With each passing year I fear that any possibility of a national reckoning on the Covid fiasco is slipping away in the sands of time. Even though all things Covid seemed to have split the entire country right down the aisle, in this last presidential election our recent yearslong bout with scientific totalitarianism was at best an afterthought.

As the issue recedes into the recesses of history, and as young people grow up who will have no memory or comprehension of those bizarre years, I start to lose hope that we will learn anything from the experience. As time passes, it seems a consensus is gradually forming that we couldn’t have done otherwise, that everything that was done had to be done, and that it was all for the best.

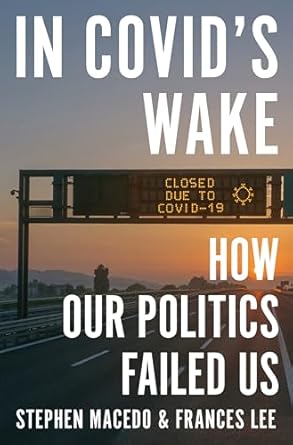

On the other hand, the more time passes, the safer people will feel to make an honest assessment of what they lived through, even if it seems to violate this unspoken consensus. This is what Stephen Macedo and Frances Lee have courageously done with their latest book, In Covid’s Wake: How Our Politics Failed Us (Princeton University Press, 2025), and I applaud them for it.

Yes, many books have been written in the last few years that rail against lockdowns, mandates, school closures, PCR tests, masks, social distancing, and everything else. But this book hits much harder, as it comes from two high-status Princeton political scientists whose politics are well within the liberal mainstream of academia, and who have each taken leadership roles in their discipline. But here they are, directly critiquing what they themselves call “orthodoxy in professional progressive circles” (p. 8).

From my perspective as a longtime skeptic of the official Covid narrative, the book is on the one hand a watershed moment: perhaps Macedo and Lee have pried the door open for more professional establishment types to follow them through—perhaps a flood is even imminent. We all learned how herd behavior works, didn’t we? Even failing that, the mere fact that they have reckoned honestly with the policies and politics of the Covid years is a quantum leap forward, while most liberals either forget it or pretend it was all justified.

On the other hand, having read the book thoroughly, I also can’t help but notice a number of blindspots and unwarranted assumptions the authors seem to retain about Covid, and more broadly, about politics and even human nature. They have come most of the way, but I stand here beckoning them to take the last few liberatory steps.

Let’s start with the title. In Covid’s Wake implies that “Covid” was a wave, a natural phenomenon that washed over us whether we liked it or not. This imagery is at odds with the central claim of the book, that most of what went wrong during those years was due to our policy response to the disease. Early on in the book, the authors call out those who dodge accountability for bad policies in precisely this way, but the title seems to imply it was all—say it with me—“because of Covid.”

The subtitle is How Our Politics Failed Us. I wondered as I started the book to whom the “our” referred. I thought that it might refer to the liberal intelligentsia who haunt the halls of Princeton and other Ivy League schools, or perhaps modern liberals more generally, whose overweening concern for victims and safety culture provided the ideological drive for so many of the draconian policy responses to Covid.

But as I finished the book, it became clear that the “our” referred to us as a country, and was more or less laying the problems of Covid at the feet of that universal bugbear, political polarization. After all that the authors had asserted in the book about the dangers of the rule of experts, this framing seemed not only quotidian, but a walking back of many of their key insights.

Getting it right

The book has an excellent chapter that lays out the pandemic planning that was in place before 2020. The bottom line here is that most non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs: think lockdowns, school closures, masks, distancing) would not be worth the costs they would impose on society. Most official pandemic plans questioned whether such measures would work at all, and ruled them out, while a few plans kept them open as options. There was some debate, but the weight of the recommendations was against them.

Macedo and Lee’s decision to start here is wise and very effective. It demonstrates their thesis that our capacity for deliberative debate and collective decisionmaking was commandeered by panic, swept away in a flood tide of “consensus.” Our experts had thought about these things in planning for the future, and rejected them. Few bothered to look backward at the expert consensus before Covid. I remember when I finally looked up pandemic plans from the before-times in the fall of 2020, because doing so changed my whole outlook on all the ways we had already been locked down at that point. These policies weren’t just unprecedented; they actively violated the vast majority of expert recommendations in pandemic policy.

