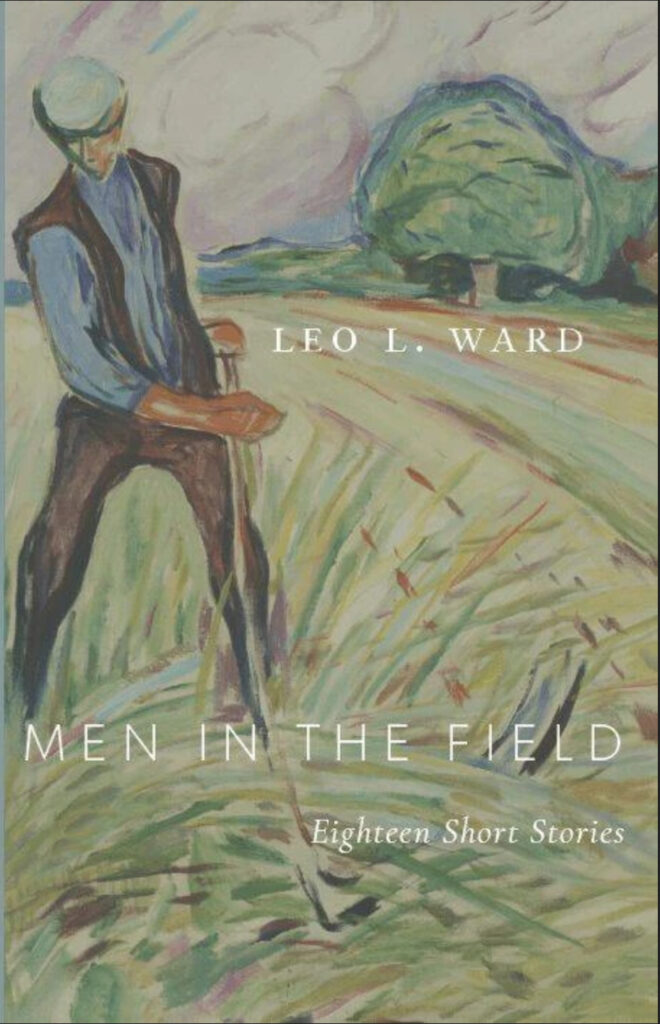

Lexington, VA. In 2020, Cluny Media republished Men in the Field: Eighteen Short Stories by Leo Lewis Ward, C.S.C. I had never heard of Ward before, but the description on Cluny’s website intrigued me:

Men in the Field was first published in 1955, and since then American farmers have witnessed irrevocable changes to their work and way of life. These eighteen stories harvest the humor and pathos, history and myth, of the American cornbelt in a bygone era. The result is a compelling, episodic narrative of American life, in which each moment gleams with their author’s deep love for the earth and his abiding respect for the men and women who till and tend it.

I grew up on a small farm and have great affection for the works of Willa Cather and Wendell Berry. I ordered the book in the hopes that Ward’s stories, like theirs, would avoid the besetting sin of so much farming literature—flat characters in flat settings, simplifications of either the pastoral or anti-pastoral variety. I hoped that Ward’s stories of Midwestern farmers would inhabit the thicker middle between those extremes. I hoped they would depict complex characters engaged in that most fundamental yet complex of endeavors.

While waiting for the book to arrive, I tried to find out a little more about Father Ward. I learned that he played varsity basketball at Notre Dame as an undergrad and entered the university’s founding order—the Congregation of Holy Cross—upon graduation in 1920. His Notre Dame obituary notes, “Father Ward was one of the few priests at Notre Dame who was awarded an athletic monogram.” After his ordination, Ward returned to his alma mater as an English professor.

Strangely enough, he was not the only Leo Ward on the faculty of Notre Dame and in the Congregation of Holy Cross. His confrere Leo R. Ward was a leading Neo-Thomist philosopher and Jacques Maritain scholar, but also a fellow farm boy and poet. They became great friends. In the preface he provided for Leo R.’s memoir, acclaimed Notre Dame President Theodore Hesburgh explains that “we always called him Leo R. (rational) Ward to distinguish him from another legendary teacher here, Father Leo L. (literature) Ward.”

