Peruse the typical church bulletin and you are likely to find a menu of Bible studies, programs, and retreats. Often these materials and events are produced by handful of large publishers, who not only publish books but all kinds of resources for Christian ministry—everything from welcome packets to vacation Bible school programs. Many congregations shop around to find the resources that meet the specific needs of various demographics. Both congregations and publishers seem to benefit from this arrangement. Those who work in ministry are often overworked and underpaid—lacking the time and energy to create their own materials. Publishers work with experts to create thoughtful and engaging content. This symbiotic relationship between congregations and publishers could be called the ministry-industrial complex. Ministries rely on resources from publishers, and publishers are happy to profit from providing congregations with content tailored to meet their members’ needs and preferences.

While this relationship appears to be mutually enriching, it produces several unintended consequences—one being that it sets a professional standard for ministries. Churches who develop their own program, retreat, or Bible study may appear to be falling behind compared to the kinds of resources produced by teams of people with expertise in communications, graphic design, and video production. As a result, congregations face pressure to provide similarly attractive religious products to retain and attract members. Doing so encourages them to outsource some of their work, turning them into administrators of branded resources. Vatican II touted full participation of the laity, and many Protestants profess a “priesthood of all believers,” but when ministry leaders begin a new program, they might find themselves turning first to the latest publisher’s catalogue rather than the church directory.

The ministry-industrial complex encourages congregations to shop around for the resources that will spark increased attendance in weekly programs and on Sunday morning. It also fosters consumerism among church members, who learn to become consumers of religious products rather than people with duties and obligations in a membership. As consumers, the people in the pews become disposed to participate in programs only when they are packaged to fit their personal preferences. They might also develop a relatively low opinion of church ministry in general, seeing it as a collection of resources that they can draw upon for therapeutic reasons. Such consumers may have no problem declining all ministry participation, because saying “no” to the perpetual call to “be involved” merely implies that the current ministry offerings do not fit their needs. An invitation to be involved in ministry would be seen in a whole different light, however, if it came from a fellow member of the congregation—inviting them not to another short-term, mass-produced program but to share in the journey of faith. As Pope Paul VI noted, “Modern man listens more willingly to witnesses than to teachers,” even if those teachers are experts at producing engaging content.

Perhaps the most detrimental unintended consequence of the ministry-industrial complex is its ability to warp how congregations and their members imagine formation itself. The ministry-industrial complex excels at providing resources that inform and inspire, but such programming should not be conflated with formation into the Christian life. Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger warned, “There can be people who are engaged uninterruptedly in the activities of Church associations and yet are not Christians.” Elsewhere he notes, “The saints were all people of imagination, not functionaries of apparatuses.” True formation should extend beyond informing the mind and inspiring the heart—in order to cultivate the necessary virtues of the Christian life through sustained, embodied, practices in community. Weekly programs are limited in their ability to foster true transformation, especially when they are designed to provide the kind of information and inspiration that sells.

Criticizing the ministry-industrial complex does not mean professional resources have no place in ministry. It is not so much their use as their guiding role in congregational life that prevents churches from prioritizing deeper formation. Information and inspiration are good, but congregations must recognize their insufficiency to foster deep and sustained transformation—and must not confuse tools meant to inform and inspire with formation itself. Polished programs and resources may appear to be of a higher quality than what ministers and church members can provide themselves, but like St. Paul we should not overemphasize “lofty words or wisdom,” because the Christian message is not meant to be “plausible [in] words of wisdom, but in demonstration of the Spirit and of power, that your faith might not rest in the wisdom of men but in the power of God” (1 Cor 2:1; 4-5). An overreliance on such tools leads congregations further toward a therapeutic approach to ministry, diverting them from the kind of deep formation necessary to sustain the Christian faith in our secular age.

