Cedar Falls, IA. Spring mowing in Iowa releases the sweet pineapple aroma of Chamomile. I discovered this stubborn, single stem plant in our driveway gravel, creeping improbably across compacted zones like it owns this place. Driving from one side of the lawn to mow beyond a building, I trim it so often that it barely tops my toes. Also known as Common Mayweed, this herb defies annual baths of RoundUp, subzero winters, snow plows, and herbicide spills. Green sprouts proliferate even after the grader blade shaves the gravel so flat it pools water like beach sand. Mayweed is a persistent gift that teaches me how to thrive in unlikely places.

Chamomile varieties have been cultivated since the Neolithic. Commercial producers harvest a blue oil and components of the flowers and leaves for pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and teas. One source claims that people around the world drink more than a million cups of Chamomile tea daily. The tiny plant yields bioactive phytochemicals that treat ailments from hay fever and hemorrhoids to insomnia and muscle spasms. Native to northeastern Asia and northwestern US, sources say Chamomile was likely brought eastward across America with the Lewis and Clark expedition as they returned to St. Louis in 1806. Rich folklore and traditional healing treatments document its spread westward from Asia.

On our farm, Mayweed is a wild companion, my souvenir of our history here. We bought this property from Federal Land Bank in September 1987 and did not meet the former owners until later. Foreclosed in 1983 during the agricultural crisis, this dairy and general farm had been operated by generations of one family for almost one hundred years. Neighbors declined to buy the land, a common protest strategy, leaving the acreage to the care of renters. The property’s ragged edges showed how quickly vegetation reclaims the spaces people leave behind.

We moved here in late November after most herbaceous plants and shrubs had withered. I would have liked to walk around the yard with the former owners to learn what grew where. Even if we had met then, they probably would have directed my attention away from the weeds. We had never lived west of the Mississippi or on a farm, and though many common plants and trees were familiar in this northern climate zone, many were new to us. We’d come from West Virginia where eroded, hillside soils formed from decayed woodlands over rock and clay. Iowa offered a new nature with lush prairie sods and soils created by glacial drift layered over ancient marine sedimentation.

Our first year here presented a calendar of outdoor surprises. Perennial onions, hyacinths, and tulips appeared after the snow melted. Rhubarb emerged like an organism coming out of hibernation. Asparagus fingers poked through like Rip Van Winkle calling out to meet the newcomers. Rangy willows waved their yellow catkins at us when we looked out the kitchen window. A solitary cherry tree by the road, exposed to harsh northwest winds for countless winters, finally exhaled some blooms after much effort. Peony fists shook in the wind along the west ditch. I would have enjoyed a crowd of white or lavender Lilacs, even a few Hollyhocks. It’s just as well that this place had few frills. Roses and fussy ornamentals would have perished from my neglect.

I feel at home with seemingly insignificant plants like Chamomile that blend in as part of the scheme of things. Pineapple Weed is another popular name for this miniature cousin of the daffodil. It sprouts above the grit with a lime-green stalk topped by a yellow, cone-shaped, button flower stuffed with potential. Thousands of its seeds weigh a fraction of an ounce, an abacus of years counting forward into the future. We notice Mayweed in northeast Iowa at the beginning of June when that unmistakable sweetness rises again.

The area where Mayweed grows best now was the site of the property’s original house. This small, clapboard structure had been used as a garage and metal-working shop after the family moved into the big house across the driveway, built in 1924. By the time we bought the place, the shop was a multi-generational mix of wasp nests, spiders, parts, nails, oil slicks, and metal paraphernalia that outbuildings accumulate as if by magnetism. We salvaged odd tools and dimensional lumber, and bulldozed the rest to expand the driveway for maneuvering large equipment.

The demolition exposed that patch of ground to daylight and rain, activating a botanical legacy that hosted the Mayweed. The tropical smell enchanted me, an unexpected scent in the driveway when I crushed the flower buds and leaves while walking. Mayweed thrives in cut-over plots and waste ground such as former construction sites. Iowa is a well-manicured state where tiny Mayweed can go unnoticed. Still, the plant lives intentionally: one hundred days from seed to seed. Millions of seeds spread everywhere every year, scattered by mowers, blown by the wind, and walked someplace else on the bottoms of our shoes.

