This year, FPR hosted a student essay contest. We received some excellent submissions, and we’re running the top three essays this week, timed to coincide with Wendell Berry’s 91st birthday. Here is the runner-up essay.

Since graduating high school, I have told people that I specialize in impracticality. I love to read, write, sketch, sculpt, play piano, act, and birdwatch—all occupations thirsty for time and tending to flatten rather than fill my wallet. I suspect that some might view me as a spritely ignoramus, dancing through cumulous visions, and fated to someday be cracked upside the head with the 9-iron of reality. But Wendell Berry’s essay “In Defense of Literacy” offers a fresh angle on the common use of the term “practical,” defining it as “whatever will most predictably and most quickly make a profit.” He then proceeds to assess two staples of practicality: predictability and speed. These dual malefactors threaten the integrity of our language which impairs our literature and ultimately debilitates enriched lives.

Berry argues that language and literature cannot be predicted because they “are always about something else.” Whether because of indecision or conflicting interests, I chose to study English partially because it allowed me to avoid the choice of a major. The study of literature opens avenues of learning into everything. Conversely, when we lose our ability to handle words, we lose our connections to history, philosophy, political science, geography, culinary arts, conservation, biology, and any other meaningful study. In a recent address at Grove City College, Andrew Peterson said that he used to take walks in the woods, but now he walks beneath poplars and oaks, sycamores and redbuds. Learning the vocabulary of a thing draws it into a realm of awareness and conversation. This endeavor also demonstrates care for the thing itself. Like Peterson, I used to watch birds on the feeder. Now I watch nuthatches and woodpeckers, orioles and chickadees. I hear the songs of American robins, Eastern peewees, and Carolina wrens instead of noise from a great generalized lump called “birds.” It is easy, when aiming at a calculated outcome, to mow over particulars which might interrupt or distract from the frictionless turning of the screw. As the comfort of predictability becomes paramount, language and accents suffer the same universalization. In Travels with Charlie, John Steinbeck laments the omen of store-bought bread, saying, “Just as our bread, mixed and baked, packaged and sold without benefit of accident or human frailty, is uniformly good and uniformly tasteless, so will our speech become one speech.” Literacy anchors us to our surroundings and our heritage. It acquaints us with the particulars and holds us in the web of relations. As Berry writes, “Without it, we are adrift in the present, in the wreckage of yesterday, in the nightmare of tomorrow.”

Speed is the second factor that Berry addresses in his brilliant defense. Our society craves instant gratification. This is evidenced by the increasing number of online orders, subscriptions to digital entertainment platforms, and the battalions of fast-food restaurants crowding every interstate exit, their red and yellow standards bristling above the tree lines. So it is with words. We gobble up and spit out what is cheapest, fastest, and most familiar; using AI overviews, texting acronyms, and safe turns of teenage phrase. Our chopped, 21st-century English hobbles along with the aid of peg-legs and plastic crutches, braced by cheap adverbs like “literally,” “actually,” and “honestly.” I spent a very brief stint working at a daycare with a young woman who started every single sentence by saying “to be honest.” So consistent was her repetition that I believed without this opening phrase, she was either lying or mute. But we need our fillers, exclamation points, profanity, and adverbs to express the intensity of our thoughts since we have removed sincerity from the simple yes and no. Our yeas are no longer yeas and our nays no longer nays. Falsity subjects the most basic statements to lexical decay. In his book, Ten Ways to Destroy the Imagination of Your Child, Anthony Esolen’s perverted narrator promotes dishonest slurring of language: love into sex, fairytales into politics, boys into girls, men into women, adults into children. This mash of neutered words is promoted in today’s classrooms—you can be anything you want to be and why not? Any word can be redefined by its user. As Berry observes, businessmen and politicians also use this post-modern sophistry, breaking words from their meanings to achieve an immediate effect. As with most normalized evil, this twisted use of language is highly contagious. It is a frightening thought that verbal husks may become the basis of our promises and our prayers. Fast and flimsy words are superficial. There is no substance in them that allows for the planting of seeds.

