Or, “Shaken and Stirred: The Cosmopolitan, the City, and the Regime of God”

Queens, NY

The following essay was presented at FPR’s annual conference in Louisville on September 27.

What I’m going to try to do today is convince you all that you can be a good localist, pursuing the kind of human flourishing that localism seems to us to promote, and live in New York City. I’m aware that this may be a hard sell. I don’t have any sheep in my yard, although I do have a yard, where I live now in Queens; where I grew up, in Manhattan, I didn’t have a yard, although I did have Central Park; there were, however, no sheep in Sheeps Meadow.

Periodically people attempt to do things like keep bees in Brooklyn, in hives on rooftops. What happened a couple of years ago when this became trendy was that the beekeepers started noticing that the honey started tasting kind of strange. The other thing they noticed that when their bees would fly back home after a long day of nectar gathering, they would, apparently, in the sunlight slanting low over Park Slope, be glowing red.

The Brooklyn beekeepers did some detective work, and figured out that what was happening was that the bees were all heading over to Red Hook, to the Dole factory, where they would stuff their little nectar sacks, or whatever it is, full of maraschino cherry juice that Dole had sitting out in big tubs, and then make honey out of that. Because apparently that was a lot easier than flying to Prospect Park and getting ahold of proper nectar. Essentially what was going on between the bees and the beekeepers was a conflict of hipster lifestyle commitments: the beekeepers were the crunchy-type hipsters, who frequent farmers markets, whereas the bees seem to have had more culturally in common with the glam-type hipsters, the ones who are a little bit slackerish and enjoy ironically retro cocktails made with maraschino cherries.

I could tell you more stories: about the bitter chicken conflict near Carroll Gardens, about the troubling fact that there are guys who show up very early every morning to fish off of Pier 17 down by the old Fulton Fish Market building, where there’s some particularly juicy garbage, the oozings of which feed a population of eels that are, by certain definitions, edible… This is the real face of urban agrarianism. It exists, it is growing, and I love it, except for the garbage eels, but it’s not that I’m claiming that you can live in New York City in quite the degree of organic woolly-footed hobbit-like splendor that Rod Dreher might wish; also you pretty much have to wear shoes, most of the time.

But you can live there well. And that gets us to politics. Why politics? Partly because I’ll touch on, later, what good urban politics can look like, but mostly because urban life is inherently political life, and I’m convinced that a lot of the hostility that conservatives have had towards cities is paralleled by their hostility towards the political as a category.

The political, we’re told over and over again, is downstream from the cultural; the family comes before the state and is quite distinct from it; politics is not the kind of thing that a real crunchy conservative would concern herself with, because she would be too busy growing heirloom cauliflowers or crafting artisan salad tongs.

I don’t think this is true. Man is by nature a political animal, which only really means that man is by nature the kind of creature that lives in cities– that’s what one strand of our tradition says, and the other strand says that though we began in a garden, we will end in a city; both strands, in other words, present cities– physical, actual cities, with (presumably) sewer systems and arts districts and everything, as the human telos, or at least as a crucial element of it. Both strands also present politics– the life of the citizen, the kingship of Christ– as key aspects of the human telos, and these politics take place– physically, actually– in cities.

It must, therefore, be possible to be urban and to be political and to be human, and I’m going to try to talk a bit about how to do that. But first I want to tell you about Jesse.

Jesse is thirty or so, tall, generally covered with boat-related grime of one kind or another and with a holster on his belt containing a rigging knife and a marlinspike. He’s committed to using the right knot in the right circumstance, and is the bosun of the schooner I sailed a bit on earlier this summer. He grew up in Washington State, spent a long time in Alaska, and has washed up– till his contract with the South Street Seaport Museum is up, at least– in Atlantic Basin, in Brooklyn.

“What’s Alaska like?” I ask– or someone does, in one of the long boat conversations.

He thinks. “It’s like New York,” he says: and explains: “You’re driving, and you look out the window, and it just goes on and on and on. Like taking the train in Queens– you just can’t believe how much of it there is.”