As new owners of this property and newcomers to Iowa, we had a pick-and-choose loyalty to the farm’s many components. We offended some people and delighted others when we destroyed the original small house, sold and dismantled the concrete silo, torched the chicken house, and allowed a small grove of unkempt walnut trees to be harvested. Some of the adults who’d grown up here feared we would tear down the dairy barn, a safe deposit box of summers spent filling and emptying the hay mows, playing hide and seek, and tending to livestock chores before breakfast. To them and to us, the emblematic structures seem permanent although we all know they are not. What is necessary to one generation may be tossed in the burn pile by the next.

It seemed a neighborly thing to do when we agreed to sell the dilapidated township schoolhouse on our property’s northeast corner to Jim Grupp. He wanted to gift it to his sister as a surprise 65th birthday and retirement present the following year. Their home place is a half mile north, they’d attended the school, and both had become educators. He moved it 33 miles south to Reinbeck where she lived and refurbished it as an antique store on Main Street. On our corner, the absence of what was once a township landmark has been restored as a quarter acre of good farmland with a similar but different cultural value.

I see the plants and trees as iconic elements of the local landscape, much like a red livestock barn or a utility tractor by the machine shed. Wild and domesticated plants and trees add to the dignity of our immediate environment and define it as a place where families work and live. In April, you can smell the impenetrably frozen ground come alive out of winter’s darkness. The land itself is a breathing organism so complex and so generative that just paying attention to it feeds a deep place that renews our souls.

The co-creation of landscapes through crop farming initially unsettled me. We leaped from backyard scale to industrial volume in one season, upending my notion of being part of a bigger picture that meanders over time to one that, like Chamomile, lives from seed to seed in a hundred days. Each Iowa season measures out three months of specific characteristics that disappear when the next one phases in, emphasizing the now of a vivid present. Each farm owner’s time on a property is dynamic, adjusting the tension between growing and dying, meaning and stewardship, preserving and releasing.

Whole sections of farmland across our county and state grow seedlings at roughly the same rate in May, as if farmers collaborated to quilt the land with tufts spaced six inches apart. Before you can turn around in a good year, the wall of corn rises up so thick in late June that you can’t see more than a foot deep into any field. Indigenous peoples honor the spectacular corn tassels of late summer in elaborate headdresses, symbols of a fruitful and prosperous season. Harvest transfers the grain into bins and the spectacle ends as farmers prepare the cropland for winter.

Tillage options, conservation practices, water management, and crop rotation change the ways our farms look and produce over time. Smart farmers invest in a balance between developing, conserving, and harnessing the soil’s capacity for productivity. Dominant crops draw energy and resources like urban areas. It took me a while to see that no matter how controlled the production farmland may be, abundant life will flourish all around the edges, too, if it’s allowed.

Some herbalists theorize that people move to where the plants can heal them. I should have conducted a plant survey to compare with our soil survey. Iowa had the continuity and stability we needed, with a banquet of plants that could feed or soothe us, entertain or confuse us. I could gather flowers for a vase or greens for a salad without planting anything. Summer ditches filled with brilliant orange Daylilies, Milkweed, Wild Parsnip, native grasses, vivid lavender Bergamot. Aromatic sprays of white flowers in July became rich purple Elderberry jams in the fall. Queen Anne’s Lace, Cattails, and Goldenrod defined early August. The dried minarets of flowering Motherwort soothed my heart in the wintertime when herbal teas brought the outdoors inside for healing and hope.

I harvested buttery dandelions on April 23 once, the British day for making dandelion wine, and sipped a sweet gold liquor that fall. I recognized plantain, white clover, and other everyday first-aid plants that tolerate a mown lawn. Dainty Violets nestled in the grass, as if a princess and her attendants had tossed lavender petals across the yard. Violets also grew in the understory of our mature Red Cedar windbreak whose trees had thunder-struck tops, bark crusted over rotten barbed wire, and a poke-your-eye-out maze of dead branches that stuck straight out from the trunks. The lovely Violets, delicate symbols of love and faithfulness, complimented the Cedar, prized for its essential oils that preserve what is good and worthy.

