Laura Dunn’s The Seer: A Portrait of Wendell Berry (later retitled Look & See) begins with the blurred lights of cars speeding along freeways and the barren wasteland left by mountaintop removal coal mining. While Wendell Berry reads one of his Sabbath poems decrying the nightmare of industrial destruction, we are shown sped-up scenes from this ever-hurrying, ever-expanding economy, an economy that may bring profits to some but that leaves many more lonely and wounded in its wake.

Then the music cuts out and the screen goes black. After a long pause, the sounds of birds, insects, and footsteps begin, and we find ourselves walking along a Kentucky lane in fall, following a dog as it explores the margins of the leaf-strewn way. The camera moves at the pace of an easy stroll, sweeping to look through the trees to the valley below. The rest of the film explores the contrasts between these two paces, these two ways of moving through places, these two ways of seeing.

Throughout the film, the camera walks down this same lane in different seasons, showing us the beauty that can be seen by looking carefully rather than quickly. In this way, the place itself becomes the film’s protagonist, the place as seen through the eyes of its inhabitants. Wendell Berry himself never appears in front of the camera. As Laura Dunn explains in a recent interview about the film, “Instead of focusing on the way the world sees Wendell, … let’s look at the world the way Wendell sees it.” And so the film gives us a composite view of his place, one that mimics the forty-pane window in his long-legged writing cabin. We hear from neighboring farmers, migrant workers, his wife Tanya, and his daughter Mary. Throughout the film these differing perspectives are supplemented by Wendell Berry’s voice narrating his own view of the place.

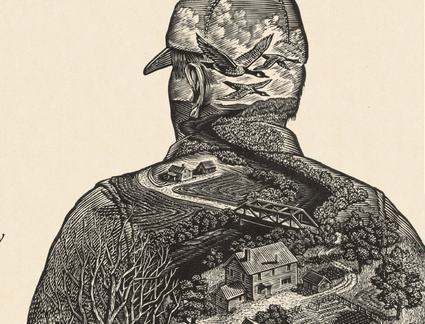

The film is punctuated by marvelous Wesley Bates engravings that act as chapter breaks. The arc of the narrative follows the argument Berry lays out in his seminal book The Unsettling of America: industrial agriculture damages the land and its people, making it increasingly difficult for farmers to make a healthy living. Yet as she does in her previous feature-length documentary The Unforeseen, Dunn succeeds in humanizing those who find themselves caught up in the industrial world. The farmers she interviews who use large equipment and work land measured in the hundreds of acres come across as participants in a system they dislike but cannot escape. They’re not dumb nor are they evil; they understand exactly how the system works, but they don’t know how to beat it.

What makes this documentary beautiful is not only its sympathetic portrayal of its subjects, but also its deliberate and careful camera angels. The camera takes us through these rural places slowly, often from a child’s perspective. Laura and her husband have six young boys, and she has clearly learned to see the world through their eyes. We look directly into the face of a piglet or a lamb from its own level. We see the hands of farm workers and gardeners and craftsmen and artists. Such sympathetic viewpoints embody Wendell Berry’s own efforts to see the world humbly.

The care with which The Seer is put together may be seen most clearly in a sequence where Dunn is talking with Berry about our cultural and agricultural fragmentation. Yeats’s poem “The Second Coming,” with its haunting line, “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold,” epitomizes this condition for Laura. As she admits to Berry, “That theme, unfortunately, seems to define the world that I’ve come of age in. And so there’s this need to try to find a way to piece things back together.” Berry concurs, telling her that we live in an age of divorce where “things that belong together have been taken apart.” The proper response to such disintegration is the work of humble, faithful care. As Berry tells her, “You take two things that ought to be together, and you put them back together. Two things, not all things.”

Tanya expands on this theme, noting that people often ask what they can do if they don’t have a home. She tells them to stop somewhere and make a home where they are. At this point we see an image of a rainbow resting over a home along the Kentucky River, subtly critiquing our tendency to search elsewhere for some elusive pot of gold. Tanya continues, “There are ways to put this back together, I would think. It never was perfect, but there’s been a lot left out lately.” When Tanya speaks these lines, we see a group of children playing with a dog. One child stands apart from the group, off by himself. An adult walks over, extends a hand to the child, and brings him to the group. In this moment we see the simple yet profound ways by which young and old, animals and people, can be put back together.

The care with which The Seer, as a film, is knit together offers hope that our disintegrated culture and damaged land might likewise be mended by faithful, loving work. So although the subject of industrial agriculture is sobering, the film strikes a hopeful tone. The film encourages viewers to follow the example set by Berry and his family and neighbors who are doing good work in damaged places. It challenges us to find two things that ought to be together and then to put them back together.

Two Birds Film gave me access to a screening of The Seer, and it premiers at SXSW on March 11th. They are raising funding for final production costs via Kickstarter. Hopefully, the final version of The Seer will be released widely so that it can receive the attention it and its subject deserve.

1 comment

Comments are closed.