And what there is to conquer

By strength and submission, has already been discovered

Once or twice, or several times, by men whom one cannot hope

To emulate —but there is no competition—

There is only the fight to recover what has been lost

And found and lost again and again: and now, under conditions

That seem unpropitious. But perhaps neither gain nor loss.

For us, there is only the trying. The rest is not our business. (East Coker, V)

Amid all the bomb throwing and doom projecting going on this political season, I appreciate the good folks at Ethika Politika calling for thanksgiving. We sojourn up a luminous path. And we should let our guides know their perseverance in prudence is casting light.

I teach history and political theory at a classical Christian school North of Detroit. School let out early today. After reading my friend Susannah Black’s fond recollections of her professor, Hadley Arkes and my coreligionist Wesley Hill’s celebration of his hedgehog of a teacher, Scott Hafemann, I determined to join their mellifluous chorus and start singing the praises of sage teachers. As I wandered from my apartment to the local coffee house, laptop in satchel, ready to write, I determined, a proud Michigander and Bohemian Tory at heart, I should give thanks for my staff wielding guide up the seven storey mountain: Russell Kirk, sage of Mecosta. Inside the Dessert Oasis, I scanned the blog requirements and felt my heart sink. Ethika Politika wants us to give thanks for people we know in a face to face, voice to voice, tipping back pints after class sort of way. Well, Dr. Kirk and I belong to the same community of souls, the same communion of saints, so despite the rules, I am going to sing his praises.

Gothic cathedrals, Spanish pilgrimages, and John Henry Newman’s account of conversion persuaded Kirk to enter the waters of baptism. I entered by other means. My family commuted to The Fisherman’s Net every Sunday when I was in grade school. Hippies, bikers, and suburban wanderers founded The Net back when the Jesus Movement was spreading like wildfire across Detroit. I remember dad insisting, as Casey Kasem counted down, “if a church is alive, it’s worth the drive.”

Pastor Alex, chief minister at The Net, had joined a Detroit gang, the Bagley Boys, as a teenager. Initially attracted to the gang on account of the members sharp looking zoot suits and reputation around the neighborhood, Alex questioned his path when the gang members started dealing drugs and stepping up the violence. Soon, after his Christian girlfriend left him and a policeman warned him that he was heading down a ‘dark road’ he committed to follow Christ if he led him out of this situation, wound up at a charismatic prayer meeting, and started, as he puts it, taking orders from a new general. The Holy Ghost also filled Tom Neme, a keyboard player touring with Bob Seger in Europe. After writing most of Noah for Bob Seger and The System, he abruptly left life on the road, moved home, and found Jesus. He began playing keys for The Net. God changed men in the basement of this old commercial building.

When I moved home after college to study literature at a local graduate school, my housemate (a boyhood friend who let me rent out his basement) invited me to come back to The Net. I expected the rock band and road to Damascus stories. But I was surprised to hear Pastor Alex quoting T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets. Scuffling around during fellowship hour, chatting with strangers who knew my parents and knew my story, I was inching toward the exit, drinking coffee, struggling to appear inconspicuous, when Pastor Alex approached. He shook my hand. He asked what brought me home. He insisted even poor college students need to eat. He would take me out to lunch.

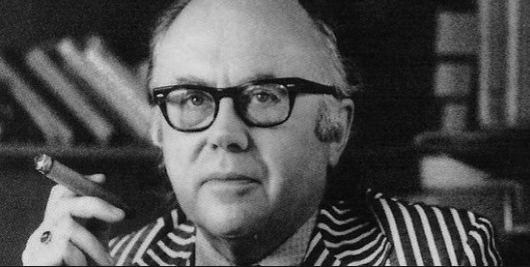

Traffic humming behind us, Pastor Alex and I sat outside and ate Mediterranean at a strip mall walking distance from my condo. He asked me about my studies. I mentioned my favorite professor, Dr. Hoeppner, was teaching a course on 20th Century poetry. We had just read Eliot’s The Wasteland. I asked how Eliot happened to make it into Sunday’s sermon. Pastor Alex explained he came to love Eliot after reading Russell Kirk’s The Sword of Imagination. A signed copy of the book, dedicated to Kirk’s allies at The Net, still holds a prominent spot in the church office.