The next part of Macedo and Lee’s story tells of China’s severe lockdowns and how they were extolled among academics, journalists, and government officials. Looking back, they find this response, and the resulting emulation of lockdowns virtually worldwide, perplexing. “It seems incredible—even having lived through it—that such a pervasive, global suspension of basic liberties was undertaken with widespread public support” (p. 67). I second the emotion. A number of explanations are offered: the credulity of government officials toward mathematical models, and a desire to oppose Trump, who did all he could to pin the virus on China. And most shockingly, the fact that Deborah Birx, the White House coronavirus response coordinator, admitted later that “Fifteen Days to Slow the Spread” (remember that?) “was just a way to eventually sell Trump on longer shutdowns” (p. 68). And once those fifteen days had begun, we had already passed the point of no return, as any leader who tried to reopen things would be cast as irresponsible or even malicious. Killing grandma, as we all know by now.

I had forgotten how much debate there was in March 2020 while the situation hadn’t yet been, well, locked down. And the debate was not a partisan one—it was more like lunch on the first day of school, when people hadn’t figured out which friend group to sit with. Many top experts and authorities had been playing the role of the voice of reason by calling for carrying on as normal. Even MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow, on March 3, said on The Tonight Show that, yes, maybe two percent of people might die from it (almost a hundred times the eventual known infection fatality rate), but “we don’t have to do anything outrageous…we don’t need to change our lives drastically at an individual level” (p. 70). And by the time 35 states had already closed schools, on March 15, the CDC itself actually advised that school closures would be ineffective. But the wave was already generated, and not even the top national authority on such matters could stand against it at that point.

But in a few locales, cooler heads did prevail. The book takes a nice look at Sweden, for so long a favorite whipping boy of zero-covid interventionists. Macedo and Lee conclude by saying that Sweden got it right when they decided not to shut down society and instead protect the vulnerable and let herd immunity develop naturally (Japan’s example is similar). The book is on firm ground here, noting that Sweden has had the lowest overall excess mortality in Europe throughout the Covid years.

Herd immunity itself gets a fuller treatment in the next chapter, along with natural immunity, as another example of “the science” changing overnight. The world seemed to forget about natural immunity altogether, so that somehow only vaccines could provide immunity. Nevermind that vaccines were developed as an artificial imitation of natural immunity. Instead, an established central concept from immunology got banished to the mysterious world of “fringe epidemiology.”

Another sharp arrow in the book’s quiver is its documentation of how Dr. Fauci and other leading scientific authorities conspired in secret to coordinate “a quick and devastating takedown” of the Great Barrington Declaration, which essentially proposed in mid-2020 that we do as the Swedes were doing. The three eminent epidemiologists who made the proposal were deemed “fringe” and the campaign to discredit them in the media successfully stopped any effort at policy change.

In a separate chapter, we are shown how Fauci and other leading academics also conspired via email to put a lid on the lab leak theory early on. The theory was claimed to be false, but more importantly, out of bounds. The authors demonstrate clearly that the gain-of-function laboratory origin is overwhelmingly likely to be true, and also that top American scientists colluded with Dr. Fauci via email to cover it up, pretending that the virus resembled something that would emerge in the wild when their own previous emails show that they confidently thought the exact opposite before Fauci flexed his considerable funding leverage.

The official denials of natural immunity and laboratory origin of the virus were outright scandals, and it is a shame that they never came to prominence in the national news cycle. While this book is to be commended for telling it like it is for each of these stories, it also pulls some important punches.

For one, the authors automatically concede that “honorable motives lie behind research to make pathogens more dangerous to humans” (p. 208). The idea that an entire research program could be based on less honorable motives seems out of bounds for them, despite the fact that such viruses would be most valuable to governments as biological weapons. Moreover, the stated justification for gain-of-function research is to be able to produce vaccines for superviruses our enemies might engineer. But this is patently ridiculous. For starters, it is astronomically improbable that our scientists would produce the exact same superbug that enemy scientists produced. This supposed just-in-case defense strategy against bioweapons is nowhere near feasible, and any reasonable observer must conclude it is a pretext for bioweapons development. But the authors stop short of doing so.

To their great credit, Macedo and Lee repeatedly point to the fact that the experts have incentives and motives of their own that are not in the public interest. But they seem to resist taking this observation to its logical conclusions in this case and calling this out as part of a military-industrial complex. But nowhere in the book is this concept introduced, or any other critique that would indict entire systems in our vast bureaucracy.

