Tech skeptics like to use Romantic imagery. Thoreau at Walden. The Inklings in a smoke-filled room of The Eagle and Child pub. Nineteenth century pastoral paintings. When they are trying to explain the humane conditions they dream of, they inevitably look backwards. They often get mocked for fetishizing the Amish, chided for their holier-than-thou pronouncements, or merely dismissed for their hysteria. Because, of course, we don’t live in 1845 when Thoreau went out to Walden or 1935 when the Inklings were meeting. We live in 2025.

And while you can still go for a hike or dress up in tweed jackets and smoke pipes, I find my skepticism towards tech makes me often feel less like an Inkling and more like Chuck Magill from Better Call Saul. Chuck is a lawyer who is convinced he has an allergy to electromagnetism. As a result, he becomes a recluse, and every visitor to his house must leave all electronics — cell phones, watches, pagers — in his mailbox before coming in. Almost no one believes the allergy is real, but people humor him.

While you can still go for a hike or dress up in tweed jackets and smoke pipes, I find my skepticism towards tech makes me often feel less like an Inkling and more like Chuck Magill from Better Call Saul.

Chuck is in the strange position of being highly articulate about his malady while knowing that everyone thinks he’s crazy. The unspoken judgement weighs on him.

While I believe critics of social media, smartphones, or AI are actually correct in their assessment of reality, unlike Chuck, I think it is also true that the world often perceives us as some version of Chuck Magill. After all, just look at the tech skeptic’s prescriptions: Leave your phone in a box far away from the family, unplug your TV and hide it away, read real books and enjoy uninterrupted conversations. Though he comes at it differently, the outcomes are about the same.

He doesn’t own a smartphone, he doesn’t own a TV, and he doesn’t use a computer — he’s practically the Wendell Berry of Albuquerque!

If you are a tech skeptic, you must face the discomfort and self-doubt of breaking from the herd. There’s an instinctual fear of going against the grain, and then there’s also the very reasonable fear that you’ll be lumped in with the loonies. Paul Kingsnorth has written about how Ted Kaczynski — aka the Unabomber — was wrong to mail bombs but essentially correct in his condemnation of our technological society. For most of us, “The Unabomber had some good points” is a position we’d rather not defend.

Nevertheless, you may identify with how the author Steven Pressfield described the residents of a halfway house he once stayed in:

What I concluded from hanging out with them and from others in a similar situation was that they weren’t crazy at all, that they were actually the smart people who had seen through the bulls— and because of that, they couldn’t function in the world. They couldn’t hold a job because they just couldn’t take the bulls—, and that was how they wound up in institutions, because the greater society thought, “Well these people are absolute rejects. They can’t fit in.” But in fact to my mind, they were actually the people that really saw through everything.

So just to recap, on one side, you have all the normal people, and on the other, Paul Kingsnorth, the Unabomber, and halfway house residents. Which team would you rather join?

Then again, now that “normal” appears to be one-year-olds on iPads, universal cheating on college campuses, and AI as therapist, guru, lover, friend, and potentially executioner if things go sideways…

Well, I do feel like I’m taking crazy pills.