Piety Hill, ancestral home of the Kirk family, shines brightly in the minds of those who share Kirk’s medieval imagination and love of the permanent things. Before his final pilgrimage to Mecosta, Pastor Alex made a trip to Detroit to track down a quality cigar for Dr. Kirk. Walking beyond the house to Dr. Kirk’s library, a renovated toy factory, he was startled by Clinton Wallace, a homeless man adopted into the Kirk family. Wallace, noticing the cigar in Pastor Alex’s hand shook his head, “Mrs. Kirk won’t like that. She doesn’t want Dr. Kirk smoking anymore.”

Pastor Alex lifted the cigar and examined it, “oh, I had no idea,” he explained. Then, undeterred, he knocked on the library door. Dr. Kirk invited him to come inside. Dr. Kirk asked Pastor Alex if he’d like to smoke. Pastor Alex explained he did not himself smoke but had purchased the cigar for Dr. Kirk before the gentleman outside informed him he gave up the practice. Dr. Kirk pocketed the cigar in his suit coat. He continued the conversation as if nothing had transpired. Pastor Alex told me he was relieved to see someone in my generation reading Kirk and taking up the torch. He paid our bill and asked me to speak at church.

Most English teachers in my department turned a blind eye to the divine in literature. Dr. Hoeppner woke up early and composed poetry while pacing around the Rochester suburbs. He did not oppose philosophical and theological engagement with poetry — he encouraged it. His class felt like stepping into an May afternoon after a long winter. He grew up attending daily Mass and singing in the boys choir. Catholic friends found the pre-Vatican II church oppressive. Dr. Hoeppner remembered the Latin services and Catholic schools fondly. Unlike professors who described Eliot as reactionary, bigoted, or second-rate, Dr. Hoeppner introduced him with the conviction he was due for a positive reevaluation. Sitting on a stool in front of the class, he laughed at the decision to mark “I grow old, I grow old, I will wear the bottom of my trousers rolled,” on his dorm room wall as faintly ridiculous. He, like Eliot, had forgotten to act his age.

We chatted about the Church one day after class. I mentioned my frustrations with the popular caricature of the Bride of Christ as one of the chief facilitators of abuse and oppression, an institution of bigotry and patriarchy. Despite her flaws, she does the work of Jesus, serves the sick, orphaned, widowed, and imprisoned. Dr. Hoeppner agreed and pointed to the Roman Church’s opposition to the Iraq war and monopoly capitalism as examples of the Church’s prophetic role in society. As I read Kirk’s Eliot and His Age and The Sword of Imagination, I gained confidence that the Church inspired beauty and charity. Academics, by and large, failed to see what Chesterton realized about our longings: “We do not really want a religion that is right where we are right. We want a religion that is right where we are wrong. We do not want, as the newspapers say, a church that will move with the world. We want a church that will move the world.”

This was my first year teaching economics. When the headmaster led me to my classroom and shuffled through the books on my shelves, I was overjoyed to notice Kirk’s name among the authors. As I taught my students about political economy, everything from Aquinas and the middle ages to Marx and the industrial revolution, Kirk challenged us to consider the purpose of economics. We discussed his reflections on Wilhelm Ropke and what it takes to maintain a humane economy. I share Kirk’s respect for Chesterton and introduced the students to distributism (the conviction that small is beautiful, and there should be a just distribution of political and economic power). One of my seniors approached me in the spring and asked if I would advise his thesis on the origins of socialism in America. We had developed a good rapport during a couple drives home from school. I lost most of my sight in college and caught rides with the Spanish teacher, the Kindergarten teacher, and, in a pinch, this particular student.

When the day arrived for my advisee to defend his thesis, he called me earlier than I anticipated, saying that he was outside my apartment, ready to drive us back to school for the evening presentations. I hustled up the hill to ensure the questions I had prepared for the presenters did not go unasked. I opened the door and downplayed my heavy breathing and absent mindedness. Kirk and I share the same opinion of cars, “mechanical Jacobins”, friends of revolution, required, sad to say, for getting around suburban Detroit. Kirk’s stubbornness went so far that he refused to drive. For me, driving isn’t exactly an option. As we made our way to school, my student talked about his decision to run track and study journalism or political economy at Hillsdale in the fall. I recalled Kirk’s time teaching at Hillsdale. Reflecting on the year, I was eager to continue trying. The sun was warm, the windows were open. I gave thanks.

2 comments

Pastor Alex Silva

Clinton,

I thoroughly enjoyed reading your essay. You drew me in with your writing .You helped me participate in your walk of faith and your viewing the Body as His Bride. Dr. Kirk would approve of your appreciation of him. God bless you son. Pastor Alex July 2016

Comments are closed.