Safe and Effective? Interventions Both Pharmaceutical and Non-

The fifth chapter is the densest in terms of data, and this is where Macedo and Lee bring the receipts when it comes to the ineffectiveness of lockdowns and the like. They first demonstrate how polarized US state responses were, with red states with relatively few restrictions and blue states far more gung-ho on stay-at-home orders, school closures, and mask and vaccine mandates. Unsurprising, yes, but interesting to see such data in visual form.

Even more interesting were all the scatterplots that show a null relationship between various interventions and Covid mortality. The speed and length of governors’ stay-at-home orders, the length of school closures, and a general index of stringency of Covid policies—none of these made any statistically detectable dent in the number of Covid deaths, even in a simple bivariate chart with no controls (although it must be noted that how these deaths were counted was contentious and misleading in many states). The authors develop a multivariate statistical model, and none of these NPIs makes a difference there either. The results are absolutely clear that such policies were plainly ineffective. This is a major contribution, not just to our understanding of pandemic policies, but hopefully to prevent such policies from ever being trotted out again in the future.

The major exception for Macedo and Lee is that decidedly pharmaceutical intervention—the jab. They begin with a bivariate scatterplot of the US states charting covid mortality with the percent of the population fully vaccinated. In contrast to the null results for the non-pharmaceutical interventions, there is a clear trend here: states with higher vaccination rates had lower Covid mortality (R2=0.476, a substantial correlation). Although they later run a multivariate model to control for confounding factors, the authors do not point out the possibility that other factors may be driving the correlation at this point.

The multivariate model of the US states predicting their Covid mortality includes vaccination rates, stringency of NPIs (again, completely ineffective), and some control variables: percent over 65, percent urban, percent obese, percent nonwhite, and a dummy variable for the handful of states hardest hit by the first wave of Covid. Percent fully vaccinated, along with most of the control variables, is statistically significant, while the index of NPI stringency is not. So, the efficacy of the vaccine remains when controlling for other factors, and from this the authors conclude that the Covid shots were effective and stop their analysis there.

I can understand the authors’ reluctance to discuss the vaccines in depth (they don’t), given that this is still a live issue, more so than other Covid policies. But precisely because of this, a little more rigor here is called for, especially given that a fair amount of recent research concludes that the vaccines had no such effect (and especially now that the government has pulled funding for any further mRNA vaccine research based on safety concerns). One can think of other variables that are omitted from Macedo and Lee’s model. Additional control variables might include chronic disease levels, or the average temperature as a measure of a state’s climate. The healthy vaccinee effect may also be confounding their results, but there would be no way of testing or controlling for it (one would need a randomized controlled trial).

You might remember that much of the counting of Covid deaths was done under the heading of “died with Covid” rather than “died from Covid.” Given these controversies, it is surprising that the book only investigates this dependent variable. Macedo and Lee could easily have run the same models to predict all-cause excess mortality. This would provide a strong robustness check on their results, and would probably even demonstrate not just that lockdowns and school closures didn’t help, but that they did real harms measurable in human lives taken by missed cancer screenings, deaths of despair, and other causes of death that dwarf covid. But the authors didn’t do this, either because they did not know about the problems with state counts of Covid deaths, or perhaps because it would lead to questions about vaccine safety they didn’t want to have to ask.

In any case, the beneficial effect of the vaccines remains statistically significant in their model. They claim that “vaccination rates strongly predict variation in states’ Covid mortality” (p. 153, emphasis mine). Ok, but how strongly, exactly? Unfortunately, no measure of the substantive effect of vaccination rates is offered, even though this is now conventional in political science research and easy to do. The best way I can estimate this as a reader is by comparing the R2 (the measure of how much variation the model explains) of the full model to that of the controls-only model. The control variable model comes in at .52, explaining 52% of the variance in Covid mortality. Adding in the NPIs and vaccine uptake, the R2 ticks up to .58. At most, vaccination rates explained 6% of the variance in covid mortality between states, and that is assuming that no other omitted confounding variables are playing a hidden role here. This is hardly what I would call a strong effect. Most of the predictive work of the model is being done by the control variables, especially age and obesity.