Leo L. Ward edited an abridged version of John Henry Newman’s The Idea of a University, and he co-authored a pair of textbooks with another Notre Dame English professor, John T. Frederick. These were the publications of a seasoned and thoughtful educator. They grew out of an adulthood devoted to the university. But Ward also published a number of short stories and poems. These had deeper life roots. They grew out of a childhood spent on a farm in Otterbein, Indiana, where he was born in 1898. His stories and poems of rural life appeared in prominent publications, such as Poetry, Prairie Schooner, and the Jesuit magazine America. Frederick published the collection Men in the Field posthumously, after Ward’s death from a heart attack in his mid-fifties. The collection seems to have received little attention outside of the Catholic press and outside of Frederick’s own promotional efforts on behalf of his friend’s work.

This cursory research piqued my interest in Father Ward but tempered my highest hopes for his fiction. Given its limited reception, perhaps Men in the Field would not be a neglected masterwork after all. When the Cluny reprint arrived, though, I soon discovered that it was indeed fit to sit on the shelf alongside Cather and Berry. The stories are somewhat uneven, which is not surprising in a posthumously published collected. Some are evocative vignettes rather than fully developed narratives. The rural drawl of Ward’s Indiana farmers occasionally seems overdone. But the best stories in the volume offer Cather-esque explorations of the links between place and people. As in her fiction, the landscapes pulse with vitality. Ward’s stories also offer visceral, dynamic descriptions of farming work—the work of human, draft horse, and machine. In his preface, Frederick (who was himself an accomplished fiction writer), observes that “Ward knew this [farming] life intimately and lovingly. No detail of fact or function escaped his attention; no variation of attitude or experience exceeded his understanding” (i). The stories are remarkable as well for their dense layers, for their social, psychological, and emotional intricacies. The first two stories in the collection provide good illustrations of these strengths.

The lead story is titled “The Threshing Ring.” It is about a group of neighboring farmers, the “ring” of the title, who have purchased a mechanical grain thresher together. The narrative begins at the train station. The farmers eagerly await the new machine’s delivery alongside young “Mr. Kenyon, the expert who had arrived yesterday from the factory” (2). When the thresher does arrive, it takes them two hours of coordinated effort to unload it from the train.

The opening paragraphs introduce Burl Teeters as the most troublesome member of the ring. He is “a little man with a slight bump high on his back” (2). Teeters stands apart from the other farmers on the train platform. He “seemed to pay no attention to the excited talk going on all about him, except to throw an occasional scowl over his shoulder when Jay Westwright was talking” (2). Indeed, throughout much of the story one wonders if Teeters is part of the ring in any sense beyond a legal share in the machine, if he is truly a friend and fellow. He is opinionated, bossy, and often belligerent. The other farmers are affable and neighborly. They share their ideas about how the work should go, but they are also respectful of each other and of the new machine and deferential to the “expert” Kenyon. This is especially true of Westwright, who serves as Teeters’ foil. When Westwright suggests to Kenyon that they unload the machine near the engine room, he does so “in a quiet, respectful tone” (2). Teeters, by contrast, jumps up on the thresher as soon as the train stops, tugging “violently” on a belt and working levers (4). He badgers Kenyon during the unloading and scorns Westwright’s humble competency. “Yeah, you think you’re runnin’ the whole works,” Teeters says to Westwright. “Well, I’ll tell you one thing you’re not runnin’. An’ that’s the engine. I’m the one that’s running that engine” (6). Westwright’s anger flares for a moment, but he contains it and ultimately grants Teeters’ wish to be the engineer. He tells the others that Teeters can “probably learn to run it all right, if Mr. Kenyon would just keep a close watch on him for a while” (6).

But Teeters does not want to be watched, and disaster strikes when they are out in the field. Teeters jerks one lever too many and the huge belt connecting the steam engine to the separator breaks. The out-of-control engine, with Teeters still perched on top, nearly runs into the separator, on which Westwright and others are standing. The farmers, perhaps grateful that a far greater disaster has been averted, do not berate Teeters, but he is preemptively enraged at them, and especially at Westwright: “Yeah, you won’t say anything! You don’t dare, that’s what you don’t. You don’t dare say anything about my runnin’ that engine. It’s your fault anyway, an’ you know it. You bought that engine an’ you got slippin’ levers, that’s what you did” (11). Teeters lets out a manic laugh like the squeal of a strained, off-kilter belt, “growing higher and more shrill until at last it suddenly dropped to a sort of jerky cackle” (11). He ultimately storms out of the field in a huff. It seems that his loose connection to the threshing circle is as shredded as the belt.