I could have lived better if I’d eaten the Mulberries that crept into the windbreak, crowding the lanky cedars. Growing ten feet in a year, these invaders held a treasure of medicinal qualities I didn’t learn about until decades later. Silkworms, which we don’t have, favor the leaves. Raccoons, which we do have, climbed up the ladder of Cedar branches to grab the ripe fruits. Mulberries treat cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, anemia, and arthritis. One source describes the plant as a “powerhouse of nutrients” with everything from fibers and carbohydrates, to lipids, antioxidants, and beneficial polynutrients. I might have avoided several health problems later if I’d been half as wise as the raccoons and eaten my fill every June.

I also ignored the pesky message of Burdock, or Cocklebur, that clung to me after every autumn walk like a post-it note. English settlers brought Burdock to America. Commonly used in Chinese medicines and as a food, Burdock roots, leaves, and seeds can boost immune systems, lower blood pressure, kill germs, reduce fever, and purify blood. It can treat cancer, colds, acne, dry skin, and rheumatism. Burdock’s first year elephantine leaves spread out close to the ground, just below the reach of mower blades. In the second year, Burdock zips upward like a tree, sprouting prickly purple cannonballs on the ends of flower stalks that dry into a brown burr. A coarse biennial herb, one treated here as a noxious weed like Russian Thistle, Burdock has admirable qualities of persistence, purpose, and adaptability.

This alluring array of plants, crops, critters, birds, livestock, and trees that come and go with the seasons coached me in respecting the big cycles of life. These forces influence us but are beyond our impact, no matter where we live. Here the flower succession marks time as the earth tilts away from the sun, cutting back daylight until the sun passes the meridian of our horizon and drifts ever southward. The land has a permanence, yet it shifts. Rocks have a permanence too, yet they move. Whether barely perceptible or terrifyingly obvious, the creative vitality on earth teaches us about movement and change as essential forces we need not resist.

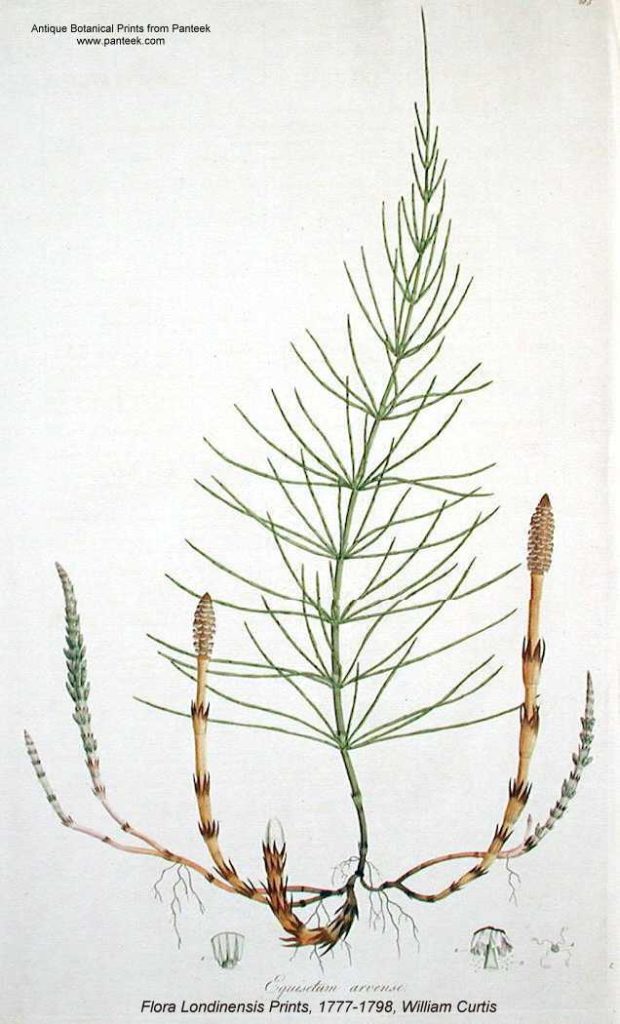

The oldest plants on our property are the Horsetail or Scouring Rushes that poke up like pencils along ditches in the spring. These are the oldest plants anywhere they grow. The genus Equisetales emerged during the Carboniferous era when the Appalachian Mountains were being formed and basic plants with seeds began to grow. I knew Equisetes from when I worked at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia after high school. Enormous cross-sections of Equisetes trunks and slabs decorated with its delicate branches filled reinforced cabinet trays. Dinosaur food, Equisetes varieties formed huge forests that died and compressed to become the coal we harvest for fuel. Medicinal supplements use Horsetail components in the treatment of kidney and bladder stones, urinary tract infections, brittle fingernails, joint diseases, and bleeding problems. The plant absorbs silica and is so coarse when dried that it’s used as a sandpaper for polishing the reeds of musical instruments, or bundled into a scouring brush.

