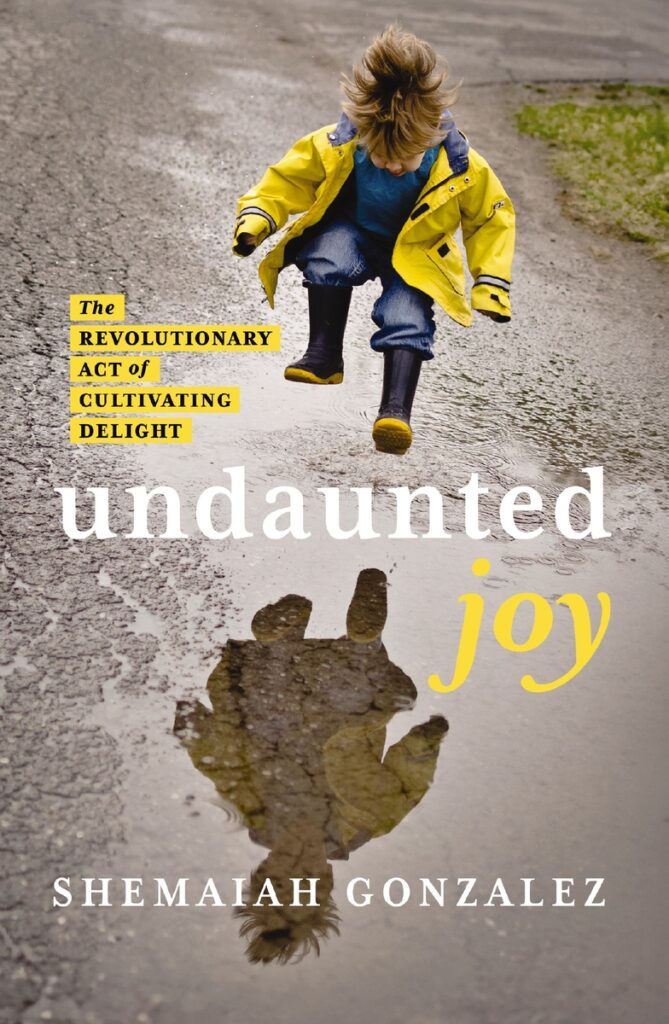

You might expect a book titled Undaunted Joy to open with a cheerful anecdote. Instead, Shemaiah Gonzalez surprises us with an unflinching—and, quite frankly, heart-wrenching—account of sorrow: “In 2005, my second year of marriage, my childhood best friend crawled into her bathtub, fully clothed, swallowed a bottle of pills, and then placed a plastic bag over her head to make certain she would succeed in what she set out to do.”

From the very start, then, it’s clear Undaunted Joy isn’t about ignoring pain or pretending hardships don’t exist. Gonzalez invites us into the reality of grief, loss, and anxiety, and then gently guides us toward a joy that doesn’t deny suffering but defiantly transcends it.

As I read her prose, I saw myself reflected in her pages. During the pandemic, I fell into a depression I couldn’t shake. Even when life resumed its normal patterns, I struggled to allow myself moments of lightness, haunted by the sense that joy was somehow inappropriate in a world so broken. Gonzalez names this tension that so many of us—especially Christians, perhaps especially Catholic Christians like Gonzalez and myself—often feel. She describes living in “survival mode” so long that joy became almost unimaginable. In some ways, her words felt like a hand extended in a dark room I remember once inhabiting:

“How do we build a life that allows us to be happy?” she asks. “You wouldn’t tell a child not to be happy, would you? Neither does our Father in heaven. He wants to give us good things.”

I paused reading these words, my whole being exhaling. Would I ever want my children to wonder if it was wrong to feel joy? Of course not! And neither does God. Jesus tells us in Scripture: “I came that they may have life and have it abundantly” (John 10:10). Yet we often live as if God prefers our desperation over our delight. Gonzalez reminds us that true Christian joy isn’t naive optimism; it’s faith lived in the full array of emotion.

The book’s 36 essays span a remarkable range, uncovering glimpses of joy in places both expected and wholly—and delightfully—surprising. Gonzalez writes of moments sacred and ordinary, her words a lantern in the dark: the quiet holiness of folding laundry, the simple wonder of a drive-through car wash, the comforting ritual of morning coffee, or unexpected encounters with beauty in art. She finds joy in fleeting marvels like sunsets, birthdays, and musical theater, as well as in the aching spaces of grief and anxiety. This broad sweep—from the mundane to the mysterious—reminds us that joy is not reserved for mountaintops but scattered like seeds throughout daily life, waiting to be noticed and received as grace. If, like Emily Dickinson, we go out with our lanterns searching for ourselves, Gonzalez helps light the path back to joy.

