Cedar Falls, IA. A modern combine resembles a monstrous contraption assembled in children’s dreams. This oversize roaring box wobbles out of machine sheds in September when Iowa corn and soybean fields are ripe and ready. A corn head latched onto the front of our red machine thrusts dinosaur-size, jagged scissor-teeth out from a prominent chin to chew up every single corn plant on our farm by snatching up most of each stalk above ground without harming the ear. Farmers still complete the job by hand in many countries, but they also use combines to harvest crops more quickly from industrial-sized fields. Riding as a passenger is a thrill for me every fall, a fascinating adventure like climbing the ladder to take a ringside seat on the edge of the world.

Almost everything changes after it goes through a combine. The corn head skids forward along the ground gobbling everything in its path. The growling mouth gulps 10-foot-tall corn plants, weeds, and even stray rocks while rabbits and field mice scamper away. It’s an impossible game to tally plants by the sixes or dozens to keep track while the machine chews through the field. Plants that stand six inches apart in parallel rows stretching out a half mile ahead are clipped six rows or more at a time horizontally across the head in front of us. Dozens of plants multiply into hundreds rapidly. Electronic meters that estimate bushels of shelled corn per acre flash like marquees, but the final yield numbers don’t count until the last plant is threshed.

Simultaneously, everything happens invisibly inside the roaring box. All we can see in the rearview mirrors are chopped plant parts blasted out an exit chute, flung in every direction by a spinning disk spreader. A giant metal tank open to the sky on top receives the cleaned corn or soybeans from the interior, as if the storage vessel is a private royal carriage that fills miraculously with millions of precious gold nuggets. Everything about a combine stretches my imagination–from the uncountable parts that clatter just so when all is well to the radio’s robotic voice broadcasting the regional weather in the sealed cab. It’s an amazing and incredible invention.

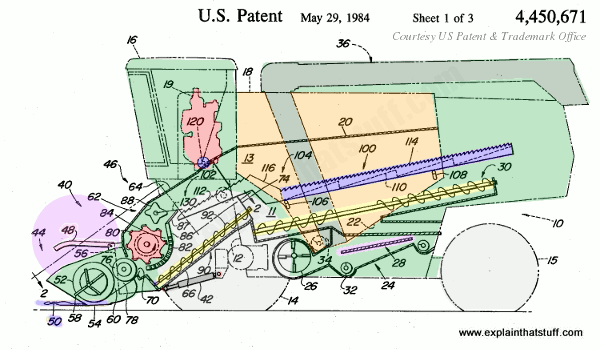

The word combine is pronounced like baseline or headline, with stress on the first syllable. They’re called combine harvesters because they unite nearly all harvesting tasks into a single machine. They cut the plant, isolate the seed head or ear, separate or thresh the seeds or kernels from the cob or husk, collect the seeds, and shred the plant residue through a straw chopper that discharges chaff onto the land in a way that’s adapted to spring planting the following season. Historians trace the invention cycle to a reaper in 1826 in Scotland, followed by an American design introduced in 1834 and pulled by horse, mule, or ox teams. By 1860, combine harvesters were commonly used on American farms. Since then, design features evolved into contemporary models that supersize what’s possible. Sixty-foot-wide bean platforms guided by automatic steering tease the limits of human peripheral vision.

Inventors and farmyard tinkerers across time contributed features throughout the machine, like Austrian American Oscar Zerk whose name is immortalized in a small metal grease fitting for lubricating mechanical joints. There can be 85 zerks on a single combine, maintained at 10-hour, 25-hour, 100-hour, or 300-hour intervals. Our area grows the equipment as much as the crops, including subsidiary manufacturers and supply chains that provide everything from graded bio-fuels to tractors with tracks to the tiniest microchip essential for operating most modern implements. Big shops, little shops, factories, multinationals, the labor and creativity of thousands of people across the world have a place in our fields.

The combine itself is a sophisticated network of complex electric, hydraulic, mechanical, fluid, static, and pressurized engineering systems that function interdependently. None can do the job alone; each is an essential contributor to the whole. Together, these components test how much a working person can supervise safely. When the driver turns the key, the diesel engine starts a sonic cascade that builds a range of distinct sounds, flashing lights, grinding noises, flowing fluids, whirring belts, slicing knives, pounding pistons, and automatic buzzers that reverberate like a lot of noise but really create a symphony of order. Beans pinging like hail against the windshield tell the driver to adjust the reel settings, one of many indicators a skilled operator tracks constantly and silently. Slight variations signal disorder and the whole system shuts down until whatever caused the problem can be reset, fixed, or replaced.