This is not just quantitative nitpicking, but points to a larger issue with the book. For all the Covid controversies that Macedo and Lee have changed their mind on, from the lab leak “conspiracy theory,” to lockdowns, they still have a blind spot for the vaccines. I was expecting there to be a chapter, or at least a section, detailing the controversies, coverups, and conflicts of interest surrounding the vaccines. The shots and the mandates were perhaps the biggest of all the Covid hullabaloos, but these authors seem to avoid the topic as much as possible, really only addressing the jab in their statistical model and, thankfully, in arguing that natural immunity is at least as good as vaccine immunity. Perhaps they just wanted to avoid excess controversy. Or maybe they didn’t want to risk being seen by their colleagues as too far in the Covid deep end. Perhaps the two authors had disagreements about the Covid vaccines. But its absence in most of the book is palpable.

When the book mentions the vaccine, it is often in the context of broader pandemic planning, specifically the strategy of dealing with the pandemic “until there’s a vaccine.” The authors do praise the Great Barrington Declaration and they do think natural herd immunity was a viable strategy for coping with Covid. But they never go so far as to question the “until there’s a vaccine” strategy itself. This is one of the major headscratchers for me as I ponder the Covid years. We had never made a vaccine of any type that could confer any lasting immunity to a coronavirus. This is why there’s never been a vaccine for the common cold, for instance. So why on earth would we all assume that a vaccine would save us from a coronavirus pandemic? Unfortunately, Macedo and Lee don’t ask this question. Nor do they examine the coordinated suppression of various effective treatments for covid-19, treatments which, if their efficacy had been officially recognized, could have nullified the rationale for an Emergency Use Authorization for the novel vaccines.

I would guess the authors are sympathetic to people who remained unjabbed despite mandates (having read the book, I still don’t have enough to go on to be sure of this). But they have no such sympathy when it comes to those who question other vaccines. There are scattered references throughout the book to generalized vaccine skepticism, which is typically grouped with “other dangerous untruths” (p. 272). In another passage: “combating errors such as election denialism and climate and vaccine skepticism is important—as we certainly affirm” (p. 18).

But this kind of stance, during the Covid years, is excoriated by the authors themselves throughout the book with regard to all other things covid. Labeling criticism of vaccines as out-of-bounds was exactly the strategy used to justify vaccine mandates during Covid, and to justify censorship of criticism of said mandates. While the authors offer powerful criticisms of censorship, they never do offer a critique of the mandates. Shockingly, they hardly bring them up. This is a major disappointment, as this was one of the greatest rights violations that the Covid era wrought. And the suspicions about the covid vaccines have now expanded, unsurprisingly, to the proliferation of vaccines more generally. Sadly, despite their overt recognition of the need for open debate in science and in politics, Macedo and Lee still seem ready to ostracize anyone expressing skepticism about vaccines, climate change, or election results as anti-science and worthy of “combating” rather than debating.

The sixth chapter makes one of the most important points one can make about the Covid years, although it is a relatively safe one to make. The point is that Covid turned to madness because of tunnel vision, that so much went wrong because we all became focused on one thing: preventing Covid. Yes, we debated about test results, infections, cases, hospitalizations, and deaths: which one should we focus on? But we forgot to look at everything else. This is what gave rise to lasting lockdowns, school closures, and the general long-term upending of normal human life.

This chapter documents the many costs of such draconian measures. The costs came (and are still coming) in many forms: manifold economic costs, educational costs, health costs, both physical and mental, and the costs of social dislocation. This chapter is vital, as the costs are devastating to read about. And Macedo and Lee are absolutely right in locating the source of the problem in an exaltation of science and scientific expertise above other equally vital forms of expertise, such as social sciences and humanities. It’s not just that we outsourced policy decisions to experts, but to a decidedly narrow coven of experts at that.

Putting the panic in pandemic

But one thing the authors seem to miss is that the very concept of a pandemic was a huge part of the problem. Although sometimes they will refer to the Covid years as a “crisis,” or my personal favorite, “fiasco,” they usually refer to the Covid years as “the pandemic.” Of course, officially there was a global coronavirus pandemic, as declared by the World Health Organization. But you can’t spell pandemic without panic, and that is exactly how the word functions psychologically.

We have all been conditioned—by movies like Contagion, novels like Outbreak, and board games like Pandemic—to equate a pandemic with the most serious and urgent possible crisis. But did you know that the WHO also declared a global pandemic of swine flu in 2009? And a month before doing so, they actually greatly loosened the standards for infection and mortality levels when they changed their criteria for declaring a pandemic. Also, there is still a cholera pandemic going on for the past sixty-four years. Yes, you’ve lived through not one, not two, but three global pandemics (at least). Tell your grandkids someday!

