Over the last 4 years, faculty rooms have been full of conversations about the dangers and possibilities of Artificial Intelligence. For all of the haters out there, there’s a growing number who think it’s the best thing since Google. As I’m writing this, I’ve just sat through another two-hour session discussing our implementation of and adaptation to AI. (Made with AI! Wow! Cool!) Some call it the “problem” of AI. But often, we don’t view it as a problem: It must be a gift to steward.

In my broadly evangelical institution, there tends to be an impetus to keep up with “the culture.” In some ways, it’s a dying need to be relevant. But outside of my institution, advocates say that we need to be prepared for the “AI takeover,” (so the conversation goes). There were some who opposed the internet. ChatGPT is the same. Get on the train or get run over. As the AI presentation said, educators have a “responsibility”(!!) to use AI to get better at pedagogy.

Well, I’m okay getting off the train. That’s an option, too, right? We don’t have to ride along if we take a look ahead and see the train is heading off a cliff.

I wouldn’t go so far as Paul Kingsnorth and say that AI is demonic, but I’m certainly not excited about it. In fact, I think AI is uninteresting. If you use AI and think, “Wow, this is cool!” I am probably not going to like you.

Sticking with Wendell Berry

To begin, I have a confession: I have used the new AI technology like ChatGPT. And it’s always for things I don’t care about. Someone wants a summary of something I’ve already written in entirety? I don’t care. ChatGPT can do a fine summary. I did the work already. Or footnotes. I hate footnotes. Plug in a book title and author, tell it to put it in the right style, bingo. I don’t even care if it has the right publisher location or date. On to the next one. What I care least about is posting on social media. I host a podcast, and there’s AI technology that will cut clips based on a “virality rating” for me to upload. (So far, I am still not a viral sensation). If I can find a way to fill out accrediting reports using AI, the destruction of civilization may be worth the cost.

What all of these tasks have in common is that I do not care. AI is good for getting (dumb) things done the fastest and easiest—with the least amount of care or affection. Use it and move on. It’s the ethic of utility and efficiency.

But here’s the problem: the way we treat our life is eventually the way we treat each other. Why do the hard work of friendship when it’s faster and easier to talk to an AI friend? Why begin to love anything if something else can do it better? Why care about learning? It’s easier with AI.

Wendell Berry calls these two modes of living that of a “Boomer” or a “Sticker.”

Boomers are motivated by greed and power. They get into AI early because if they don’t use it, others will, and then they will fall behind. Limits don’t matter. Neighbors don’t matter. Pillage what you can and get ahead. It’s a rat race, and people are out to win.

The thing that distinguishes Stickers from Boomers is affection. Stickers love and care—for their place and for others. They enjoy the tasks they do, so they want to do them. They’re not out to use things and people for their own benefit. They want to see the community flourish—if I use AI to illustrate something, I’m not caring for the graphic designer who would otherwise do this work or the viewers who get the results of a fast, easy process. Lack of care is not victimless.

Human Technology with Thomas Merton

In his Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander, Berry’s fellow Kentuckian Thomas Merton reflects on the pressures of modern life that make us all complicit through inaction. There are no innocent, pure people in modernity. The question is what we do and how we live in our guilt. Or to use another idea from Wendell Berry, we cannot be whole. It’s a broken system. Technology consumes everything. But we can pursue healing and health.

And one way to pursue healing, in Merton’s account, is to relegate technology to its proper place. He writes, “Technology can elevate and improve man’s life only on one condition: that it remains subservient to his real interests; that it respects his true being; that it remembers that the origin and goal of all being is God.” If not, technology “degrades man, despoils the world, ravages life, and leads to ruin.”

Here’s the heart of the matter: does AI serve us, or do we serve it? Do we even know what our real interest, our true being is? In what way does AI serve the origin and goal of our being? Is there any way AI serves wisdom and serves the human? Does it remember the ground of our being is not machine learning but the eternal God?

Berry writes about natural and artificial intelligence. Of a previous age, he says, “We knew, or retained the capacity to learn, that our intelligence could get us into trouble that it could not get us out of. We were intelligent enough to know that our intelligence, like our world, is limited. We seem to have known and feared the possibility of irreparable damage. But beginning in science and engineering, and continuing, by imitation, into other disciplines, we have progressed to the belief that humans are intelligent enough, or soon will be, to transcend all limits and to forestall or correct all bad results of the misuse of intelligence.”