The how much of the city, the fact that it goes on and on, is what appalls him. And it’s what I love: I love how many neighborhoods there are in New York, how different each is; I love the fact that for some reason all the trimmings stores in the city, almost, have coalesced around West 28th Street; I love the fact that you can live your whole life here and then be walking around and run into a neighborhood full of signs in Serbian or something, and all the free newspapers in the little bakeries are in Serbian or something as well. I love how dense it is, how intricate. I love how specialized people can get– there’s a store down my block called Cheese of the World, and it indeed sells cheese almost exclusively; there’s another one near the Natural History Museum that I used to love to go to when I was growing up, which sells porcupine quills, ostrich eggs, and fossils, as well as taxidermized animals and possibly also equipment for taxidermizing them if you want to do that.

It’s these neighborhoods that make a city– not instead of its iconic and public places, but complementary to them. If you’ve only been to Times Square, you haven’t been to New York. To see London, wrote Dr. Johnson, “you must not be satisfied with seeing its great streets and squares, but must survey the innumerable little lanes and courts. It is not in the showy evolutions of buildings, but in the multiplicity of human habitations which are crowded together, that this wonderful immensity of London consists.” The same is true of my city, and it’s these intricate small alleys and bodegas that are the matrix of our truly human urban lives.

The complexity of London’s and New York’s undistinguished neighborhoods that Dr. Johnson and Jane Jacobs described, those back alleys off of Baker Street or Hudson Street, are places where human beings live and grow. And, indeed, are conceived. James Schall, draws on this smallness and materiality of urban life when he reflects on conception– “Incarnation, Redemption, these begin in tininess, in the least of our brothers, in the innumerable little lanes and courts.”

That’s all very well, say the localists, but the fact is you can’t possibly be self-sufficient in a city. This is true. And for cities like mine, it’s a stretch to imagine that our local foodshed could really even begin to address its demands, even if you limited yourself to considering the demands, say, of Japanese restaurants south of Fourteenth Street: and even if James Howard Kunstler and Bill Kauffman and everybody else in the Hudson Valley planted their market gardens exclusively with wasabi.

The fiction of Havana, for example, growing all its own vegetables doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. A marxist Noam Chomsky addict I knew a couple of years ago made me watch a documentary about how after the embargo and the fall of the Soviet Union, Cuba’s cities became self sufficient; the picture that was painted was of fire escapes overflowing with eggplants, in joyful defiance of George W. Bush; I mentioned this to my godmother’s husband who’d just come back from sailing to Havana and he said, baffled, but they don’t eat ANY vegetables in Havana. So I’m a little cynical about the notion that cities can grow all their own rutabagas on rooftops. New York is dependent on the container ships that pull in to its harbor every day through the Verrazano Narrows.

This is what so many localists reject about cities: Cities require, they think, that you live on cash exchange exclusively, live alone in a crowd, live without doing it yourself, whatever it is; and live subject to a cold bureaucracy– you can’t, after all, fight city hall.

Cities have also suffered in Christian assessment, over the years. Cities are Babylon, they’re dangerous; we are often told that as urbanites, we’ve lost many of the instinctive responses that would have made Christ’s pastoral metaphors meaningful to us. We don’t know from shepherds and wine-presses, wheat-fields and weeds.

How then can I claim that living in a city can provide an extraordinarily good foundation for a local life, a human life, and a life of discipleship?

It’s true that the medieval world that conservatives often look back to with longing was not urbanized: but we have to look further back still, look to the classical world that the New Testament describes, in order to truly get a handle on just how pre-modern city living is, and just how compatible it might be with an embrace of pre-modern virtue.

Just think about how difficult reading the New Testament must have been for those who lived in the world after the fall of the Empire and before cities began once again to thrive and trade: Because the world that the New Testament describes is precisely a world of cities, not a world of feudal manors or self-sufficient farms. We hear stories about the crowds pressing on Jesus, of impressive buildings, of money and banks and complex political structures, of public speeches to five or ten thousand people, and we find these easy enough to imagine, if we’ve been in Times Square or Wall Street. What would an eighth-century monk have made of the word “crowd,” of the idea of a place that was full of people you didn’t know, of a marketplace that was a sea of strangers?

“Christianity,” points out James Schall in Another Sort of Learning, is “a ‘city-oriented’ religion.” This city-orientation, this orientation to Jerusalem in the life of Christ, and to the new Jerusalem in the life of His followers, is paralleled in the other strand of the culture that conservatives love and defend: Schall notes that “Hostility to the city, so deep in part of our tradition and often in our contemporary sociological and development theories, easily makes us forget that Socrates barely ever left Athens.”

