What you’ve done becomes the judge of what you’re going to do—especially in other people’s minds. When you’re traveling, you are what you are right there and then. People don’t have your past to hold against you. No yesterdays on the road.

William Least Heat Moon

The sunlight was fading into a glorious, breezy, late summer evening as my parents’ aging Toyota sedan disappeared around the corner.

I stood there for a moment, then walked behind the building, kicked my sandals off, and laid down in the grass. For 10 minutes I lay there, holding the empty pillowcase I would drool on over the next four years, the empty pillowcase which had fallen out of a box and my mom found at the last moment. I lay staring at the painted sky and felt the cool grass between my toes. I held that pillowcase in my hands and considered for a moment the weight and glory of what was before me.

Throughout my life to this point, I was defined, propelled, and constrained by my own history and baggage. There was never a point in my 18 years where I wasn’t judged on the basis of some part of my history. There was never a point in those 18 years where I wasn’t known.

Frankly, I was tired of being the me I had become and thrilled by the imagined opportunity to try something new.

I was in the midst of one of those rare moments in life where you start from close to zero. No familiarity, no job titles to seed division. New people, new perspective, and an opportunity—in extremely close-quarters with 35 complete strangers—for personal re-invention.

In this way, living on a freshmen hall is more than a bit like travel at its best. The isolation and disconnection from normalcy can be so intense and deep that it forces new relationships to take hold and new identities to emerge. In a very real sense, college was my first opportunity for this kind of formative travel.

When I walk up those stairs, I get to choose for myself how I will interact, how people will perceive me, who I will become.

And perhaps this is a choice we make every day. As holocaust survivor Victor Frankl said, “Man does not simply exist but always decides what his existence will be, what he will become in the next moment.”

It wasn’t that I wanted to be someone else, someone fake or superficial. Rather, I wanted to exist as a truer version of myself, someone freer, less constrained, more authentic.

I wanted to make great friends, and have magnificent adventures, and fall in love, and learn important things, and stay up too late, and play pranks, and get into trouble, but mostly escape unscathed. Above all, I was ready to have fun, lots and lots of fun for four years pretty much without ceasing and then leave this place changed and ready to be invisible and disconnected again in a new place, but with a better sense of who I was.

And so, I would.

In my enthusiasm, I forgot my sandals lying in the grass. I walked up those stairs, with earth still in my toes, holding the empty pillowcase that had fallen out of a box which my mom found at the last moment, and started a new life.

It was a full blown lake-effect blizzard, and we were out in the thick of it. My new crew had spent the better part of the frigid evening on the dark, snow-blanketed lawn outside our dorm where, just a few months earlier, I’d lain with my feet in the grass and forgotten my sandals.

In those hours, we fashioned the finest makeshift dual-chamber igloo Western Pennsylvania had ever seen. The rest of the night we sat huddled inside, rejoicing at our creation and the good fortune of having found each other.

We were ecstatic with the possibilities of our own creative potential together. In those months of chaos and late-night adventures and a little bit of stressful studying, perhaps we were bonded by more than our love for mischief.

For the first time in any of our lives, we were living in the midst of a community of our own design. It wasn’t the most perfect community. It didn’t give us all the answers, and it certainly wasn’t a model you could re-create everywhere or even somewhere else. It was particular to our situation and peculiar in all the ways each of us were.

Though we were all, in our own ways, living as individuals disconnected from our past, we were also part of building something beautiful and rich and complexly rooted in our own unique stories as much as in our common one.

Our hall was like the modern Church in that way, I think. The Church is not some abstract ideal. It is not mere piety and holiness and perfected justice and Christ fully embodied on earth. Church, real Church, is the Church before us. This Church is present with us, the real people who call themselves by that name with all their problems and hang-ups. And it is amidst this broken, imperfect, striving, peculiar human Church that we find our compass, our authentic purpose in this life.

It was amidst this Church of sorts, this community, where I stumbled upon a growing ability to think deeply for myself and, through those thoughts, to learn about and love myself in spite of my brokenness. It was within this community where I learned—more slowly, more clumsily—to listen and learn from others, to hurt with them, and to grow with them in the tender moments where their journey intersected with my own. It was in my search for freedom and dislocation from my past that I stumbled into the presence of this community of people who shared certain things in common.

I will not suggest that all of these things were good and holy, but some of them were, and whatever it was that united us for those glorious months was real and powerful, at least for a time.

Driving back to school after spring break, I was completely beside myself with anticipation for what was to come.

Heroically, stupidly, whatever you want to call it, getting a good story was at the very core of our identity as a group. The written warnings from Campus Safety, the close encounters with actual law enforcement, the generally harmless menace we were becoming to the entire campus was all for the sake of the story.

