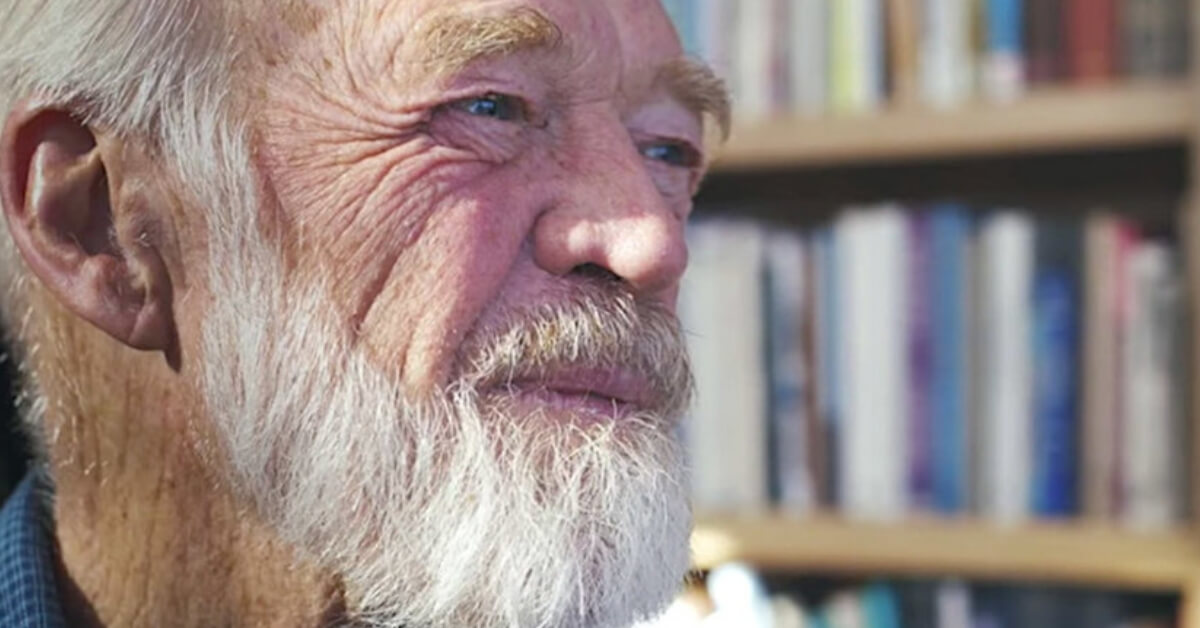

One of my heroes of the faith is dead. Eugene Peterson experienced death, but certainly not its sting, as he uttered his final words, “Let’s go,” on Monday, October 22. If I am being honest, I am struggling to adequately articulate his loss, but I’ve never been more certain of my hope in resurrection. Eugene’s death may be an opportunity for us all to “practice resurrection” as we stop to reflect on a race well run and look forward to the restoration of all things.

I never had an opportunity to meet Eugene in person, but his writing has lived with me, formed me, and mentored me for the last thirteen years. I believe writing is an intimate exchange between persons, and I think Eugene did too. In Eat This Book: A Conversation in the Art of Spiritual Reading, he says, “Language is not primarily informational but revelatory. The Holy Scriptures give witness to a living voice sounding variously as Father, Son and Spirit, addressing us personally and involving us personally as participants” (62). As I have eagerly “eaten, chewed, gnawed,” and received his words in “unhurried delight,” I have received more than mere information about pastoral ministry or spiritual formation (11). Instead, I have been mentored by a humble man, faithful husband, and diligent minister of the gospel as he revealed his heart on every single page that he has written.

I read many tributes with far more eloquent prose and reflections perhaps more substantive than I can offer. I fear being redundant, and I don’t aspire to top some of the beautiful pieces already published, so I have decided to write a personal letter to Eugene. I think this is fitting because our relationship thus far has been one-sided. I have been a beneficiary of his writing for all of my ministerial formation. I can only pray that somehow in the great cloud of witnesses he hears my heartfelt thanks or maybe has the opportunity to read my reflections in the New Jerusalem—come, Lord Jesus.