A plant needs roots before it can grow. Berry recognizes literature as the “roots and resources of a language.” Apart from mosses and tillandsia, plants cannot live without the work of what is buried. Similarly, a language must have literature. A “lively” language, as Berry calls it, is informed by its roots. Literature retains our humanity. It gives life to the living and the dead. The literary present is a beautiful thing, drawing the bygone into the here and now. Dr. Michael Rawl says, “We must have stories to understand, discern, and communicate our experiences.” Alasdair MacIntyre writes, “I cannot tell you what I am going to do until I can tell you the story or stories that I am part of.” Many great works of literature are monuments to us, obelisks and reservoirs to which we can return again and again over the course of a lifetime. At the beginning of Life Is a Miracle, Berry writes, “Human hope may always have resided in our ability, in time of need, to return to our cultural landmarks and reorient ourselves.” In Andy Catlett: Early Travels, the young narrator returns repeatedly to The Boy’s King Arthur. Wendell Berry claims King Lear as a personal “principal landmark.” Although I understand the value of inhabiting a single place for the long haul, that was never an option for me as a child. But I cannot pretend to lament my ambulatory upbringing. I am thankful for the life that I have had, collecting pieces of Tennessee, Kentucky, North Carolina, California, Ohio, Arizona, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. In a way, this has made literacy even more precious; the stories never change.

Jayber Crow learns to recognize Port William by the sky. In a way, children can learn to recognize Narnia, the Trojan shores, the Hundred Acre Woods, and the banks of Plum Creek by a single sentence.

Jayber Crow learns to recognize Port William by the sky. In a way, children can learn to recognize Narnia, the Trojan shores, the Hundred Acre Woods, and the banks of Plum Creek by a single sentence. Wordsworth believes that if nothing else, a child who reads will learn the invaluable trait of forgetting himself. Literacy nurtures an appreciation of individuality that is not egocentric. C. S. Lewis safeguards against a stagnant, selfish, and purely contemporary diet, saying, “The only palliative is to keep the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds, and this can be done only by reading old books.” To keep ourselves and our language rooted, we must continue to revisit the classics—the books which testify to what life was, is, and should be.

Attending to lasting, priceless literature is not an exclusive practice. In his essay, Berry speaks to the false perception of the specialist; the only member of society who has earned the right to indulge in literature once couched in successful retirement. Whenever I am foolishly tempted to adopt the belief that art matters only to those straddling the peak of Maslow’s pyramid, I remember that Van Gogh bought paint instead of food. As Berry mentions in Standing by Words, “Culture has been reduced to art; art to the works of artists in museums, concert halls, and libraries, which are patronized by non-artists in their leisure time. Thus, both culture and art are divorced from work, from the everyday lives of most people, and from action” (87). Van Gogh is only a tessera in the age-old pattern of starving painters, musicians, and writers who understand that “practicality” has kicked them aside. And yet they continue to create. If a person feels they have something to share, they will desire literacy. To tell stories, impart wisdom, express emotion, sing praise, and ask forgiveness, we must have words.

My favorite response to “I’m majoring in English” came from a little old lady in Kentucky. We call her “Grandma Sue.” In my inveterate shame, I answered the typical follow-up question before she asked it: “I don’t know what I’m going to do with an English degree yet.” She looked at me with wrinkles linking her eyebrows, blinked twice, and said, “I don’t know what you’re going to do without it.” What will we do without it, without the ability to appropriately and accountably use words?

Earlier this month, I was walking alongside a meadow in the Shenandoah Valley when a handful of goldfinches erupted from the long grasses. My initial thoughts were of snitches, King Midas, and Frost’s “Nothing Gold Can Stay.” Though informed by literature, these sentiments snagged on connotations of vanity until I remembered Berry’s well-known poem, “The Peace of Wild Things.” In it, the speaker resists despair by watching a wood duck and a heron at the water’s edge:

…I come into the peace of wild things

who do not tax their lives with forethought

of grief. I come into the presence of still water.

And I feel above me the day-blind stars

waiting with their light. For a time

I rest in the grace of the world, and am free.

The wild things are untroubled by predictability or “forethought,” and the water does not speed but is still. Via literacy, this gem of literature has been shared with me and has given a far superior eloquence to a delight that I too understand in my own particular place. It is magic, I think, or something very like it. Without literacy, we will die apart, knowing no more than self. With literacy we can live, and share, and see together. Once a person skillfully handles language, he will read far more than words. Like Shakespeare’s banished Duke Senior, he will find “tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, sermons in stones, and good in everything.”

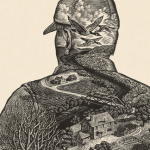

Image via hippopx.

3 comments

Rob G

Very fine piece. Nothing new, of course, but that’s rather the point. Instead we’re offered something old and valuable of which we often (constantly?) need to be reminded!

This is one I’ll be passing around.

Stephen Bartley

Really enjoyed this. A lovely bit of writing.

Colin Gillette

“This reads like someone who still remembers how to sharpen a pencil, and why it matters. Thoughtful, grounded, and just sharp enough to wake up a few dulled minds. Very much enjoyed hearing that literacy still matters to young adults. It will serve you well.