This can be overstated: it is not that the Bible doesn’t present eschatalogical images that are agrarian: we are told of building houses and planting vineyards in a way that would warm the heart of Peter Maurin; we are told of lions lying down with lambs; and while I can picture the latter happening in a city, on the steps of a fountain in some Italianate courtyard in the New Jerusalem, it does seem like a stretch to imagine the former in an urban setting. The vineyards of the New Earth are not in windowboxes or modest raised-bed gardens, I suspect. Moreover, there are implications that I think I see in the New Testament that part of the life of the world to come will involve precisely venturing out into the wilderness, and making it fruitful, as Adam was intended to do. It’s not that I’m claiming that the agrarian has no place in the Bible’s picture of our future lives; it’s that I’m claiming that the urban does have a place, and that that must mean that conservative rejection of the urban can be challenged.

What’s the root of this rejection? I think it has to do with a set of associations we have with cities, which cannot on examination be sustained. There is a conflation in our minds between the urban and the disembodied, the crypto-gnostic, the non-local, and it’s this conflation that I want to challenge.

The great virtues, the great human goods, that we here seek to preserve and celebrate are things like attachment to a particular place, and a deep personal engagement with the physical world, so that you’re able to work with skill to change where you live; to mix your labor with matter, with the ingredients of the soup you’re making, with the wires of the lamp you’re repairing, with the galvanized steel of the gutter you’re fixing, if not with the land in the sense of a forest or a pasture.

These things can be done, and done well, in cities. It is not urbanism itself that is dehumanizing, it is a corruption of urbanism. Good urbanism exists, and it invites a particular kind of activity that I want to describe as tinkering. People who live well in cities tinker with their cities. Not arbitrarily, but in a craftsmanlike way that takes account of the whole but attends to a part; respects the larger household that is the city and knows that the best way to serve it is to attend to the smaller household that you’ve got going on in an apartment on the Lower East Side. A kind of blend of Philip Bess and Jane Jacobs, is what we’re aiming at. You know what the city is, and you are responsible for this particular corner of it; you act in good faith, whether the corner you are tinkering with is a vacant lot you’re trying to turn into a garden, or a political machine that you’re trying to reform.

And this brings us to the purely political part of this case I’m making: what do good urban politics look like, and how might we think of them? What I’ve seen, for the most part, is that good urban politics look like this kind of tinkering: personalist, hyperlocal, but mindful of the whole: and I suspect that the best vehicle for them might be a massively reformed version of the old ward system that we talk about under the name Tammany Hall.

It is interesting to note, moreover, that the radical change that came over my city in the 1990s under the guardianship of Police Commissioner Bill Bratton came due to what was known as “broken windows” policing: the idea that violent crime could be curbed if small pockets of disorder, of de-creation, were attended to. This was supported by the concomitant idea that police needed to get out of their cop cars and start actually walking their beats again, to be able to get to know their neighborhoods at that level of detail. It worked. Neighborhoods that show signs of being lovingly tinkered with, their windows repaired, their window-boxes filled, are, in other words, actually safer. I’ve lived through this: urban security through community policing and publicly-encouraged DIY tinkering is a real thing that has made real changes in my lifetime.

This kind of thing takes –I’m sorry to say– some kind of centralized authority. Policing takes police; and if the best police departments are committed to as much local engagement and precinct-level decision-making as possible, it’s also true that subsidiarity is not the same as anarchism. Philip Bess’s ideas reflect this on an architectural level: however much it might be easier for a localist to stomach the idea of New York or Chicago if they tell themselves that really these cities are just collections of neighborhoods like small towns, it’s not true. They are collections of neighborhoods, but that is not all they are. There is a unity to a city that is a political reality, and that should be embraced, not fought against. It’s just that it’s a unity that is not uniformity, a unity that feeds and is fed by the variety of the city’s neighborhoods, households, and people.

So cities are places to love, to lovingly and physically engage with: places where you can be human well. There’s something else to consider, though. One of the things I think hyper-agrarian localists fall prey to is an inappropriately overrealized eschatology– not because they’re looking for utopia, exactly, but because they’re looking for something permanent, a permanent home. We’re seeking “sustainability,” but in some sense this is what, here, we can’t yet have– not entirely. We can have stewardship, we can be frugal, but every man under his own vine and his own fig tree must, this side of eternity, be a fragile state of things; there is no completely “normal” agrarian society to get back to; it never existed. And often our engagement with that life, if we are the sort of people who read Helen and Scott Nearing, is actually with the homestead in speech, Plato’s Front Porch Republic. Not always: there are, of course, real homesteads, real rural lives, and they are good, just as there are real urban lives that are good. In all cases, however, the best of these lives– the best homesteads, the best small towns, the best cities– point beyond themselves. Properly understood and lived, they are windows that open outwards onto an eternal community, the place of our desiring.

