simple ultramontanist. His take on the Solidarity movement contrasts sharply with the anticommunist chest thumping of a George Wiegel. Whereas most neo-conservative Catholics tend to confuse the vision of John Paul II with that of Ronald Reagan, Bozell linked the spirit of Solidarity to John Paul’s devotion to Divine Mercy, a devotional tradition that hardly aligns itself to neoconservative ideas of justice.

On a different topic, I must say that I do not quite understand D.W. Sabin’s comment that Bozell’s traditionalism plays into Big government conservatism (if not quite bigger government conservatism). In terms of its intellectual content, Bozell’s confessional tribe seems to me the only alternative to big or bigger government. Since the late 19th century, every free market/libertarian rhetorical attack on the state has only served to grow the size of the state; it was the state, after all, that created the “free” market. Whether Bozell’s ideas would “work” or not, I can’t say; it seems to me they are the only ideas on the table that haven’t yet been tried.

Ray Olson

Many thanks, Mr. Shannon. More about Bozell better stated and clearer than anything else I’ve read. Do you plan to write more about the traditionalist right? If so, you have a ready reader in me.

AC Trausch

Nigel- His son, L. Brent Bozell, is active.

D.W. Sabin

Fear has animated the Conservative Agenda for more than 50 years and I have not found that there are less things to fear as a consequence. Conversely, the liberal agenda has provided ample things to fear, working with their fellow big government fabulists in the conservative wing and so we find that the animating principle of government is “protection from fear”………..never a particularly firm foundation for an energetic polity.

The minor distinction is Big government vs an ever bigger government and the various skirmishes of the Cultural conservative virtually insure that we remain in this “big Government” paradigm.

Nigel

Doesn’t Bozell still write a column for Middle America News?

Joseph Harder

An interesting piece. My biggest problem with Bozell and his fellow Triumph types was their apparent effort to fuse together Carlism and Unltramontanism. Many , if not most, went on pilgrimages to Spain to lay wreaths at the Caudillo’s grave in the “Valley of The Fallen”.

Some of Bozell’s critique of American imperialism and materialism made sense; his alternative was, sadly, more Francoist than conservative, and more Papist ( in the worst sense) than Catholic.

John Gorentz

Unfortunate choice of words, “lebensraum,” given that the two usages have almost opposite meanings. But it’s a good concept as used here — one we can hardly do without. I think it’s the reason for the recent actions to deny conscientious objector status to those institutions that don’t want to take part in funding of contraceptives: the freedom of a group to act on its own principles is a threat to the Leviathan state.

Comments are closed.