Fort Smith, AR. I come from a rather unusually eclectic religious background. After being raised in a Southern Baptist culture under, perplexingly, a Calvinistic framework, I wandered through various iterations of liturgical traditions before the pull of grace came for me through Catholicism. I share this to say that my perspective on vocation—or calling—wears many layers. As is the nature of the sacraments, this concept of “calling” has been the thread through which I’ve sought to make sense of various forms of sense-making—of how God comes to earth and asks us to follow. What has at times carried a dark, if almost traumatic, connotation now bears in me a richer weight infused with the Catholic understanding of grace’s heft, a substance in this life that is a sign of greater things to come.

Such thin spaces subtly pervade Sally Thomas’s debut novel, Works of Mercy. As a Wiseblood Books publication, Thomas’s work adds a worthy contribution to the growing contemporary Catholic literary community while drawing from a deep well of other memorable writers (such as the main character’s favorite, Robert Southwell). For me personally, I often wanted to place Works of Mercy most closely alongside Graham Greene’s novels because of their similar conceptions of how the sacraments can remain tethered to us throughout our lives—how grace often remains inexplicable and, thank heaven, beyond the power of our own meager influence. At the same time, Thomas emerges as an original voice filled with thoughtfulness and reflection without becoming too cerebral to keep readers riding the tide of her story.

On the surface, what begins as a simple story unfolds delicately: an aging widow keeps house for the parish priest and attempts to maintain her distance from any relationship more intimate or demanding. However, as Kirsty Sain remains committed to the community of the Church—attending Mass and confession regularly, keeping her life in tune with the year’s liturgical rhythms—Kirsty finds herself encountering opportunities to love others and serve them more deeply. What begins as a passing friendship after church with a large, rambunctious family (the Malkins) evolves into a more inextricable arrangement; Kirsty finds herself stuck with a pitiful, wounded kitten who nonetheless becomes her household companion in an otherwise drafty, empty house left to her by her late husband’s family. As for other men in her life, Kirsty discovers herself becoming more attuned to the quirks of their young priest who appears ill-equipped for the intimacies of their small-town parish community. To her own surprise, she begins to see a local handyman as an almost-son and finds a kindred spirit in Howard Malkin, the Jewish father of his otherwise-Catholic family who Kirsty continues to care for in both spiritual and practical ways as their lives grow further connected. In each instance, these men are convincing as fully realized characters who do not detract from Kirsty’s story but beg reflection on how we might each respond to this question of vocation—of choosing to answer (whether by affirmation or avoidance) God’s call of love in our lives.

In the case of Father Schuyler, for instance, a writer of lesser skill might take more pleasure in caricaturing him as a rigid, young traditional Catholic who does not belong in today’s post-Vatican II priesthood. Under Thomas’s deft eye, however, he emerges as a human being whose cracks (along with his earnestness) enable him gradually to identify more authentically with those he has been called to serve—perhaps becoming a richer representation of Christ in the process. This also does not come at the expense of more traditional conceptions of Catholicism, which is refreshing. Howard, the Jewish man who fell in love with Janet young and now follows his family to Mass, eventually experiences a rekindling of his own religious heritage that bears difficult consequences. Thomas does not neatly resolve either of these characters but instead leaves their narratives open to the ongoing possibility that grace may continue to restore their souls.

To an extent, I read these two male characters as foils—not because of their religious inclinations, necessarily, so much as the ways they respond to their circumstances. Whereas Father Schuyler becomes more aware of the need—to borrow a phrase from my evangelical youth—to “meet the people where they are” and begins to allow a little of his humanness to appear in an attempt to connect with his parishioners on a personal level, Howard responds to his own crisis—a critical point in the novel which I will not give away—by distancing himself from his family, apparently seeking refuge in his faith while becoming unable to maintain a steady presence in his own home. In both cases, these men raise questions of the degree to which our own faith can serve as a compass—or a comfort—before we must find others with whom to experience it more fully. Perhaps the need to inhabit this tension faithfully is what was meant when I was taught to “live a life worthy of the calling you have received.”

Around the middle of the novel, Kirsty experiences a brief though debilitating illness that serves as a sort of turning point in her awareness of the need for other people in her life. Recalling family members now long passed, Kirsty reflects:

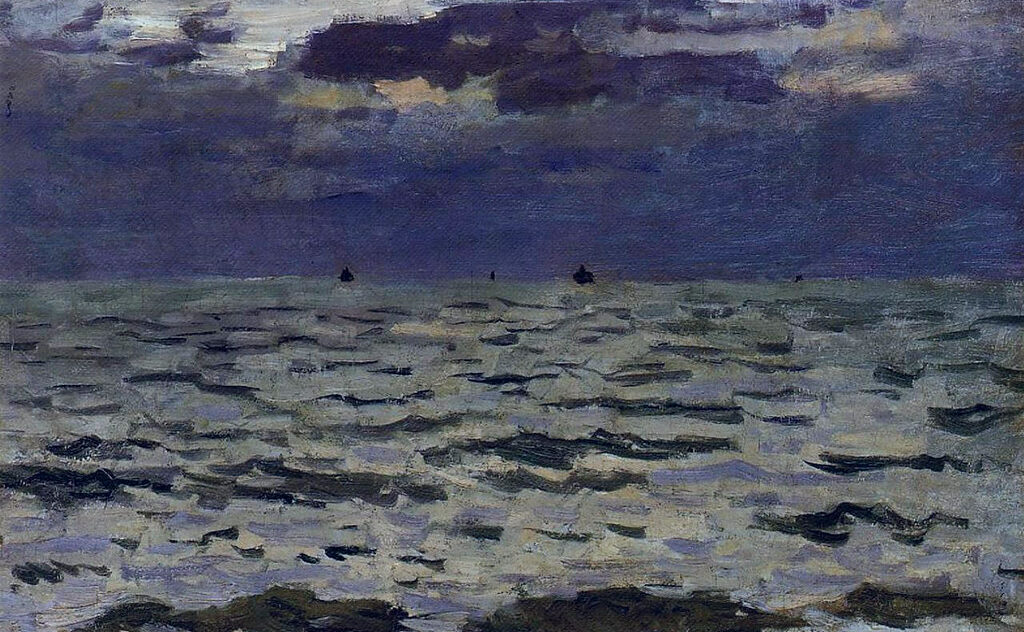

The waters closed so completely over people. They had swallowed, in succession, everyone I had ever come close to loving….People sank, the surface smoothed over; still you were left with their rippling reflections, glancing at you whenever light struck the water. As a child I’d assumed that Granny Astrid had not loved her lost children. She had not seemed to love anyone, until my father died and she gave up wanting to live. Later I realized how little I had ever understood or wanted to understand. If the reflections pained you, you looked away from the water. And if you were an island, surrounded on all sides? Still you tried to look away.

Whether in memories or in the mark of grace—as in the mark of baptism in Greene’s The End of the Affair—much depends on how we respond to the ramifications of our choices and, even more acutely, of the realities we could never choose on our own. Thomas’s novel suggests that those who would answer these difficult vocations well must learn to look through the pain and see the light shining through.