We are still in exile, and cities are after all a good place to be in exile. And as we live in the earthly cities of our exile, we can be sure that if we tinker well, that good bit of the city– that little bit of invention or repair, of tikkun ‘olam– will be taken up and will, finally, be part of the New Jerusalem. The work that we do to the glory of God, bearing His image well, He will, I believe, endow with a supernatural life, so that when in the eschaton the supernatural and the natural are married, we will see that work; nothing good, finally, will be lost.

But this is not to spiritualize everything– not at all. We cannot seek, really, to establish the eternal city here, by our own will– that would be to build Babel, and it would be a city that was characterized by a refusal to point beyond itself, a refusal to be an icon of the New Jerusalem. What we can do is learn to live in our own cities as in embassies of the New Jerusalem, as the New Jerusalem in exile. And so maybe we need to be thinking about the cultural institutions that have typified these kinds of exilic communities: the landsmannschaften that anchored new immigrants in their Lower East Side lives at the end of the 19th century; the coffeehouses that served as meeting places for scholars in exile from either of the totalitarianisms of the 20th century, where their papers were written and their journals read.

I want to turn now to something else that might be troubling us. So many of the great quest stories are essentially rural– the Lord of the Rings, the grail quests, Robin Hood, all tend to start out in what New Urbanists would identify as, say, Transect Three– I take the Shire to be Transect Three– and then move into Transect One: wilderness. Who are the heroes who live and quest in transects five and six, the urban core?

They are, in fact, right in front of our faces: we have a whole genre of novels that show us that a life that’s lived in these alleys and courts and bars and bodegas is fully capable of bearing the same weight of glory that the life of any medieval knight ever did– or any Yankee homesteader. Not because the alleys are secretly perfect or un-corrupt, but because they are in some sense a proper human habitation, a corrupt version of something good, and the appropriate backdrop for a soul-building quest.

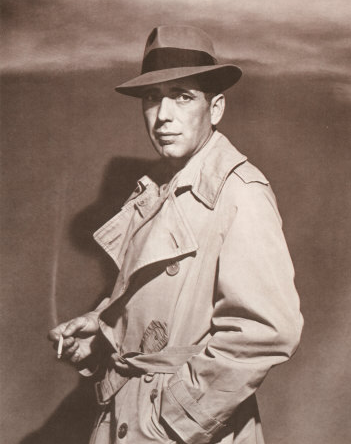

My father claims that The Simple Art of Murder is the greatest work of moral philosophy of the twentieth century. I haven’t actually read it yet, but there’s a quote from the author’s introduction that I think gives a clue to what he means:

Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean, who is neither tarnished nor afraid. The detective must be a complete man and a common man and yet an unusual man. He must be, to use a rather weathered phrase, a man of honor.

This is the honor of the shamus, of the undercover agent, of the spy. The quest he is on may be a bit grittier, a bit more likely to be shot in black and white, than the quests we’re used to, but the object of it is the same.

You might call this kind of urbanism the Little Way of Raymond Chandler. It is a way that calls us to imitate another man who walked down the mean streets of another city, neither tarnished nor afraid.

9 comments

Elizabeth

This prompted me to peruse about half of The Drowning Pool – 133 pages or so – to see how many similes I could count. (I’m using the Vintage Crime Black Lizard edition from May 1996). I counted thirty four and no doubt missed a few. I haven’t done the legwork, but I think some of the later books might have a slightly higher ratio. That’s a lot, but in any case I would argue that many of Macdonald’s similes are so strong that they infinitely enrich the work. Not only that – they are so strong that they put many “serious” writers of fiction to shame.

http://postmoderndeconstructionmadhouse.blogspot.com/2014/11/ross-macdonald-drowning-pool.html#.VHVcctKUeRZ

dave walsh

Thanks. Too much to respond to in brief, so one thing: for me a difference between localists and globalists – one similarity being I’m beginning to loathe those words – is that localists acknowledge some contingency to their identity. Not a city – country thing, but a being shaped versus a self creation thing. Hard to swallow these days, I suppose admitting being shaped a confession of lack of agency, rather than benign or desperate or intelligent adaptation and accommodation. Hard to develop a local intelligence if we are not from anywhere – thing is, a choice made excludes.

