Every generation has had among its number those who predicted the imminent end of the world, and every prophet of doom up until now has been mistaken. But before we dismiss the next prophet of doom like the boy who cried wolf, we would be wise take a moment to read the times. History has swerved cataclysmically before, and one could argue few generations have faced such numerous, volatile, and severe crises as ours: economic stagnation and rising inflation, biosystems breakdown, rampant habitat loss, climatic instability, raging culture wars, the very real threat of civil wars in the West, the continued march of the Machine—the list goes on. And though some say the economy and technological innovation will come to our rescue, the AI bubbled, debt-loaded, energetically ravenous, and increasingly unstable state of our global economy makes it an awfully perilous system in which to put our trust and hope.

The severe poly crisis confronting us has led a growing number of political, scientific, and cultural commentators to predict, with ever-increasing confidence, that the end of the world as we know it is approaching. The earth can no longer continue to sustain the inflated, energy-hungry, earth-despoiling weight of neo-liberalism, modern industrialisation, and the accumulated sum of all our mass consumeristic desires. An almighty collapse is brewing on the horizon.

What hope do we have in the face of such looming catastrophes? How can we safely navigate the coming uncertainty? And how do we best position ourselves to survive and even thrive amid the forecasted storms? These are the among the most urgent and prescient questions we could ask ourselves at this time. Thankfully, we agrarians have a wide range of thinkers numbered among us who have been pondering such questions for some time, notably Paul Kingsnorth and those from the Doomer Optimism tribe. And though we can’t be sure that we will see civilizational collapse in our lifetimes, we would be wise to heed their warnings and follow their sound advice.

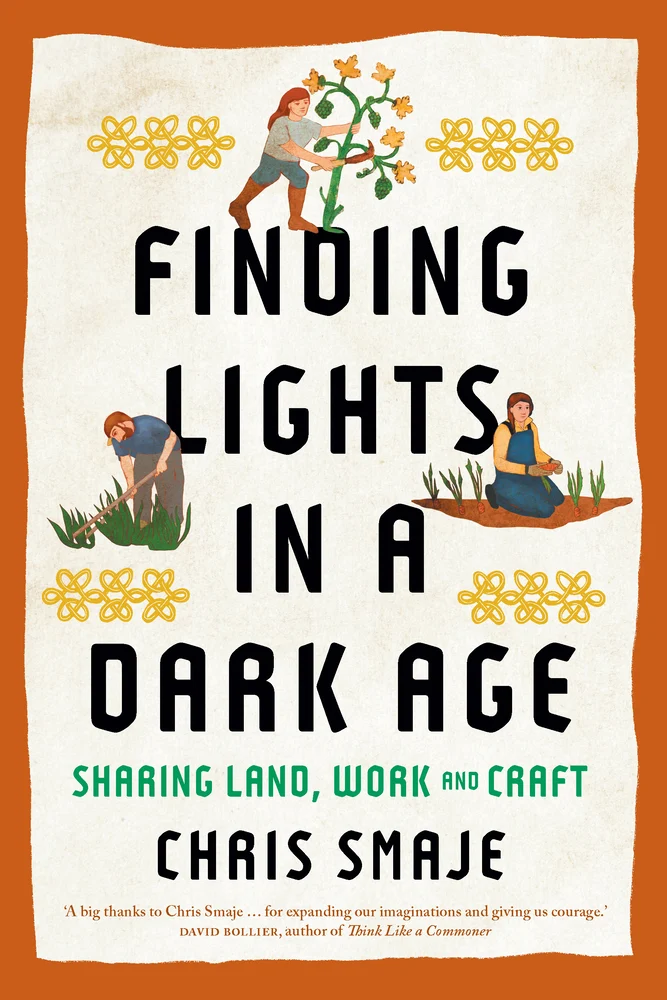

Another individual we would be wise to listen to is Chris Smaje, one of the few remaining advocates for agrarianism left in the UK, and someone who practices what he preaches on his small farm (if the authorities will allow him to call it that!) in the south of England. Chris has been predicting a collapse of industrial-style civilization for some time, and in his latest book, Finding Lights in a Dark Age, he has become surer of his convictions. In his words, the “business-as-usual” modernist world of industrialisation and neo-liberalism is a “world coming to an end from its own contradictions, pollutions and excess accumulations. It can’t be patched up by any of its existing mainstream technologies–political technologies, economic technologies and material or engineering ones.”

Such a collapse of the world as we know it will inevitably be catastrophic, immensely painful, and violent for many. But amidst the chaos, Chris argues, a golden opportunity for us agrarians may arise. The collapse of the business-as-usual world—which has been the chief opponent and great inhibitor of agrarianism—creates an environment where agrarianism can position itself the best means to feed, clothe, and house people, and as the optimum pathway for conviviality and flourishing in the chaotic new world. In fact, Chris is adamant that it may only be through chaos and collapse that widespread agrarian localist communities are enabled to emerge and thrive.

But alongside recognising that there may be an approaching golden opportunity for agrarianism, Chris also draws our attention to the urgency of the challenges ahead and the immense amount of work still to be done in order to build up the localised agrarian systems necessary to weather the coming storms. It is in order to address these urgent priorities that Chris has written this book, which could be described as a guidebook (or a guiding light) to navigate the “dark ages” ahead and to journey toward localist agrarian flourishing.

Though the future may indeed be dark, this book is far from all doom and gloom. As Chris notes, when we look at past dark ages, it is evident they have not been unilaterally dark for everyone. Those who existed on the fringes of society have sometimes flourished (relatively speaking) during these times as the control, meddling, and surveillance of the centralised state waned. In fact, land in these fringe, or “raw,” societies became hot property as urban people moved back to the land to find security in their own agrarian production. Undoubtedly, the manual labour was backbreakingly hard, but life for the ordinary agrarian folk during these times was also punctuated by rich times for feasting and celebration and relative food security compared to the urban areas in turmoil.

