The new website you’re seeing now isn’t just a cosmetic tweak. Dan Beltechi, the craftsman behind Pilcrow, has rebuilt FPR’s virtual porch from the foundations up. Not only does it offer readers a better experience (particularly on mobile devices, where our old site had significant problems), but it is built on a much more elegant and robust structure. Dan volunteered to do this for FPR, so many thanks to him, and if you need a website, consider working with Pilcrow.

The fact that FPR had to depend upon Dan’s generosity for this redeveloped website is indicative of our status as an amateur organization. All of those involved in this strange project are involved for love, not money. This is, as you might expect, both good and bad.

On the good side, I’d point to the case that Wendell Berry makes in his essay “In Distrust of Movements.” He enumerates the ways that movements tend to go astray and fail to address the root causes of the problems that call them into being. As an alternative, Berry proposes launching a bold new initiative called the “Movement to Teach the Economy What It Is Doing.” Berry says that he will participate in the MTEWIID on three conditions: 1) that “this movement should begin by giving up all hope and belief in piecemeal, one-shot solutions,” 2) “that the people in this movement (the MTEWIID) should take full responsibility for themselves as members of the economy,” and 3) “that this movement should content itself to be poor.” FPR does pretty well when measured by these standards; we certainly excel at the last one. (Although if you want to read about one organization that is putting us to shame, see Matt Miller’s groundbreaking “Robert Farrar Capon Memorial Center for Needless Splendor and Research Institute in Unnecessary Studies.”)

Berry goes on to elaborate on the benefits of poverty and the dangers of being well-funded:

Too much money … attracts administrators and experts as sugar attracts ants—look at what is happening in our universities. We should not envy rich movements that are organized and led by an alternative bureaucracy living on the problems it is supposed to solve. We want a movement that is a movement because it is advanced by all its members in their daily lives.

Any localist movement worth its salt needs to shun professionalization and succeed or fail in the work done by people in their own places. But there is a difference between “too much money” and “enough” money, and this brings me to the drawbacks of our amateur mode of operation.

The risk is always that FPR continues and grows by exploiting the loves of its amateur contributors.

The risk is always that FPR continues and grows by exploiting the loves of its amateur contributors. There are the many talented authors who write for us, and whom we do not pay. (Take a moment to look through our wise, hard-working writers and reflect upon the fact that while many of them regularly write for paying publications, they also donate their writing to the Porch.) John Murdock records fascinating and thoughtful podcast episodes. Matt Stewart and Adam Smith edit essays for the website, and our editorial interns do the work necessary to keep new essays appearing here each week (and our new intern, Nina Tarpley, also drew the sketches for each of the new section pages). John Bilbro does the technical work to keep the website up and running (which has involved a lot of labor over the past few weeks).