The point is that there is a huge disconnect between what “pandemic” now officially means among experts, and what it means in the minds of regular people all over the world. Like cholera, the Covid pandemic has not been declared over by the WHO. In 2023 it was only declared “no longer a public health emergency of international concern.” But that is exactly what most people hear when they hear “pandemic.” It means emergency, in red letters and all caps.

And any emergency is a demand for all hands on deck. While the authors argue that we needed more hands on deck to address the pandemic, it seems to me that the real issue wasn’t that social scientists weren’t consulted, but that it was all hands on this particular deck—exactly the tunnel vision Macedo and Lee decry, and exactly what a state of emergency calls for. Also, few people are familiar with the term endemic, the phase that follows the pandemic stage, where the disease becomes a regular and predictable part of life, which it now obviously has. I remember my first doubts about covid came when I noticed the number of cases did not simply continue to exponentially expand (part of the definition of a pandemic), but contracted and expanded again in waves. I started thinking, does that mean it’s endemic or will be soon? I remember conversations with otherwise intelligent colleagues who had never heard of the term endemic and who thought the pandemic would end only when we “beat” the virus. The idea of zero-Covid was a pernicious lie from the start, and Macedo and Lee are right to castigate its advocates. But their habitual use of the word pandemic is part of the problem. Even though it is common coin among the literati, it functions as a scare-word for almost everyone (or at least it did in the before-times). And this was a major part of why policymakers lost their sense of proportion.

Polarization and Pondering

Another thing that fed the irrational fear of Covid was the masks, and the book devotes one of its strongest chapters to them. The authors once again demonstrate thoroughly that the actual consensus among the scientific literature was that masks don’t stop respiratory viruses, and that the two studies that show otherwise were in fact very weak evidence. They go on to point out the various costs of masking, especially to children’s development and schooling. They conclude with important observations of the conflicts of interest that experts have, and how expert advice needs to be both checked and balanced.

Another fine chapter, but they stop short here as well. To my mind, the most important effects of the masks were psychological: to keep us afraid, to cover up smiles, to view each other as a threat, to remind us of the state of emergency we were living through, to keep a particularly divisive issue at the front of mind, and for those that knew better, to accustom them to complying with something they knew to be nonsense. While such effects are perhaps less scientifically studied than the ones discussed by Macedo and Lee, I do wish they discussed them at greater length.

Here and elsewhere, Macedo and Lee consistently lament partisan polarization and how it seemed to go into overdrive during Covid. There is a kind of “why can’t we all just get along” vibe that seems to come along with such complaints. One key reason Covid made polarization worse was that it literally put polarization in your face so that there was no escaping it, no denying it, and no ignoring it. Masks were the most frequent and unavoidable reminder of our political divisions, and oftentimes we wore them only to avoid conflict. The same could be said for many who got the shots. In normal times, you can usually avoid talking about politics when you anticipate disagreement, and you can instead turn the conversation to other topics or avoid discussion altogether. It’s a marker of polite company, and a virtue, to be able to do so. But under Covid we were not able to do so because we would wear it on our very faces. This connection between masks and polarization seems obvious to me, but it is never brought up in the book.

For Macedo and Lee, polarization was a big part of what failed us about our politics. And having lived through the Covid years, of course I sympathize. But while we all can complain about polarization, the fantasized world in which we all get along looks different for each of us, and is of course colored by one’s own politics. Some would have appreciated a world in which we all agreed to the mass testing, lockdowns, masks, vaccines, etc., in a team-spirited effort to beat Covid. Others, like myself, would have preferred a world where we all saw the absurdity of each of these things and agreed on the sanctity of the right of each individual not to be forced into any of them. Those are both worlds free of polarization, where “we all just get along.”

But what was exceptional about Covid was not that we were divided, but just the opposite: far too many of us went along with the herd unthinkingly, and often even when we already knew better. Nearly everyone was on board in the beginning. It was exciting to be part of a real historical event, a society-wide war effort against a virus that threatened us all. Shutting down life and masking up felt at first like an exciting movie, and it felt effervescent, like being part of something big.

