Front Royal, VA. In our first four years of marriage, while we were working on our history Ph.D. dissertations and starting our new jobs, my husband Chris and I moved five times, including overseas. When we finally bought a house in small-town Virginia, we decided: never again. Or at least, not for a good long while.

Moving is exhausting. I love a good adventure, but the process of getting to know a new place and culture can be difficult if you don’t stay long enough to really make friends. It was the not having friends part that was hard (well, that and the hanging pictures over and over. I hate hanging pictures!). When we moved to Virginia, I was determined to stay for long enough to really, finally, feel part of a community. I wanted people.

What I didn’t realize was that with the people came the land and, more specifically, what had once happened there.

My mother was a forest ranger, and I grew up barefoot and outside, so I already knew that landscapes, both natural and urban, were important to me. After college and before graduate school, I survived living in Los Angeles by taking long walks in the botanical gardens of the library where I worked. Later, while living in Paris after one of our five moves, I relied in the same way on the city streets, becoming an old-fashioned flâneur, a person who wanders the city and simply drinks it in. It was a marvelous antidote to the stress of writing my first dissertation chapter.

What I didn’t know was that my historian’s brain would have a different response to the Shenandoah Valley than to Paris or Los Angeles. In those places, even though I knew about some of the darker episodes of the local history, I focused on baguettes and botanicals, respectively, rather than Robespierre and riots. I let the happy side of my imagination loose in the architecture and the ivy, and I let the rest sleep.

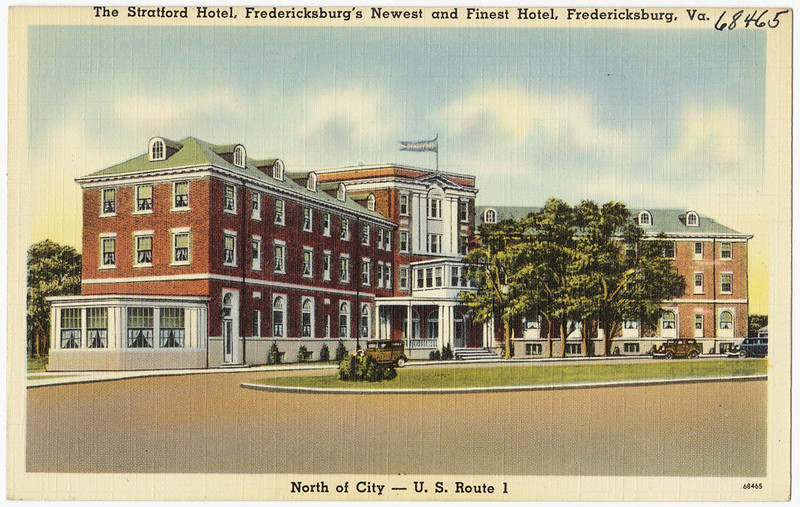

But in Virginia, my specialization in American history came back to haunt me. Driving around with my fussy baby finally asleep in the back of the car, I would suddenly see a street sign: “Fredericksburg, 90 miles.”

My heart would stop. I would grip the wheel. The air would spin for a moment, and I would almost throw up.

Do you know how many people died there?

It happened to me almost every day. Stonewall Jackson Highway? There stands Jackson like a stone wall! yelled my historical memory, recalling the rallying cry at First Bull Run/Manassas, and then I would sink into remembering the grueling nature of Jackson’s later death. And every time I saw a copse of trees, I would think, Who passed through there in 1863? And then I would think of the Battle of the Wilderness, and death amongst the trees and the fog.

I ate Chick-Fil-A next door to battlefields. The whole thing was just staggering.

With a name like Dixie (my mother was from the South, though no Confederate), I perhaps have had more reason to think deeply about the Civil War than many Americans. Thanks to a combination of late-19th-century mythologizing and 21st-century self-righteousness, most Americans today have little connection with the real Civil War, as opposed to the fake versions that public figures bastardize whenever it suits them.

By the real Civil War, I mean the blood. I mean the blood, and I mean the weeping, and the way the whole thing swept people up, willing or unwilling, like a great tornado, and spat them out again either naked or dead.

But living here, it’s real. It’s everywhere. It’s in the street names. It’s in the cemeteries. It’s in the nearby city of Winchester, which changed hands between Union and Confederacy seventy times between 1861 and 1865.

And when my friend had a precipitous labor and delivered her baby in her car on the side of the road, the war was even there, for crying out loud. Her husband had pulled the car over into the front yard of the farm where ended the Battle of Front Royal.