Rocks and fires are the biggest hazards during harvest. A rock plunking into the feeder house will clunk a danger signal in the driver’s brain. In the few seconds it takes to turn off the engine, the rock can tumble into the mechanical guts and cause real damage or even ruin the machine. Fires start inside where metal friction can spark a flame in the brittle plant matter. Swirling dust and plant debris, including the red husks or bees’ wings that shed off each corn kernel, cover the ground and anything parked nearby. The acrid odor of a scorched belt rings an emergency alarm in the operator’s mind since the machine or the field could catch fire.

Days of driving are mesmerizing and exhausting. Maneuvering the combine back and forth, east to west, west to east, or north to south and back north again, harvesting grain all day long and into the night has a relentless pace. My husband Harry compares fieldwork to watching a Bob Ross painting take shape, where each movement is a step toward an inevitable outcome. Our daily routine creates a rhythm for the long days, starting with equipment maintenance and refueling, fitting in meals, family responsibilities, and hauling grain to storage bins or the local co-op throughout the workday. Rainy weather is catch-up time where all activities focus on the single goal of getting back in the field.

Since many farmers plant during the same few weeks in the spring, most farmers’ fields are ready for harvest at the same time in the fall. Sheds across the county open up in late September as farmers prepare their tractors, combines, wagons, grain carts, and trucks that all take part in the final stages of the production cycle. Once harvesting begins, our world changes shape as each field is reduced to stubble after months of vibrant green growth in lush forests of corn plants dominating the landscape. Then a great silence descends on the neighborhood after all the equipment is cleaned and stored for the winter. Field work and hauling grain to sell will last until the ground freezes solid.

The immigrant origins of many agricultural communities can be traced by the stewardship practices, farm layout, and expressions that derive from other languages. Scandinavian and German families migrated to our area of Iowa in the 1830s. “Are you going, then?” our neighbor Arlene asked each spring when she and Fritz pulled in the driveway to chat about the start of planting. The red chaff released from corn kernels might be called red dogs in your area. They’re known as bees’ wings in ours. Some just call it the red dust that covers everything during harvest. Another Germanic expression retains its logic today: “You have to be crazy to farm” affirms the risks in a life devoted to agriculture.

When we finally park our combine in the shed, it feels like coming home after a satisfying journey that took six weeks at 3.5 miles an hour. We didn’t go very far–just back and forth hundreds of times across the same half-mile stretches of land. I honor the privilege of time spent on the jumpseat wandering through the corn and bean rows where I encounter an enthralling maze of big questions about agriculture, engineering, global food production, and how all these things channel through the ungainly boxes on wheels that harvest gold from our beautiful land.

Older machines may be traded or sold in an upgrade while some are repurposed for the annual combine demolition derby. Events like the derby can function as “an existential necessity,” according to one reporter, keeping towns afloat with a spectacle that beckons tourists from a wide region for a good time at the county fair. Folks pay $10 a head to see obsolete machines souped up for the contest stumble across the modified arena like headless gladiators that mock the expensive machines. It’s an improbable finish for a once-prized possession that was washed, waxed, buffed, and protected from scratches and overhanging trees along fence lines.

Engines sputter while slow-motion crashes draw shouts from the crowd. Judges call a tie when combatants stay stuck, the dented hulks pasted with old paint and decals immobilized and smothered in mud. Last year’s prize in Iowa’s largest combine derby, held in the next county over, offered $11,000. Winning the purse may not even cover the expenses of the team holed up in the machine shed all winter, but refurbishing an old favorite for next year’s battle brings people and skills together in new ways.

Will having seen the “major crunch” between Grim Reaper, Malt Muncher, Jimbo Smash, and Grain Digger promote a new investment in the culture of tomorrow’s agriculture? A ride in a fire engine still inspires children to dream of becoming firefighters. A fire engine is a big tank of water that holds a lot of social meaning, driven by people we call heroes who invite kids along for a ride. Most of those kids never become firefighters, but time spent cultivating the civic imagination is never wasted.

Likewise, we can offer appreciation for producers of all kinds, as well as to the field laborers, scientists, engineers, machinists, and factory workers all over the world who make today’s extraordinary agricultural production possible. Supportive efforts can steer this ingenious workforce toward better stewardship and environmental integrity by reclaiming that awe that life on the land should inspire.

Farming can seem anonymous in a drive-by glance from the highway. But the people driving the equipment or managing business on the farm are essential to our communities. Grandparents in their 80s who remember farming with their grandparents in the era of horses may take the helm in the combine these days with a grandchild next to them on the jumpseat. Adult children, relatives, and retired neighbors may spend a week or two pitching in with the harvest, a tradition that values shared labor. We need these stories and activities to motivate people to become engaged so there’s a future for all of us in farming.

1 comment

Sam

I didn’t know there was anybody left who had ever stuck a grease-gun on a zerk.

Comments are closed.