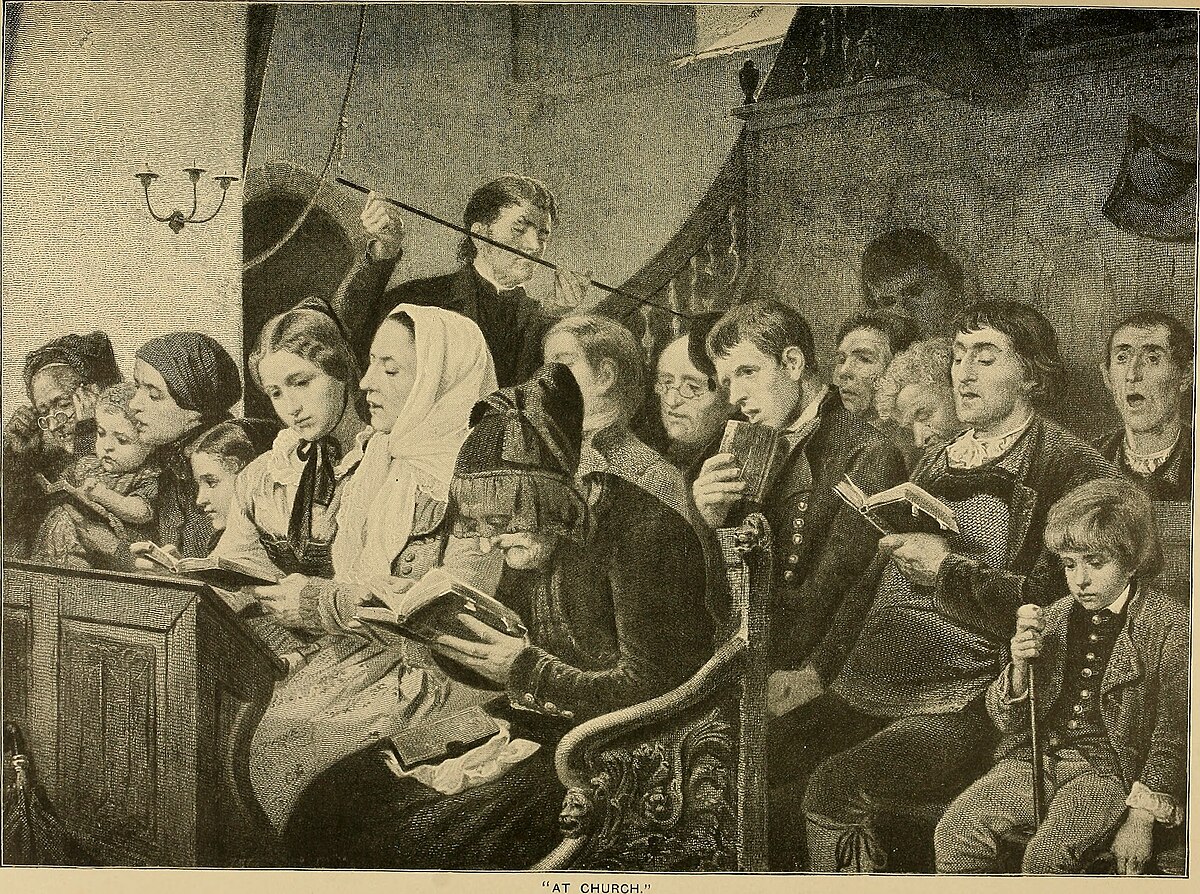

Image credit: “At Church” by Benjamin Vautier via Wikimedia Commons

7 comments

Dan Grubbs

I was excited to finally read someone else brave enough to address the troubles with using extra-biblical resources for the disciplining of a local church body. Yes there will be thousands of readers who will say they have used books and other published items written my men or women and they were fine, maybe they even grew spiritually. But, I’d boldly say they are the exception to the rule. Millions of other “churchgoers” are sitting stagnant and easily led astray by man-made content.

I taught Sunday school to college students and adults in two local churches for nearly 15 years and can relay my experience and opinion briefly here.

In addition to the challenges these materials may bring to the local body already outlined in this article, I have observed there is less koinonia when using extra-biblical materials. This is a shame because one of the great outcries for why people don’t attend church each week is the lack of connection or koinonia. This topic alone is worth gallons of ink.

I’ll also point out that churches using these materials end up with an auditorium, sanctuary, or classroom full of people who are less able to rightly handle the Word of God themselves. If scripture is not taught, how in the world can we expect people to be knowledgeable about scripture, deepen their relationship with God, and thus be able to make application in their lives? If competent exposition of the Word of God does not take place from the pulpit, lectern or the Sunday school class, we cannot expect the people to be able to make it a part of living their life. My experience is they are easily drawn to other teachings that are not of God.

Personally, I also can’t have faith in something I know is not a work of the Lord through the author. No matter the editorial policies of the publishing house, you cannot be guaranteed the work is from the Spirit’s leading. This is extremely dangerous for the individual and deadly for a church body. This is in contrast with the Bible, of which you can be fully assured it is a work of God and sufficient to train all of us (2 Tim. 3).

I would go on and on about this, but I hope the point is clear … the Bible is sufficient for discipline believers, whether they are babes in Christ or are 60 years in the faith.

Rob G

It does not seem to me that the author is against the use of such aids, but rather the overreliance on them. I’d argue that these things are in fact necessary, or else what you’ll get from the pulpit or lectern is merely the pastor’s or teacher’s individual expository whim, which may or may not line up with what Scripture “actually teaches.”

Dan Grubbs

That always has been the danger long before there were extra-biblical content. Nothing has changed since the days Paul was correcting Asian and Roman churches from false teachers and bad doctrine. It has been my experience that when we rely on aids, we reduce our ability to rightly handle the Word of God. There are those with the gift of teaching and preaching, but we are all called to rely on the Holy Spirit to be our scriptural interpreter. That’s not just a nice saying, that’s a doctrinal fact of the believer’s life.

Rob G

There was always extra-Biblical content, not least in the period between the Resurrection and the circulation of the earliest Epistles and Gospels. Some of that content made it into the NT, some of it didn’t. But it was always there, and the pastors and teachers didn’t simply ignore it. The history of Scriptural interpretation shows this.

Dan Grubbs

Not discipline, sorry for the typo, didn’t proof.

Martin

“The saints were all people of imagination, not functionaries of apparatuses.”

A great quote. Can someone explain how it applies to the Vautier painting that appears above this cogent essay? Is the minister trying to disturb a man engaged in reverie so that he conforms to the pace of everyone else’s prayers?

Dave Schmitt

To me it looks like he is passing the bag for the offering. But doing so while the church is singing would still be diusruptive.

Comments are closed.