War is always, in the words of a D-Day veteran I know, deeply personal. I recently read the published wartime journals of Lucy Buck, a well-off young woman who lived on a prosperous farm in our town. The house still stands and is visible from the hilltop cemetery where Confederate artillery set up during the Battle of Front Royal and where many Johnny Rebs now lie buried. Lucy is a somewhat flighty girl at the beginning of the war, initially as much interested in gossip as in “the cause” and indignant about the commandeering of her father’s fenceposts by Union soldiers (they needed the wood). She is surprised to find a few “good” Yankees cross her path, and she upbraids them for being so ungentlemanly as to wear the blue. She saves her warmest smiles and all her loyalty for the boys in gray, and she cannot fathom why her family’s slaves all run away one night to behind Union lines.

But she grows more solemn with time. She must roll up her sleeves and learn to bake, now that the cook has disappeared. She becomes desperate for news about her brothers, cousins, and playmates, all now in harm’s way. Many of them do not come back and, due to the war’s drastic reduction of the young male population, she and her sisters will never be able to marry.

Her journal goes quiet for months as the South begins to lose. She is doing far harder work than baking biscuits now, as her father’s mill is destroyed, the crops are plundered, and she knows hunger in a way that, God willing, I never will.

Later I go to the public library to look for information about the formerly enslaved in our county. Lucy’s journals give the impression that the antebellum enslaved population was large, but today’s Warren County has an African American population of well under 10%. What could have happened?

What I learn is that there was a greater number of enslaved people in our area in the antebellum period than could be employed and that they formed a major percentage of the population. There was also a significant settlement of free black people in town. Where did all these people, enslaved and free, go? Did their descendants move North in the early twentieth century, as did so many impoverished African American Southerners? Or did the majority leave earlier, during the war itself, as did those who worked for the Bucks?

The answers are probably at the library or the historical society, and one day, when I have more steam and fewer loads of laundry to fold, I’ll take the time to find out.

But the long and short of it is, I live in the Shenandoah Valley, the valley of the shadow, and for me, there’s no getting away from the past. And this past is not simple. It’s not glorious. It is a tragedy, pure and simple, though I believe a necessary one. And I am glad that the names are here, and the copses of trees, and the graves, to make me remember. No other place can teach me just exactly what this place has to teach.

The Shenandoah Valley is also beautiful. I have come to love it deeply, and I hope to live a lengthy life here. I could write a much longer article than this one about the way my soul feels at rest in my adopted home. I live in a place of rolling hills, of the wildest of wildflowers, of the beauty of truth and of the bright light of life.

But isn’t that what life is? The light is more powerful than the darkness, but if we forget or, worse still, mischaracterize the darkness, how can we rightly value the light? The memory of pain has the power to protect our joy.

The land, the place, the names, the people; these are what connect us to today and to every past day. Let us remember them then, so that we may plead, in the words of antebellum composer Stephen Foster, “Hard times, come again no more.”

6 comments

David H Bain

Thanks for this piece, Dixie! As one of your former instructors, I saw all of the gifts seen on your work way back when! I share the sense of simultaneity in resonant, historic places–have since I was a grade schooler–and one so attuned can bump into reminders and other-worldly connections often in the historic Shenandoah Valley! Makes one’s head spin. Keep up the wonderful work, Dixie!

Dixie

Thank you, David! My time in Vermont, some of which you shared, also resounded with these echoes. I am sure you have seen the grave marker near the Cross-Country trail at Middlebury for the soldier who was killed by a falling tree while walking home from the Revolutionary War; there is such passion in the woods, the graves, the trails, the land. It is a joy to find that others notice it, too.

Jay Dillon

My sister Dixie Mae continues her publishing spree with the most moving and heartfelt essay I’ve ever read about reconciling a name like hers with a life lived among the bloody fields of Civil War history. Drop what you’re doing for this 5-minute read. It’ll put you and your heart in a beautiful place.

Dixie

Jay, I’m honored by your response to this piece. It has been a gift to experience a vibrant life in a place once characterized by so much pain. The landscape and the heart are both resilient, but we help no one when we forget too much.

Anna Maria Hatke

Dixie this is a beautiful honest piece. Your words captured our landscape of paradox, one that is both breathtakingly beautiful and also an inheritance of bloodshed, and names that have fallen out of memory, indigenous, enslaved, black, white. Transmuting that pain into authentic living is the challenge of our time. Thanks you for writing this!

Dixie

Thank you, Anna! You put this all so well. We have nothing to fear from allowing ourselves these kinds of realizations and emotions!

Comments are closed.