BURNED-OVER DISTRICT, NY — As New Horizons races past Pluto this week, I offer this blast from the recent past, a tribute to the discoverer of the ninth planet (International Astronomical Union be damned), Clyde Tombaugh. The piece first appeared in The American Conservative in 2010 and is included in Poetry Night at the Ballpark and Other Scenes from an Alternative America, which no naked-eye (or just naked, for that matter) astronomer should be without:

Four score and zero years ago in Flagstaff, Arizona, Clyde Tombaugh, a bespectacled 24-year-old just off the farm from Burdett, Kansas, joined an exclusive fraternity of merit from which he has been posthumously booted. Clyde found a planet which those costive bastards of the International Astronomical Union now say isn’t a planet!

Our family rambled into Flagstaff a few years back, bunking in the downtown Hotel Monte Vista, a splendidly faded and haunted monument. We slept in the Clark Gable room, though Clark seems among the least likely Hollywood haints. (I wouldn’t stay in a Sal Mineo room for nothin’!)

Flagstaff is also home to the Lowell Observatory, founded in 1894 by the Boston Brahmin Percival Lowell, who was convinced that he had seen with his own eyes Martian-made canals on the Red Planet.

Lowell was a rich man with a magnificent obsession and the integrity to pay for it himself rather than milk the taxpayers. If his astronomers never did find life on Mars, one found something even less expected — Pluto.

In contrast to the computerized robotism of astronomy today, everything about Pluto’s discovery was fallible, painstaking, whimsical — human.

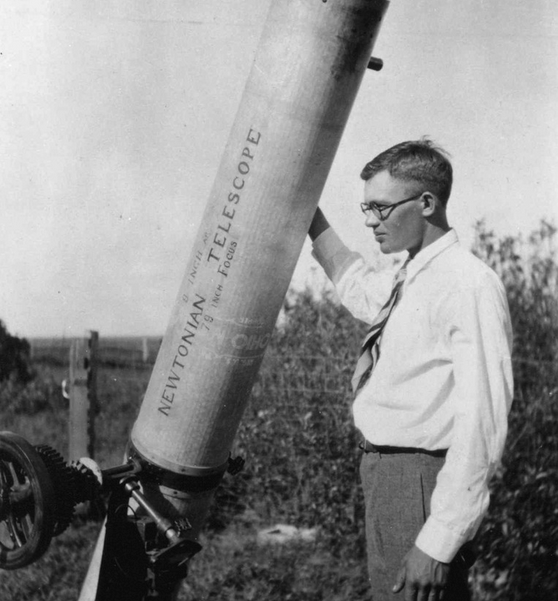

Discoverer Tombaugh was a classic American boy who spent his Kansas days in the wheatfields and his nights at the eyepiece of his homemade telescope. On cloudy evenings, he taught himself Greek and Latin; on Sunday afternoons, his pasture hosted the neighborhood touch-football game.

College was out of the question. So was a “career,” until in one of those message-in-a-bottle tosses characteristic of bright and naïve provincial lads, Clyde sent his freehand drawings of Mars and Jupiter to the Lowell Observatory.

His timing was perfect. Observatory director Vesto Slipher was looking for a talented amateur to work long hours at low pay searching for the “Planet X” hypothesized by Percival Lowell. Vesto decided to give the kid a shot. So in January 1929, Muron Tombaugh drove his son Clyde to the train station at Larned, Kansas, whence the youth departed for Flagstaff with Dad’s parting words ringing in his ears: “Clyde, make yourself useful, and beware of easy women.”

In his history of Great-Uncle Percy’s colony of the starstruck, The Explorers of Mars Hill (1994), William Lowell Putnam writes that Slipher desired not a theoretician but a plodder for the “boring and tedious” planet search. Using a “blink comparator” microscope, Tombaugh spent up to nine hours a day comparing photographic plates of identical patches of sky taken at intervals of several days.

At about 4 p.m. on February 18, 1930, “I saw a little image popping in and out,” Clyde told his biographer David Levy, himself a romantic comet-chasing poet of the Arizona sky. Clyde walked down the hall and into the director’s office. “Dr. Slipher,” he said, “I have found your Planet X.”

The obscure Kansan, his era’s version of an industrious office intern, had become the third person in recorded history to find a planet.

He became famous, in a “yes, but” way. In William Lowell Putnam’s phrase, Clyde was Pluto’s “fortuitous discoverer, the photographic technician Tombaugh.”

Ouch! Bring me my tea, boy, and step lively!

Pluto — it’s a good name, isn’t it? Sure, it’s no Uranus, that gift to generations of snickering schoolboys, but it evokes the underworld and honors with its first two letters Percival Lowell, whose batty and litigious widow asked Clyde, “Are you willing to have the planet named Constance?” (He was not, though Mrs. Lowell shared Pluto’s iciness and highly irregular orbit.)

You might regard Tombaugh’s story as a parable of the diligent clerk, the persevering drone, but there was an ardor in his arduousness. Bearing only a diploma from good old Burdett High — “Let each sheep wear his own skin,” said Thoreau of such honors — Clyde seized the chance he was given by the outliers at Lowell, which was “virtually an outcast in professional astronomical circles,” as Tombaugh later wrote. (Soon thereafter, the principal of Burdett High convinced the University of Kansas to award the planet discoverer a scholarship. Talk about a distinguished freshman! Clyde eventually taught astronomy at New Mexico State in Las Cruces, becoming that city’s most famous resident since Billy the Kid-killer Pat Garrett.)

Eighty years after Clyde broke the news to Vesto, Pluto is in a categorical netherworld — more out than in. Those who expelled Pluto from the planet club are, in the main, credentialed astronomers employed by government-subsidized facilities in which a 21st-century Clyde Tombaugh would be wearing a hairnet and ladling mac and cheese in the cafeteria.

David Levy told me that Tombaugh, who died in 1997, was saddened in his final years by the suspicion that he and Pluto were in for a demotion. “Dwarf planet” they call it now. But maybe that’s okay. Pluto, Flagstaff, Clyde Tombaugh — small really is beautiful.

2 comments

David Naas

Thanks for this.

Too often we forget discoveries are made in a combination of the outrageous and the unlikely.

Years ago, I read somewhere, Tombaugh’s professors were mildly embarrassed to have the discoverer of the Ninth Planet (Yes, it IS!) sitting in their classes. when all they had discovered was navel lint.

JimWilton

Thanks for this. I note in an article in the NY Times today that astronomers have named the very large heart shaped region in the new photographs of Pluto : “Tombaugh Regio”.

Comments are closed.