In light of such an obviously timeless bond, I was certain our destiny was sealed. We would spend the next four years plotting a course of adventures and mishaps unlike any the school had seen. We would graduate by the skin of our teeth, and the school would enact a policy barring us or any of our offspring from ever again stepping foot on campus. Most importantly, we would be together.

But I was wrong.

Just like all communities not built and continuously reaffirmed on the basis of something truly lasting, we fell apart. For some of us, school took precedent. For others, girlfriends came into the picture and created divides. Others grew tired of the endless seeking and striving for the next great story or felt more comfortable aligning themselves with more established, known groups across campus.

For one reason or another, we gradually drifted apart. These things happen, I know. But that year was special. I still sometimes think nostalgically about what might have been.

Today, I can claim but a single friend from that original group, and how that one stuck is an unlikely story I’ll save for later.

I pray it doesn’t end the same way for our Church of “resident aliens” as Stanley Hauerwas calls us in his eponymous classic. For this Church is formed by something more core, more vital, than fun-filled nights in a Western Pennsylvania corn field or moments of emotive self-recognition huddled inside a deathtrap igloo.

Yet as a Church, as a people, we don’t necessarily behave that way. Indeed, many of us have gone far off base in our attempts to become the heroes of our own stories. We strive and fight and look for opportunities to re-make a world in our image, one in which we can take pride. We go looking for entertaining mischief or try to align ourselves with groups and systems we think might set us free, that might serve as substitutes for those things we crave most deeply—connection, love, belonging, truth.

But fortunately enough for me—and for us as a Church—we don’t have to be the heroes of our own story. We don’t have to save ourselves.

What we have first of all is not a heroic people, but a heroic God who refuses to abandon His creation, a God who keeps coming back, picking up the pieces, and continuing the story.”

– Stanley Hauerwas

—

The above essay is an excerpt from Jacob Sims’ new book, Wanderlost, published this week.

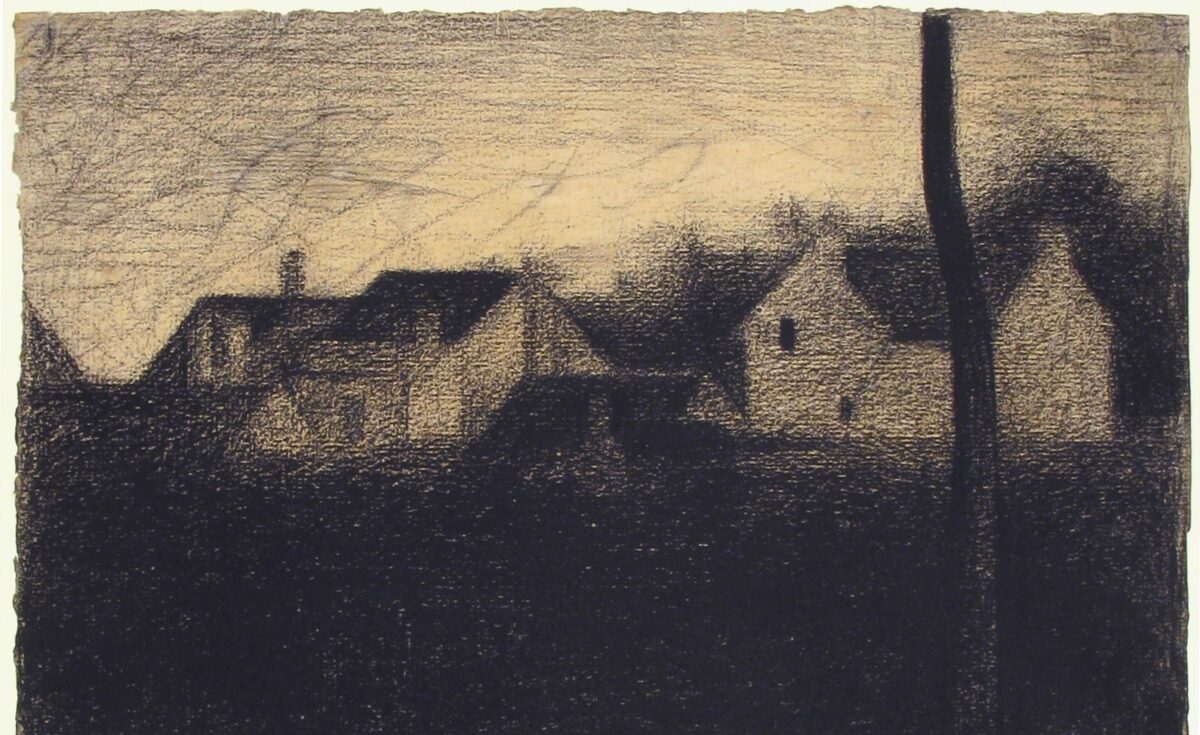

Image Credit: Georges Seurat, “Landscape with Houses” (1881) via The Metropolitan Museum of Art.