Yet that evening, as the men relax in Bert Helker’s farmyard, they tell an incredulous Kenyon that Teeters will be back the next day as soon as the new belt arrives, acting like the accident never happened and assuming he will continue as engineer. Kenyon is even more incredulous when they say that they will let him run the engine again. He asks, “But couldn’t you just kind of ease him out some way? Maybe get him out of the ring some way. Might buy up his share in the machine, boys. Couldn’t you do that?” (14-15). Westwright says that he does not think they could. Teeters would not sell for one thing. And, as Helker, adds, “Don’t think the boys’d want to put him out exactly” (15). Even if Teeters does not honor the thicker bonds of neighbor and community on his end, the rest of the ring honors it on theirs. (This calls to mind the deeper kind of belonging that Berry’s fiction describes as “membership.”)

The start of “The Threshing Ring” suggests a familiar pattern in farming stories—the arrival of the machine that signals a new era, that will perhaps bring new efficiencies but might also break up what is good in the older, more communal ways. The near collision with the steam engine, which could easily have killed some members of the community, can be read along such lines. Kenyon’s suggestion that the ring buy out Teeters might also plausibly point in this direction. One senses that Teeters would buy them out if he could, that he would readily trade a barn full of machines for shared work with his neighbors.

But in the end the story is less about modernization than the perennial problem of dealing with a difficult personality. It is less about the malfunctioning of machines than about human mysteries. Kenyon, for one, gains a new appreciation for the latter. In the first half of the story, up through the accident, he is always referred to as “the expert.” In the second half he is just Kenyon. His exasperation at Teeters reveals a limit to his expertise. Here the farmers in the ring have wisdom to share.

Unless, of course, one reads the farmers as unwise. Their evening conversation ends when they hear Teeters calling his hogs in the distance, “shrill and thin, somehow like an impudent, insistent challenge too distant to be answered at all” (16). Maybe the other farmers are dupes for not answering Teeters’ challenge more directly, for putting up with too much from him. Aren’t they ultimately as beholden to his “impudent” call as the hogs?

This is plausible given the ambiguities of the story’s ending, but it does not seem like the best reading. There are hints throughout the story that there are limits to what the ring will put up with from Teeters. There are moments when he comes close to pushing Westwright too far, for instance. And the farmers do not plan on allowing Teeters to ruin another belt and cause another accident. Westwright tells Kenyon “to stay right around that engine. Just practically run it yourself, Mr. Kenyon” (15). They seem to know that Teeters can be a capable enough engineer if the necessary instruction is thrust upon him. They are aware of his abilities as well as his flaws. They also seem to view Teeters’ impudence and imprudence as a burden they must bear as best they can. Perhaps they disperse when they hear Teeters’ call because it reminds them they will likely need the patience born of a good night’s sleep. They also seem to feel sorry for Teeters. This is laced with indignation and probably a measure of contempt. The men in the ring are decent but still human. When Teeters calls his hogs in the darkness, Ambrose Mull observes, “That’s a Teeters for you, callin’ his hogs this time a night when ever’body else has his chorin’ done and forgot about it a couple hours ago” (15). There is a restlessness and a lack of fluidity in Teeters. He cannot, for whatever reason, find the same rhythm of work and rest as the others, and that is cause enough to shake one’s head.