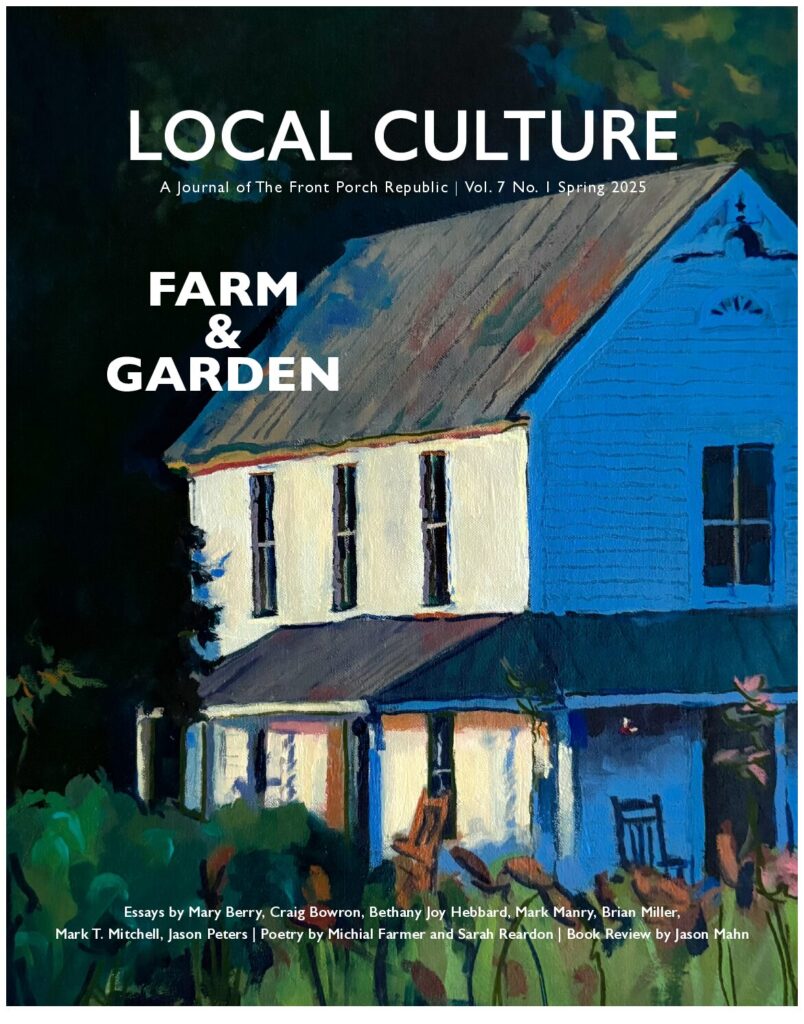

Jason Peters in particular has labored in thankless obscurity since trading in his bar stool for an editor’s pen. He puts together two beautiful and incisive issues of Local Culture every year—and he does so with no budget to pay authors. He’s also been editing the books in the FPR book series, but he is in the process of trying to pass that work on to others. We’d very much like to pay at least a token to the editor(s) who take over the book imprint.

Thanks to generous donors over the years—people who have been willing to give money to an “organization” with no five-year plan, no employees, no strategy for effecting global change—we’ve been able to expand our work beyond this website. In 2019, a significant donation enabled us to launch our print journal, and each issue now gets mailed to almost 1,000 subscribers. Other donors have enabled us to host some quite lively conferences (including our upcoming fall gathering at Baylor with Matthew Crawford). But we haven’t wanted to hire a development officer or become dependent on foundations or put up a paywall or take one of the other usual paths to bring in a more steady and predictable revenue stream.

I don’t pretend, though, that staying poor doesn’t entail plenty of drawbacks. Even Thoreau, after waxing eloquent about how virtuous poverty and simplicity are, includes a poem by Thomas Carew titled “The Pretensions of Poverty” that opens with a blistering critique of those who think poverty magically makes one pure and noble:

Thou dost presume too much, poor needy wretch, To claim a station in the firmament Because thy humble cottage, or thy tub, Nurses some lazy or pedantic virtue In the cheap sunshine or by shady springs, With roots and pot-herbs; where thy right hand, Tearing those humane passions from the mind, Upon whose stocks fair blooming virtues flourish, Degradeth nature, and benumbeth sense, And, Gorgon-like, turns active men to stone.

FPR’s “necessitated temperance,” in Carew’s phrase, isn’t really a virtue, and there are many goods that poverty precludes us from pursuing. Yet despite our unprofessional and unoptimized and unstrategic mode of business, FPR has managed to celebrate its sixteenth birthday. (I guess we can get a driver’s license now?) The analytics software tells me that readership is up. We receive more thoughtful submissions than we can publish, even though we’ve been increasing the number of essays we run each week. There seems to be a real hunger these days for grounded discourse, for humility, for a focus on perennial questions rather than the outrage de jour. It’s very encouraging to hear from grateful FPR readers via email or, even more so, in person when I’m at our annual conferences or speaking elsewhere. The Porch continues to play a valued role in inspiring and encouraging and equipping people to navigate our strange, techno-addled world and to inhabit their places with grace and courage and love.

I don’t know what the future holds. Amateur operations are fragile and tenuous. But we’re grateful for a much-improved virtual home from which we will continue the paradoxical project of encouraging one another on toward love and good deeds in the myriad local places where we make our earthly homes. May the Front Porch Republic continue to be a movement that is a movement because it is advanced by all its members in their daily lives.

Image Credit: Dennis Miller Bunker, “Roadside Cottage” (1889) via National Gallery of Art

1 comment

Brian Miller

Although I am not one typically to celebrate change, this is good. The new website looks impressive. And, a big thanks to all of you who have and continue to keep this project alive.

Comments are closed.