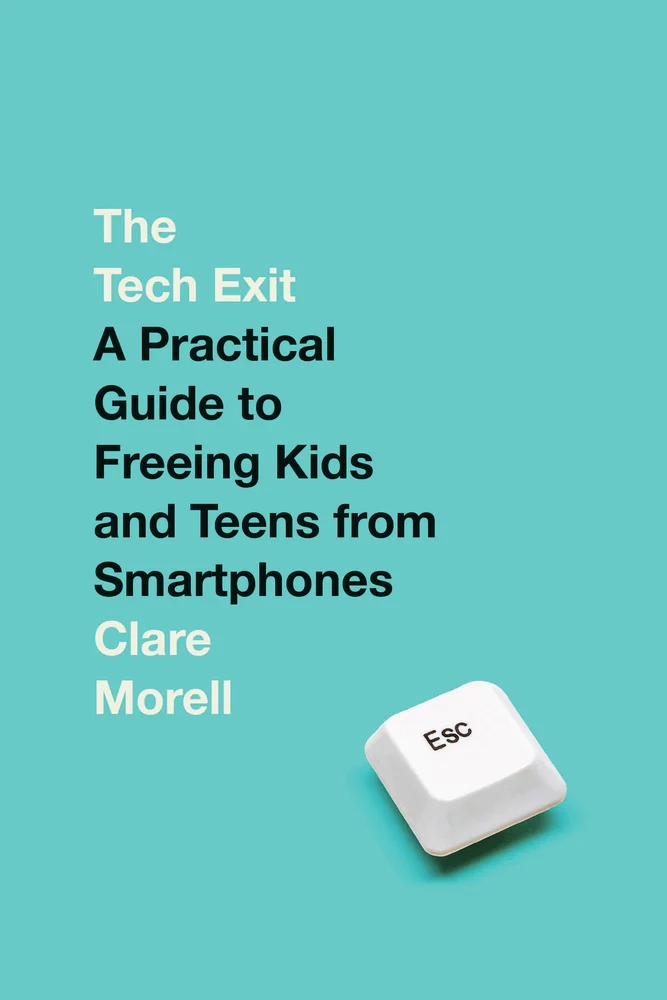

I recently hosted Clare Morell and 25 guests to discuss her new book The Tech Exit: A Practical Guide to Freeing Kids and Teens from Smartphones. The subtitle says it all: Morell thinks kids should not have smartphones, social media, tablets, or video games ideally until they’re 18. While I think this is true (though hardly easy to execute), I have never been in a room where everyone else agreed with this premise.

Time after time, Clare would say something that I believe but am usually embarrassed to say: “Parental controls don’t work. Total abstinence is the best approach for kids. Some kids find texting to be too compelling, even on a dumb phone,” and I’d see heads nodding all around the room. Not only that, parents would chime in to amplify her point:

“We found out how to lock down a Google Pixel so you can’t access the internet — and whenever an update breaks our parental controls, we pay whichever kid tells us first.”

“Imagine if you had to make sure the liquor store was carding your child. We count on them to verify the age of their customers. We don’t say, ‘Oh, he went to the liquor store again. We’ve gotta be more on top of that.’ No, that’d be crazy. But that’s exactly what these social media companies expect us to do. They expect us to constantly monitor what our kids are seeing and doing online!”

It was the first time I was talking to people who had read the same things I had and come to the same conclusions. I’m so accustomed to caveating and apologizing for sounding “crazy,” that it was refreshing to have an honest, direct conversation about the challenges we face as parents instead of dancing around the topic for fear of offending or coming off as a lunatic.

With the pace of technological change, there are two broad visions for childhood that are emerging. On the one hand, tech boosters offer AI as a panacea. AI would be the ultimate confidante, coach, and tutor — it never gets tired, it never forgets, it is always tailored just to you. With such a tool, you would become superhuman.

On the other hand, skeptics are calling for a total opt-out for their kids. Morell advocates for fasting from the digital and feasting on the real — that means in-person relationships, time outside, unstructured play. Reading physical books, learning calligraphy, going fishing. In other words, rather than trying to become a cyborg that supersedes homo sapiens, Morell aims for a human being fully alive.

While the title of The Tech Exit emphasizes what we leave behind, the book is principally concerned with what we’re striving for. In that sense, Morell and her fellow tech skeptics are nothing like Chuck. He dreams of overcoming his allergy so he can reenter normal society. We reject the status quo because we want something better for our kids. Chuck is fixated on this illness he hates. Clare’s advice is to focus on what you love and want your kids to love.

That may mean we admire Henry David Thoreau, the Inklings, or Wendell Berry and do our best to approximate that in our modern lives. To my mind, that’s no sillier than admiring St. Augustine even though we don’t live in 4th century North Africa. I think the bigger threat is not that we would be posers but that we would succumb to despair.

I hope Clare’s book catches on and opens the door for more parents to band together. I want you all to experience how it feels to have another parent tell you, “You’re not crazy.” Because despite what the rest of the world says, I really think we aren’t. Then again, that’s exactly what a crazy person would say.

Image via Freerange