There were a few immediate dissenters (and good on them!), but most of us who came to view the crisis more skeptically, like Macedo and Lee, had done so only as a result of a process of observing and questioning. We had to learn these things, and verify them: that the virus was not nearly as lethal as we were originally led to believe, that lockdowns were not worthwhile and not recommended by public health experts, that the inventor of the PCR tests insisted they could not be used as diagnostic tools, that MRNA vaccines had never been tried on any human population before… I could go on, but the point is that I was not predisposed to these polarizing views, but instead I had learned that they were true, even if I wished that they weren’t. And as much as seeing these things set me against the consensus, I could not unsee them. This is what made Covid skepticism a one-way door. For almost everyone who changed their mind in some major way at some point about Covid, including Macedo and Lee, the change went the same direction.

The authors claim that no learning took place from the comparison of the different US states’ policies, that no one really learned anything from our fifty “laboratories of democracy” when looking at lockdowns and school closures. While it is true that throughout the Covid years red states did their thing and blue states did theirs, in a predictably polarized fashion, it is simply not true that nothing was learned. At some point even the bluest states reopened schools. Who did they learn this from if not the states who reopened earlier? True, they almost never admitted that they stayed closed too long, or that they never should have been closed at all, but they would not have reopened at all if they hadn’t learned from other states and countries that it was safe to do so. Similarly, although opinions about the vaccines are still a hot potato, nearly everyone at some point decided to not get the next recommended booster, except for a truly dedicated few.

This is how the pandemic was brought ultimately to an end, by leaders and regular people ultimately learning that the juice is no longer worth the squeeze. I agree with the authors that it took too long. And while I could lament how long Macedo and Lee took to come around on Covid, more than anything I am glad that they have come to the conclusions they have. Clearly they themselves learned from their own astute analyses of our laboratories of democracy, and hopefully many others will learn, and be led through the one-way door by their book. Minds can be changed, but it does take time.

If we lived in a world where “we all just got along,” such a thing might never happen. In a world of uniform consensus I would have had much less occasion to change my mind. For those who decry political polarization, Covid was a be-careful-what-you-wish-for kind of moment. It was not polarization that failed us, but the consensus itself. Polarization is what gradually brought us out of the trance. Thank God for political polarization, I often found myself thinking. Without it we might never have escaped from the consensus that was so quickly built up and so rigidly enforced. Without partisanship’s motivated reasoning, we might instead have gone along with all the lies for good. Macedo and Lee reference Green and Fazi’s book, The Covid Consensus, but they could learn more from its framing of the covid era: it was the consensus that was the problem. The only problem with polarization is when we are too stubborn to learn from it, but without some degree of polarization there is nothing to learn from, and certainly no laboratories of democracy.

Trust and Trustworthiness

The book has an excellent chapter that looks critically at misinformation and noble lies. And although the connection is not pursued explicitly, closely juxtaposing these two ideas is a stroke of genius as it immediately invites the reader to question what the difference is between misinformation and a noble lie. Spoiler alert: the difference is merely in who is telling the lie.

The authors make a strong case against the paternalistic logic of the noble lie, but the funny part is that they end up drawing conclusions that sound so obvious they shouldn’t even need to be said. That “people have a right to a frank assessment of the available evidence” (p. 273), rather than be told only half-truths that public health policymakers want to tell them in order to manipulate their behavior, seems self-evidently true to me, but perhaps I’m the choir being preached to here. Their takedown of a 2023 peer-reviewed article in a top medical journal is perhaps the most gratifying part of the whole book (see p. 276; unfortunately it’s also a perfect example of the authors’ blind spot for the vaccines). They highlight five claims the article assessed to be erroneous misinformation about covid, and all five are demonstrably true. It’s clear that the biggest purveyors of misinformation are the official authorities themselves.

They make a strong and effective case against censorship and other forms of official narrative control, and against the paternalism and moralistic groupthink that energized such overreaches of power. And this is one of the book’s strong points. But there is some hedging of bets here as well, and a framing of the issue that is still, ironically, a bit paternalistic. The authors frequently (but by no means exclusively) resort to the argument that it is wrong to mislead the public because it creates mistrust in the authorities. But even if misleading the public didn’t create mistrust it would still be wrong. In fact, by my lights, it would be even worse if you could maintain the public’s trust while continually deceiving them. Deceiving the public is wrong because it’s wrong, and not because it erodes the public’s trust in the authorities. The mistrust isn’t the problem. It is the solution: the only appropriate response to government lies. And as I.F. Stone famously said, all governments lie. Hasn’t Covid at least taught us this?