One of my favorite essays opens the collection, and it centers on a simple yet profound subject. Titled “Of Naps,” it begins with Gonzalez writing:

Naps are my prayer, to give up my will; for God to reset me, my intensity, my heart, my spirit; to redirect me to his will. To redirect my life by drift.

In this reflection, she references Wendell Berry’s Sabbath poems, which celebrate rest as essential rather than indulgent. As someone who has long appreciated Berry’s work, I was struck by how Gonzalez draws on his vision of Sabbath: Berry writes, “The mind that comes to rest is tended / in ways it cannot intend,” a reminder that Sabbath is where we stop striving and remember our lives are held by grace. Gonzalez’s opening essay invites us to see even a nap as a sacramental act—an opportunity to pause, reset, and remember that God, not our effort, sustains the world.

Another standout piece centers on Costco, a place Gonzalez and I both love. For our family, going there on Sundays is almost as much a ritual as attending Mass. Gonzalez delights in its hum of abundance and its “panorama of humanity”: She shares how she makes it a point to greet everyone she sees. This simple practice of seeing and acknowledging others reminded me of Jesus’ radical attentiveness—how he noticed the woman who touched his cloak (Mark 5:30-34) or paused for Bartimaeus when others tried to quiet him (Mark 10:46-52). Such small, consistent acts of seeing can help weave our communities back together.

Like Doyle, Gonzalez refuses to separate the sacred from the everyday. She writes with the warmth of a friend and the keen eye of a poet, revealing that God delights in the details of our lives—and invites us to do the same.

Throughout, Gonzalez’s essays reminded me of Brian Doyle, the late Catholic writer whose tender, humorous reflections revealed glimpses of the divine in even the most mundane details. Like Doyle, Gonzalez refuses to separate the sacred from the everyday. She writes with the warmth of a friend and the keen eye of a poet, revealing that God delights in the details of our lives—and invites us to do the same.

As a nineteenth-century girls’ series scholar, the chapter that most captured my heart is the final one, which reclaims Pollyanna’s “glad game.” Too often, people use “Pollyanna” as shorthand for childish naivety. But in Eleanor Porter’s 1913 novel, the glad game is a spiritual discipline: when life disappoints, Pollyanna hunts for something—anything—to be glad about. When she receives crutches instead of a doll, she’s “glad” she doesn’t need them. When neighbors rebuff her, Pollyanna looks for ways to bless them instead. Her refusal to sink into bitterness transforms her whole town.

Gonzalez writes:

Pollyanna showed a town not to be afraid of themselves or each other. She guided an entire community out of victimhood and taught grown-ups that gratitude is necessary for living a joy-filled life. And in all of this, she taught herself resilience.

This, I realized, is exactly what Gonzalez does in Undaunted Joy, too. Like Pollyanna, she teaches readers to find small reasons for gratitude. Her essays are gentle guides for spotting glimmers of grace, especially in life’s shadows. Rather than deny the world’s brokenness, she equips us to resist it by noticing beauty, giving thanks, and choosing hope.

In a culture where cynicism is easy and often rewarded, Gonzalez’s book is a courageous call to play the glad game. Yet she never offers it glibly. She acknowledges the deep pain so many carry, especially after years of collective grief, personal losses, and ongoing uncertainty. Still, she points to joy not as an escape but as a practice: the daily, determined choice Paul described when he wrote, “Rejoice in the Lord always. I will say it again: Rejoice!” (Philippians 4:4).

As I finished Undaunted Joy, I found myself reflecting on how often I’ve thought gratitude must wait until life is tidy and perfect. Gonzalez’s writing reminded me that perfection is a mirage; joy belongs to those who dare to claim it in the middle of their mess. And isn’t that the very heart of the Gospel? God doesn’t promise a life without suffering—he promises to be with us in it, offering peace that “surpasses all understanding” (Philippians 4:7).

Reading Undaunted Joy felt like a long, heartfelt conversation with a friend who has been through the worst and still finds ways to laugh. Gonzalez’s humor, honesty, and faith infuse every page. Her essays feel like invitations to look for joy—at the kitchen table, in the carpool line, or even in the frozen food section of Costco.

Gonzalez’s book arrives at a moment when so many feel daunted and are searching for a new way to find hope. It isn’t a self-help manual or a collection of easy platitudes. It’s a testimony: a woman who has endured heartbreak, asked God hard questions, and learned to laugh again—and now wants to share that hard-won joy with readers she clearly holds dear. In this way, Undaunted Joy becomes its own glad game, played page after page. It invites us to seek God’s goodness and remember, as Gerard Manley Hopkins reminds us, that “the world is charged with the grandeur of God”—and joy is how we join in that praise.

Image Credit: Watanabe Seitei, “Sparrows Flying” (1887) via The MET.