Yet Equisetes are insubstantial; they look like the idea of a plant or a drawing a child might make. Its leaves are like sheaths cut from tissue paper, wrapped around the hollow stem, segment jointed to segment like a telescopic toy. Hundreds cluster in groups. Plants are virtually indestructible, thriving in rich, moist soils. Equisetes and hybrid corn were all that survived a recent herbicide application. We have the oldest and the latest plants side by side in our fields.

Plants teach me how to grow where I am. Like Pineapple Weed that thrives in wastelands and Equisetes that prosper in rich soil, I learn to adapt to the conditions around me. It may not be the place I prefer, or the conditions I like, but resilience is a skill I can cultivate. Resilience and adaptation are powerful change agents. These vital forces transform me into a dynamic version of myself that remains true to my natural being.

When I feel weary, it’s a signal that I need to go outside. A simple walk shifts my unease, returning me to the place where God puts me. Every square inch of our property has been disturbed in some way. Even the rocks rise up through the ground each year, as if hoisted by geologic tides, the thawing and heaving of deep winter frosts. Come springtime, a new crop of rocks should be harvested before field planting begins.

When all else fails, I go sit on a rock. Spending time on a rock is like investing a day at the beach where everything that is everlasting, bound to the Earth in the water’s everflowing cycles, becomes an enchanting mystery. The sea breeze freshens our faces. Our toes squish into the sands of time. A rock in my yard will be remarkably the same long after I’m gone. That fact of nature assures me that the trouble of today will pass too, adding its small part to the whole.

A walk around the yard connects me to the grand scheme of abundance. I can collect a cup-full of ripe flower buds–Mayweed, Red Clover, Violets–while the water boils in the kitchen for a delicious tea. A pocketful of Catmint will draw the barn cats closer as they nudge me to see what I’ve brought. When all the plants disappear under winter’s cover of whiteness–so improbably and completely vanished it’s as if they never existed–I can bring us both back to life in my teacup on a dreary day in January.

These resurrection rituals are so elemental that I can forget who I am and just think, “cup of tea,” taking for granted the bounty around me. Accepting what I’m given helps me steward the divine life force. Seeds of the kingdom of God grow everywhere: in the driveway gravel, under the trees and rocks, speckled among the leaves and twigs in the roof gutters. Even in a few minutes staring out the window or imagining my favorite places, I can allow myself to grow.

We’ve lived here long enough to experience the start-to-finish, whole life of many things, something I never imagined. As a newcomer to farm country in 1986 I knew we would have a future here but I simply couldn’t imagine it. As an adventurous young adult, I did not have a long view then, except as an abstraction. I did not have my own history in any place that lasted longer than ten years. I had no vision of our past here as the first in our biological families to move west of the Mississippi.

Recently we cut down 30 Austrees we planted 25 years ago from sticks that came in a package delivered by UPS, trees that served us and our environment well. They had outgrown their time, both above and below ground. Tree limbs broke off in storms, threatening passersby and buildings; their vast root systems clogged drainage lines so completely that the tiles had to be replaced. The stumps revealed how the old trees were dying on the inside, a natural life cycle in the grand scheme of things. Cutting them down feels like a fresh start on a place that’s no longer called by the former owner’s last name. We’ll never be locals like they were, but our stories add a small part to the bigger picture of this place on Earth.

Once we stopped finishing out hogs over 15 years ago, the activity and traffic of animals, people, and equipment ceased too. Tree seeds had already rooted invisibly into the barnyard alley’s expansion cracks. Cedars, Mulberries, and Willows busted through the concrete, creating shelter for critters and birds and wildflowers. I catch a whiff of pineapple now where I least expect it, renewing my faith the way a mustard seed makes inroads in a mountain. The tiniest effort at the living edge of the universe becomes a turning point on a new path forward.