The modern world imagines the human being as an advanced computing processor with no limits. So far, humans have been a more advanced computer. But not for much longer. It seems like we are slowing behind artificial intelligence, so that maybe we should call the computers real intelligence and it’s the human that’s artificial.

But of course, the human being is not a computer. We are not advanced machines. We have limits, which means we have the potential wisdom to know when to say, “enough.” AI does not help me live my human life. I just hope there are enough resistance humans out there to say, “No.”

When our only values are speed, efficiency, and profit, AI makes a lot of sense. Everything can be useful or manufactured. Nothing is discovered or found. All things are curated to you by a machine. AI robs life of giftedness and gratuity because it imagines the human as one without limits.

Cooking with Robert Farrar Capon

One final example of the uninteresting-ness of AI comes from an unlikely source: a book on marriage. In Bed and Board, Robert Farrar Capon discusses the different aspects and commitments of marriage in his playful way. He, as he is wont to do, gets on the subject of food and cooking.

He laments using the “technology” of canned and processed foods rather than cooking with raw ingredients. People who willingly use these ingredients show that they don’t really care for the real things and, therefore, have no love of detail. It comes back to lack of care, to “good enough,” to an absence of affection. It’s faster to buy cans of stewed carrots rather than the hassle of buying them raw, chopping, cooking, etc. Modern cooking relies on more and more fakes. And therefore less and less excellence. As Capon writes, “We are so used to getting the fast result that we have no patience for detail… They love results, but they are unprepared for the fuss required to produce great ones… They are totally unprepared for the fact that it is precisely all that detail that makes the difference.”

The details that make the difference. In a world of boomers, few will be able to tell good from great, manufactured from fresh, human from AI. If you don’t want to discern taste, then don’t. You can live that way. Go for it.

But I can’t. I want to discern greatness, because I care about detail. I want to live as a Sticker, one who cares.

In the AI talk I heard this year, the presenter said that we teachers have a responsibility to use AI to be better teachers. I think that’s terrible advice. It seems we have the responsibility to help students develop their tastes, so that when something, theoretically, comes served from a can, they can tell it’s artificial.

Of course, that means we will need other goals than utility, speed, and profits. It means we will need to train students to care and to love—and to know love pays attention to details and takes time.

And, of course, it means that we, teachers, need to model this affection and love our subjects.

Berry, as usual, is right: It all turns on affection.

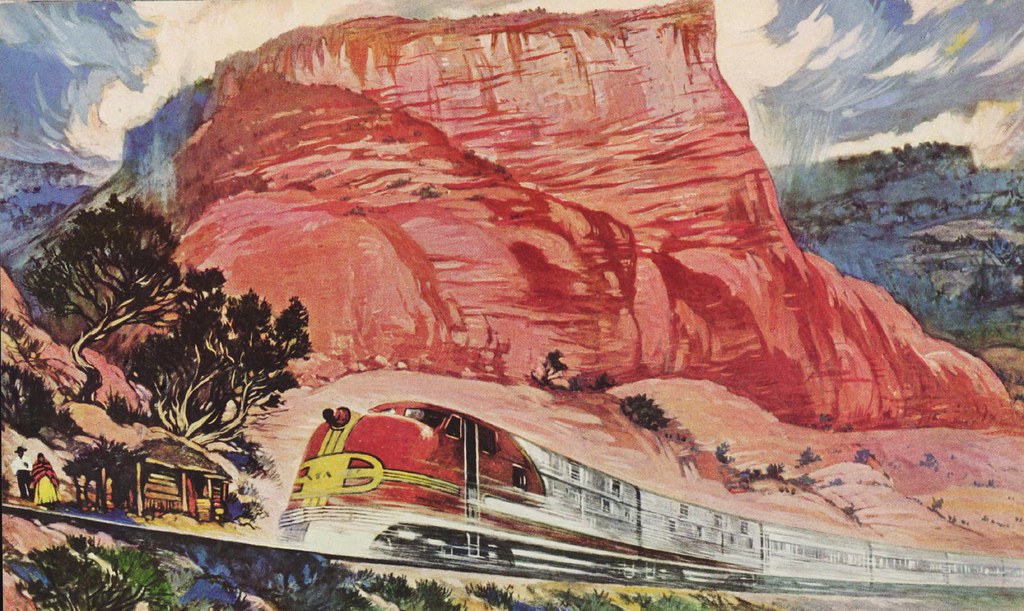

Image Credit: By Thornton Oakley, from the 1943 December issue of National Geographic Magazine. The full collection of illustrations from the 1943 issue may be viewed here.