“Drought,” the second story in Men in the Field, deals with one of farming’s most basic trials. It focuses on a small cast of unnamed characters—a man, a woman, and a child—and it is less clearly situated in time than “The Threshing Ring.” The premise, characters, and temporality are thus archetypal, but the descriptions are vividly particular. “Drought” begins with the farmer steering a horse-drawn plow over desiccated ground: “The corn stretched away, grayish and dead in the blinding light. He knew every blade in the fields was cooked and shrivelled by the drought. Farther away he saw other cornfields, mere strips of gray haze drifting toward the shimmering horizon” (19). Ward distinguishes different heats and the farmer’s experience of them. Out in the open fields, in the direct sunlight, “the heat was wreathing visibly upward from the earth into the vast white sky. Farther away he could see other teams plowing, dirty smudges of cloud trailing through a sea of quivering light” (20). The barn, on the other hand, “was full of dead, motionless heat” (20). At lunch the exhausted, desperate farmer sits down in front of a “plate of steaming food” (20). His wife seems isolated from him, “strangely cool and comfortable” (21). One can imagine the look on his face, the tension he exudes. This tension, as much as the heat, seems to separate him from his family: “Even the child did not come to stand beside him now, or pull at his shirt and ask him to put jelly on her bread” (21). After lunch he lies down for a few moments in the spare shade of a maple tree, where “seared blades of the grass tickled the sensitive, burned skin on the back of his neck” (21). Then he goes back to the fields once more, to the great clouds of choking dust and the prairie’s “vague disk of seething heat” (21).

During the afternoon, though, clouds gather on the horizon and the wind picks up. The draught finally relents. The farmer drives his team across the fields in a pelting rain: “A kind of crazed gladness seemed to possess him. His voice broke above the hollow roar of the wind. And now he was laughing, and shouting wildly, his voice sometimes rising almost to a kind of sobbing frenzy, as he went leaping on through the storm” (24). He arrives back at his porch and hoists his child onto his sopping shoulders “with a great swoop, then turned and pointed a wet arm out into the storm” (25). The story thus swings from despair to joy, even from death to life: “The man smiled as his eyes moved slowly over all the stark outlines of the prairie. He felt the whole earth living again. And deep within him, he felt his breath coming fresh and cool” (25).

But there is a third act in this primal drama, and it is tragic. The rain subsides, but “a kind of distant clattering arose. The man heard it growing louder, and coming rapidly closer. Then, only a few moments later, he saw the first white pebbles of the hail come dancing over the grass of the yard” (26). The hail shreds his rejuvenated corn and his rejuvenated harvest hopes. His wife tries to get him to come inside the house. He turns away to hide his tears: “‘No,’ he said kindly, ‘I must go out to the barn now. Haven’t even unharnessed the horses yet” (26-27). In a way, the story ends where it begins—with perseverance, with a farmer carrying on with his work despite the manifest failure of his crop. Even with the ravages of the hail, though, the storm still seems to have softened something in the man’s heart. He is no longer near a boiling point, no longer isolated from his family. He is in grief, but he can now speak “kindly.” He is not grimly driving his horses across his fields as he was at the story’s beginning. He is instead going to care for them in the barn.

While Ward was a priest, religion is rarely at the fore in the collection. It is more implicit than explicit. The members of the threshing ring are humble and exceedingly patient. They are more Christian than Classical in their virtues. They suggest that the steam engine’s near miss of the separator and the men standing on it is a miracle. They quickly leave this topic behind, though, perhaps out of a sense of reverence. “Drought” dramatizes the deep connections between perplexity, gratitude, and agriculture, connections to which many ancient religions gave ritual shape and expression. There are also biblical echoes in the story, though, especially in the farmer’s Adamic toil in the dust, and perhaps too in the rainstorm’s fleeting, tantalizing hints of an Eden not entirely lost. The farmer ultimately undergoes kenosis, and this allows for some renewal of hope and love even within the disaster.

This seemingly baseless hope calls to mind a more overtly religious poem I turned up while researching Ward. He published it in the April 26, 1941 issue of America. It is titled “Meditation for Harvest”:

I know how quickly the blossom

Falls in the rain,

How soon the green-gold fades

From the grain.I know the world as a shadow

Soon will pass,

And nothing is much greater

Than the grass.Only the dead black branches

Of one bitter Tree

Will bear their sweet Fruit

Deathlessly.

This poem would make a fitting epigraph to Men in the Field. One senses that it reveals the hidden spiritual heart of these stories of satisfaction and woe, of virtue and vice.

“‘Meditation for Harvest’ was reprinted with permission of America Press, Inc. All rights reserved.”