It can be argued then, that the dark ages of the past were (with necessary caveats) the bright ages for both ruralism and agrarian localism. In Finding Lights in a Dark Age, Chris strongly suggests that this may also be the case in the dark ages of the future; which is a proposition that ought to hearten us Porchers and give us something to work towards.

It needs to be said, though, that this isn’t a book to explore agrarian localism from a practical and agricultural perspective. Chris has already tackled the theory and practice of agrarian localism in his previous book A Small Farm Future, and it might be wise to read that book before one tackles Finding Lights in a Dark Age. Rather, in Finding Lights, Chris utilises political, cultural, and social lenses to explore what social and political features are likely to define the agrarian localist communities that are able to thrive in the chaotic future of the new dark age, and what enabling conditions are necessary for their emergence.

The optimal communities Chris envisions are medium-sized, tight-knit-but-open communities of small farmers and craftsmen and women bound together by strong families, which, in turn, are deeply invested in the local land held under a mixture of both the commons and private occupation. Equally important are the political structures and frameworks these agrarian communities operate under, which Chris argues ought to be defined by distributed forms of power and politics characterised by civil republicanism, subsidiarity, and bottom-up local action and decision making. In short, agrarian populism. Finally, Chris is at pains to stress that the agrarian communities that will thrive in the dark ages must aim at communal flourishing based on localised production rather than profit accumulation-based aims that have characterised our neo-liberal states to this day.

In Chris’s vision of the future, the centralised state is likely to still exist and still flex its (weakened) muscles, and there is always the danger of the emergence of a tyrannical, authoritarian state in the times of chaos to come. However, under the “solar system” or “galactic model” of politics that Chris uses to imagine the future, the reach, power, and legitimacy of the state is likely to be greatly weakened and exists as a mere “empty shell” of its former glory unable to provide distant populations with the services they require and unable to extend costly control and surveillance over them. Local agrarian communities (planets) under their local power brokers thus will have significant autonomy to get on with the job at hand without undue influence or meddling from the centralized state (sun).

Power, though, is addictive and difficult to surrender. It will be interesting to see how successful future centralised states are in trying to hold on to their diminishing power, what strategies and means they use to achieve this, and how they react to communities who strive for greater autonomy. As Chris says, “while people need government, they don’t so much need The Government.” This reality might be a bitter pill for our respective Governments to swallow. Expect them to thrash out.

As would be supposed in any book on agrarianism, the importance of land is central to Chris’s thesis, especially its availability. Chris argues that contrary to prevailing developmental theories of progress such as neo-Malthusianism, we are almost certain to see a significant increase in demand for land for small-scale agricultural production, mirroring the “counter-civilizational” movements that have occurred repeatedly throughout history in times of crisis. History does indeed repeat itself. Thus, ensuring land is available for those who wish to use it productively is essential for a small farm, localist agrarian future. This is where a relatively land-rich country such as the USA might be at an advantage to land-scarce and heavily populated European nations in a time of civilisational turmoil, and this is a topic which deserves to be explored further.

Finally, for a book dealing with scenarios of the future, some might be surprised, as Chris himself has acknowledged, by the absence of discussion concerning AI, especially in light of how vocal both its developers and governments are as to how AI is going to fundamentally change the world. Though it would have been useful for Chris to have briefly considered how AI might shape the future before the dark ages arrive, one could view Chris’s neglect of AI as an implicit statement of its long term irrelevance. In a future where modern political and economic systems have broken down, energy infrastructure is unreliable, and energetic abundance is no longer possible, widespread AI will become an impossibility. Thus, those arguing that AI will be our savior are falling for a “promethean hero story” without basis and reality. Simply put, AI has little value if the dark ages do indeed come.

We would be much wiser, then, to focus on building up our agrarian infrastructure, skills, and knowledge rather than chasing the pipe dream of AI. In fact, those who already are focusing on improving their agrarian competencies are setting themselves up to be, in Chris’s words, the heroes of the future: the shining lights in the dark ages to come.

As I finished this book, I found myself both daunted by the future chaos and enthralled by the possibilities for agrarianism and conviviality that it presents. But severe challenges remain if Chris’s convivial vision is to be realised, most keenly, do our societies contain the necessary skills and willpower to transition quickly to agrarian localism, and will the necessary land become available? Chris is optimistic, and I wish I shared his optimism. But when I survey the nation (England) we both live in, all I see is that agrarianism is in disrepair, land in short supply, the state increasingly hostile to small farmers and ecological solutions, and the population suffering severely from nature-deficit disorder and an entrenched reluctance to get their hands dirty in the soil. Can such a society be mobilised to work and care for the land and forge tight-knit communities built on trust, shared work, and agrarian wisdom? I don’t know—but I hope so. However, this is certain: there is immense work to be done by us agrarians, both in developing our own practical agrarian skills and encouraging our neighbours to join us. This work must begin now.

But the real strength of this book is that we don’t need the motivation of future collapse in order to begin this work. The agrarian localist future, along with its attendant cultural habits and political and community structures, are systems we ought to be creating now—collapse or no collapse—simply because they are the most convivial and sustainable way of living on this earth and are the right things to do. However, the risk of civilisational collapse is real, and in such a world, agrarian localism is not only desirable, it is essential. All the more reason to urgently begin the work of building up sustainable and resilient agrarian localist communities across our nations, so that the places which we call home shine as bright lights no matter what darkness lies ahead.

Image via pexels.