Eugene,

Where to start? I suppose, I will start from the beginning. We first met through your translation of the “Beatitudes” in Matthew 5. I was a senior in high school, and I was attempting to memorize Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount with some friends for a school project. “Blessed are you when you are at the end of your rope. With less of you there is more of God and His rule” (Mt. 5:3). My mentor showed me your translation in The Message and I was transfixed. This specific verse would live with me for the next several years. During this time, I became a husband, experienced war and failure on the mission field, and came home to the unexpected incarceration of my father and the subsequent fracture of my family. With less of me there is more of God and his rule, indeed, brother. I clung to this verse for quite some time as a fearful young man coming to grips with my own limits and faults and with the effects of sin. Thank you for the gift of encouragement while enduring hardship and suffering.

After high school, I followed a faint call to ministry by majoring in biblical studies in college. This call felt fuzzy to me until I came upon your clarifying book the The Contemplative Pastor. I sensed God’s call to ministry, but I didn’t feel like I fit what was modeled for me by the personalities I saw on “stage” from week to week at church. I began to wonder if I belonged in the midst of talented communicators and professional worship bands. Then I read this as you reflected on one of my other favorite authors, Wendell Berry,

[O]ne of the genius aspects of pastoral work is locality. The pastor’s question is, “Who are these particular people, and how can I be with them in such a way that they can become what God is making them?” My job is simply to be there, teaching, preaching Scripture as well as I can, and being honest with them, not doing anything to interfere with what the Spirit is shaping in them… Am I willing to be quiet for a day, a week, a year? Like Wendell Berry, am I willing to spend 50 years reclaiming this land? Am I willing to spend 10 years, 20 years, 50 years with these people? (4)

I found this vision of pastoral ministry to be a welcome oasis and a prophetic word in a world of promotions, mega churches, celebrity pastors, and platform building. Your vision of pastoral ministry has shaped my imagination and charted a new path forward. You gave me a small, humble, but holy vision. I would wonder at night what it could look like nurturing a congregation for 10, 20, or even 50 years? Instead of imagining crowds, conferences, and book deals, I began to imagine giving myself to a little congregation, baptizing their kids, feeding them the Eucharist, and burying their dead—to me there’s no higher calling or better vision, and I have you to thank for that. You gave me a clear picture of what it means to be an intimate, loving, nurturing, pastor-scholar. You helped me to understand what it means to be the “unnecessary pastor” rather than succumbing to seminarian ambition.

Finally, as I finish seminary and enter discernment to be an Anglican Priest, your words on the liturgy have been a source of confirmation in my call to a particular family within the Christian tradition:

Liturgy gathers the holy community as it reads the Holy Scriptures into the sweeping tidal rhythms of the church year in which the story of Jesus and the Christian makes its rounds century after century, the large and easy interior rhythms of a year that moves from birth, life, death, resurrection, on to spirit, obedience, faith, and blessing. Without liturgy we lose the rhythms and end up tangled in the jerky, ill-timed, and insensitive interruptions of public-relations campaigns, school openings and closings, sales days, tax deadlines, inventory and elections. Advent is buried under ‘shopping days before Christmas.’ The joyful disciplines of Lent are exchanged for the anxious penitentials of filling out income tax forms. Liturgy keeps us in touch with the story as it defines and shapes our beginnings and ends our living and dying, our rebirths and blessing in this Holy Spirit, text-formed community visible and invisible. (Eat This Book, 74)

Your emphasis on words, place, and poetry emphasize the formative power of narrative. We are formed by the words, narratives, and contexts that surround us. The competing forces of the world around us are not merely neutral. Christian worship, liturgical calendars, and life rhythms are ways in which we allow the Christian story to seep into our bones. These are the ways that we inhabit the narrative arc of the gospel as actors on a divine stage. This is how we learn to see that “Christ plays in 10,000 places.”

So, Eugene, you’ve labored for a lifetime on behalf of the Church. You’ve written, pastored, preached, and poured yourself out to equip the saints for the work of ministry. The Lord knows how big of an impact you’ve had on my life, not to mention the many others you’ve touched through your ministry. In light of this, I wish to echo Bono’s words to you after you completed translating The Message, “Take a rest now.”

We’ll see you soon,

Kris