And if one wants to go on and acknowledge a more fundamental contingency to being, well. That’s deep water.

Jordan Smith

Really enjoyed this piece. It’s what FPR has needed for a long time–a robust defence of the city. Maybe I’ve misjudged this Polet fellow after all.

Although I have lived in an extremely rural setting for over a decade, I have always been a bit of an urbanophile. And now I have returned to the city for a six month stint, and already I can see that your wonderful “tinkering” observation rings true.

Anyways, it will be fascinating to see what happens to to both urban and rural environments when The Long Emergency finally (and inevitably) arrives.

Julie Gabrielli

I thoroughly enjoyed this article. Thank you for bringing humor and erudition from a wide variety of sources into a compelling and fresh narrative with which I wholeheartedly agree. I especially love your take on tinkering. There is just one thing I’d like to offer for consideration, sparked by your phrase: “part of the life of the world to come will involve precisely venturing out into the wilderness, and making it fruitful, as Adam was intended to do.”

You have put your finger on a long history of human centrality when it comes to what we call “the environment” or “nature.” My challenge is with the assumption that one has to “make” the wilderness fruitful, when, as in many creation and teaching stories the world over, including the Garden of Eden or the proverbial lilies of the field, everything is provided for us, as one member of the greater community of life.

It’s interesting to note that most oral, place-based cultures do not have a separate word for “nature,” because they do not view themselves as separate from it. Everything is kin, and they experience reciprocity and interrelatedness with the whole living world.

I have trouble even finding words for this, since it is so far from the stories of human exception, superiority and dominion on which I’ve been raised. This Separation is the foundation upon which all modern “civilized” cultures have been built, including – I speculate – Christianity.

Ronald Wright’s “A Short History of Progress” brings great perspective to this story of human mastery over the living world in the form of the march of progress. Human civilizations throughout history – and regardless of ideology – have tended to overwhelm the ecologies of their settings, in part because of their insistence on the story that wilderness is but raw material to be harnessed and tamed, to support human ends. When reciprocity falls by the wayside, ecologies collapse and civilizations fail.

Your piece reminded me of some wonderful studies in grad school about this tension between nature and culture, Eden/paradise and the city. Have you come across any of these?

William McClung, “The Architecture of Paradise” is a rather self-consciously scholarly look at the competition between garden and city as models for paradise in this life and the life to come. Worth the effort though.

Sylvia Doughty Fries, “The Urban Idea in Colonial America,” chronicles the history of ideas of the city that America’s founders brought with them, including quite sophisticated approaches to politics and town building. So it’s not all anti-city, as Thomas Jefferson would have us believe.

Leo Marx, “The Machine in the Garden,” which tackles pastoral ideal in America – including the confusion between wilderness as “howling desert” versus source of nature’s bounty – and the inevitable challenges presented by technology.

Thanks again for a wonderful piece, and good luck with continuing to prove that cities have an important role in the localization movement. You’ve given me a lot to think about, and also renewed hope for our future.

Radoje Spasojevic

A very convincing piece, though the ochlophobist in me still says there are just too many dang people in one place for my comfort.

I would like to check out the Serbian bakeries though.

I think a great deal of the tension felt by, for lack of a better term, the rural/localists towards cities, lies in the fact that many of the policies, ideologies, and cultural works that have been destructive to authentic rural communities have been birthed in more-or-less urban environments. That these policies, et al have been equally destructive to authentic urban community is small comfort when it seems that rural communities seem powerless in the face of the power of cities as creators of a cultural hegemony.

The is a tension within Christianity towards the city, in Psalm 55:9-11 there is wickedness in the city, and Christ calls Jerusalem the city that stones the prophets, and pronounces woe on towns that have rejected His message and His works. Yet, the image in the end remains that of the Heavenly Jerusalem (which I am certain will have Serbian bakeries).

Still I think no less of an authority than Wendell Berry has said something along the lines that a thriving urban localism (and the humility that sees urban places as not sufficient to themselves, but dependent on their hinterlands) will go a long way towards creating the conditions for the renewal of rural communities.

Comments are closed.