Furthermore, while Macedo and Lee rightly oppose the paternalism of the noble lie, this argument against the noble lie is based on the assumption that in the ideal political system the public would and should trust the government as a paternal figure that has its best interests at heart. In other words, they are saying the noble lie is bad because it makes paternal governance more difficult to achieve. A better framing would say that the authorities should be trustworthy, rather than saying that the public should trust the authorities. Of course, their framing of the issue this way could be chalked up to the intended audience for the book being less sympathetic to the public and more sympathetic to the elite class of experts. But I think it goes deeper, and points to a more general worldview that is wrapped up in myths of progress.

Progress and the Scientization of Politics

In their concluding chapter the authors make claims that rest on nothing but assumptions of progress. “In the twenty-first century, one would think we would have learned to hedge against groupthink” (p. 295). It is as though the mere passage of time should make us immune to the irrational social phenomena of our past. The authors follow this line of reasoning further, and make it quite explicit. It is worth quoting at length:

In the twenty-first century, would one have believed that stigmatizations of dissent—precisely as described by John Stuart Mill in 1859, before the U.S. Civil War—would still be a recurrent feature of our liberal democratic institutions? That government officials would engage in an active effort to censor their political opponents for expressing dissenting views? That scientists would distort their own accumulated knowledge, as they did with the definition of herd immunity, or seek to stifle debate on questions of legitimate concern, as they did with the coronavirus’s origins or the efficacy of population masking as a means of controlling the spread of disease? Perhaps these questions are naïve. Maybe, as the opponents of liberal democracy have long said, there is no arc of moral progress. (p. 297)

I share their outrage about all of these things. But I respectfully submit that, yes, these questions are naïve. Welcome to politics, which is full of problems that we will always struggle with, that we will never learn our way out of. This is the nature of politics—it’s where we put the problems that can’t be solved (thanks to Adam Smith for this way of putting it).

Moreover, it is not cynical to recognize this reality. One can even simultaneously support the ideals of liberal democracy without believing that every ugly part of the exercise of power can be fully and finally cleaned up.

Perhaps this faith in progress has to do with their picture of science. As the excerpt above shows, Macedo and Lee save their strongest ire for the scientists who betrayed the principle of open inquiry. While the authors make a strong case that democracy should not be ruled by experts, they do seem to imply that science should rule over politics. Two consecutive chapter titles are “Science Bends to Politics” and “Politicized Science,” both of which implicitly urge that politics be kept out of science.

I share the sentiment. But the framing is interesting, and to say that all would have gone well during covid if politics had just stayed out of science would be wrongheaded. There is not much daylight between asking for politics to keep out of science and asking that disagreement be banned from scientific discourse. Many who refused to get vaccinated were told they were letting their politics impact a medical decision. To take a more extreme example, if Dr. Mengele’s abhorrent human experiments had been defunded by the Nazi government on the grounds that it contradicted the government’s political values, we can easily imagine him objecting that politicians should stay out of the science. But both these examples show that politics and its value judgments always stand above the questions of science. They in fact aim science toward the objectives we find valuable. Sometimes, as in the case of Dr. Mengele, we judge these objectives to be morally abominable, but this is not a judgment that science can make.

At a surface level basically everyone loves science and basically everyone hates politics, so it’s easy to get rhetorical mileage out of the politics-corrupts-science trope. But a reversed framing of the story provides a better diagnosis of what happened during covid: it was our politics that became corrupted by the science. Disagreement and dissent were constantly shut down in the name of science, as the authors carefully demonstrate throughout the book. Moreover, people seemed to want to dodge debates about values and turn them into debates about science. Instead of discussing the ethics of vaccine mandates, most people discussed the safety and efficacy of the vaccines, as though there could be nothing wrong with mandating a safe and effective medical treatment. Even if lockdowns had been shown to be effective in slowing the spread of covid, that alone would not in itself justify imposing them. Similar examples abound in debates about masks, school closures, censorship, you name it.

We retreated from the political—where we wear our values on our sleeve and advocate for them—to the scientific—where we pretend that all we disagree about is the data and how to best interpret it. Often it seemed that if one was right on ‘the science,’ one had automatically won the debate over policy. I’m not saying those scientific questions weren’t important—but only that value questions are a separate sort of thing, and that science cannot answer those.

Politics has been corrupting science from the beginning. What was novel about this coronavirus business was the degree to which science started to corrupt our politics.

Democracy and Rights

Though the book has plenty of powerful critiques of the politics of the covid era, two were surprisingly absent. First, the authors didn’t really investigate the short-circuiting of democratic processes under covid. There was a radical expansion of executive authority across the country, from the President to state governors and city mayors. Stay-at-home orders, mask mandates, school closures, vaccine mandates, and all kinds of restrictions were done with executive authority and often no input from our democratically representative legislatures. In most cases, declared states of emergency bypassed elected legislatures, and these often lasted well beyond any reasonable sense of emergency. It would be one thing if lockdowns had been deliberated on and voted on in the chambers of state capitols across the country, but instead, these draconian policies were put in place by naked executive authority without any such democratic niceties. The book remains silent on this particular democratic deficit under covid, and this is an area that still needs investigation.

Second, one of the most startling political revelations that I took from the covid crisis was how shaky the foundation of our rights and liberties was. More specifically, how few people actually believed in them. The idea of individual rights is perhaps the most central pillar of American political culture. I recognize that respect for individual rights had already been slowly eroding in various ways over the long term, but covid pulled the rug out from underneath my entire conception of our shared political values. Rights are not things that the government can decide you don’t get to have for a few years (or even for fifteen days for that matter). But this is exactly what happened when a moderately threatening respiratory virus came to our shores. Several legal and constitutional rights, many directly enshrined in the Bill of Rights, were weakened, threatened, or even negated under covid: freedom of movement, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, the right against unreasonable search and seizure, free and informed consent, and of course, bodily autonomy. People who had been chanting “my body, my choice,” for instance, dropped that sentiment altogether just to call for vaccine mandates. It was as though a spell had been cast over half of the population, and all the things they had claimed to believe, they simply no longer believed.

If we have rights, they don’t simply go away during an emergency. And this is especially true when the case for emergency is as weak as it ended up being under covid. If rights can be evaporated that easily, they are not rights at all, but government-granted privileges. Alas, neither does the book take this step in its analysis of the politics of covid.

I have harped on the book for all the ways it disappointed me, but I am a tough customer to satisfy, because at the political level, I felt covid like one would feel an earthquake. It shook my own political views significantly, reshaped my understanding of American political culture, and altered my understanding of both politics and science. However, we all have different experiences and draw different lessons.

Stephen Macedo and Frances Lee have drawn many fundamentally important lessons from the covid years, and they are writing to an audience of academics that desperately needs to learn those very lessons. Their exhaustive research on the pandemic plans that were overturned in a panic, their documentation of how the world came to emulate China’s excessive authoritarian approach, their incisive analysis of the costs and ineffectiveness of lockdowns, school closures, masks, and other covid policies, their frank exposure of the lies and coverups of the top medical and scientific officials, and their measured critique of the hypocrisy of official campaigns to combat misinformation that merely spout still greater amounts of lies—all of this makes for necessary reading.

For a covid news junkie like me, a lot of this comes as old news, but I still found much to learn from in the book, especially due to Macedo and Lee’s systematic approach to each topic they take on. I have been hoping for a reckoning about covid for years now, and this book is a major step in that direction. Here’s hoping more follow in its wake.

Image via Freerange.

4 comments

Sharon Newman

Dr. Darr, since you “have been hoping for a reckoning about covid for years now,” I recommend the following– A reckoning specific to the Church after covid is the recently-published “A House Divided: Technology, Worship, and Healing the Church After Covid” by Benjamin D. Giffone. ISBN 978-1-7336584-7-8.

Ben Darr

Thanks. You know, maybe I was too harsh on the title. After all, the title is an invitation to open the book, so maybe it doesn’t need to be any more strongly worded than it is. And at least the word pandemic isn’t in the title. Actually I think the authors do a fantastic job focusing on specific policy failures. I only wish they recognized a few more of them, and drew some stronger conclusions from them all.

Anselm Vrbka

Good piece — clear and thoughtful. Interesting point about the title seeming to shift blame back to the virus rather than policy. Do you think the authors should have chosen a more precise subtitle or framing to avoid that ambiguity, and would a stronger focus on specific policy failures make their critique more persuasive?

Ben Darr

And to be completely fair, the cover image is excellent, as the highway sign saying “closed due to COVID-19” at this point is obviously deceptive–it’s really closed due to panicked and irrational policy choices. If that’s not the message that comes through when you first start the book, it’s certainly the message once you’re into it.